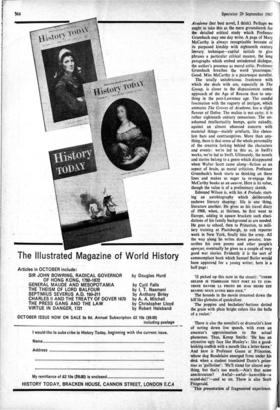

Together again

ANTHONY BURGESS

A Prelude: Landscapes, Characters and Con- versations from the Earlier Years of My Life Edmund Wilson (W. H. Allen 30s) Professor Grumbach tells us biographically what Miss McCarthy has already told us fic- tionally—that marriage with Edmund Wilson wouldn't work and, to some extent, why. Edmund Wilson has only just started on his autobiographical notebooks, of which 'it is un- likely that more than two volumes can appear during the author's lifetime.' Wishing many more fruitful years to Mr Wilson, we cannot hope to hear his side of the story until such time as we may have lost interest. Really, we should not feel interest at all, except that we can learn much about an artist from the way in which he (she in this instance) makes use in art of the raw material of intimate life. Everything else is gossip and scandal.

If we want to know what event helped to spark off the breakdown of the marriage, we can find it in Miss McCarthy's A Charmed Life, in the episode in which the husband is horrid about emptying the garbage pails. But I think it ought to be enough to know that Miss McCarthy has always been the kind of novelist to draw heavily on her own experience—per- haps more than any of her contemporaries (so far as we can judge)—and -that it is no dispar- agement of her imaginative gifts to see her works as commentaries on her life. That she is a genuine novelist, and a very good one, can- not be doubted, but there is something in all her writing that seems to lead us back to the woman herself, not just that creative compart- ment which is locked up when the day's stint is over and it's time to prepare the dinner. I am not interested in Ivy Compton-Burnett or Brigid Brophy or Edna O'Brien, but I am pro- foundly interested in Mary McCarthy.

She has a very interesting mind, and a rather frightening one. In America, before she was launched (with Wilson to push her) as a fiction- writer, she gained the reputation of being one of the sharpest, even cruellest, critics of the day. Professor Grumbach reminds us that Katherine Anne Porter called her 'in some ways the worst-tempered woman in American letters,' and the professor adds: She is the landwrecker McCarthy, like Lord Byron brilliant and, from her targets' point of view, unsound.' Needless to say, there is no evidence of this temper in her private personality; she is charming, aurae- tive,„,kind. But bad writing and sloppy think- ing make her very dangerous. She is rightly mad about style and is herself one of the most dis- tinguished stylists living.

Her novels are strongly individual, but it is hard to summarise their quality. Professor Grumbach doesn't help much; she's more con- cerned with relating The Group to Miss Mc- Cardxy's *assay.- and post-Vassar life and showing us the provesaiace of. The Groves of Academe (her best novel, I think). Perhaps we ought to take this as the mere groundwork for the detailed critical study which Professor Grumbach may one day write. A page of Mary McCarthy is always recognisable because of its purposed kinship with eighteenth century literary technique—capital initials to give phrases a particular critical nuance, the long paragraphs which embed unindented dialogue, the author's presence as moral critic. Professor Grumbach breathes the word `picaresque.' Good. Miss McCarthy is a picaresque novelist.

The totally unlubricious frankness with which she deals with sex, especially in The Group, is closer to the dispassionate comic approach of the Age of Reason than to any- thing in the post-Lawrence age. The candid fascination with the roguery of intrigue, which animates The Groves of Academe, has a slight flavour of Defoe. The malice is not catty; it is rather eighteenth century censorious. The un- ashamed intellectuality bumps, quite nakedly, against an almost obsessed concern with material things—mainly artefacts, like choco- late bars and contraceptives. More than any- thing, there is that sense of the whole personality of the creatrix lurking behind the characters and events: we're led to this as, in Swift's works, we're led to Swift. Ultimately. the novels and stories belong to a genre which disappeared when Walter Scott came along—fiction as an aspect of brain, as moral criticism. Professor Grumbach's book starts us thinking on these lines and makes us eager to re-engage the McCarthy books as an oeuvre. Here is its value, though the value is of a preliminary sketch.

Edmund Wilson is, with his A Prelude, start- ing an autobiography which deliberately eschews literary shaping: life is one thing, literature another. He gives us his travel diary of 1908, when, at thirteen, he first went to Europe, adding in square brackets such eluci- dations of his family background as are needed. He goes to school, then to Princeton, to mili- tary training at Plattsburgh, to cub reporter work in New York, finally into the army. All the way along he writes down pensees, tran- scribes his own poems and other people's apercus; eventually he gives us a couple of very good war stories. Evidently it is the sort of commonplace book which Samuel Butler would have approved for a young writer; here is a half page: `(1 picked up this note in the street): "CHERE HELENE JE TEMBRASSE TOUT FORT ES TU CON- TENTE DAVOIR LA PHOTO DE JEAN HENRI EST REVENU NOUS AVONS BIEN JOVE."

The bounds in the movie streamed down the hill like globules of quicksilver.

The poppies and bachelors'-buttons dotted the grain with plain bright colors like the balls of a rocket.'

There is also the novelist's or dramatist's love of noting down live speech, with even an amateur's approximation to the actual phonemes. Thus, Kemp Smith: `He has an attractive ugly face like Huxley's: like a good- looking codfish with a mouth like a letter-bawx.' And here is Professor Gauss at Princeton, whose dog Baudelaire emerged from under his

desk when a student translated Dante's gelan- lino as `guillotine': `He'll stand for almost any-

thing, but that's too much.—Ain't that some anechronism? Awful—awful—hawrrible---a scand-dal!'—and so on. There is also Scott Fitzgerald.

This presentation of fragmented experience,

dry commentary, scraps of tyro poetry has its own charm: it strikes one as life lived, not life remembered and enhanced by fancy prose trick and unscrupulous editing. Memoirs of Hecate County—one of Wilson's too few fictional works, and a very good one—seemed to show a love of candour for its own sake. This is the essence of good autobiography, as of good criticism: when we read Wilson on other authors we know there'll be no covering up of ignorance, or of erudition either. In the next, maturer, chronicle of his life we can expect an even more interesting nakedness than what shimmers here. This is the real progress of a soul—one of the few souls, in the days when she was excoriating the critics, that Mary McCarthy approved of.

Previous page

Previous page