GREAT BOERS OF TODAY

Samantha Weinberg meets

the man who wants to set up his own tribal homeland

Johannesburg AFTER almost six months on the run — South Africa's most wanted man, the deputy leader of the extremist right-wing Boerestaat Party and self-proclaimed ter- rorist, Piet `Skier (shoot) Rudolph was arrested last week. While Piet Skiet (dub- bed the Boer Pimpernel by the local press), went kicking and screaming to his cell, hissing threats and predicting an instant and bloody demise of the National Party regime, Robert Van Tonder, the leader of the Boerestaat Party, was issuing press statements hailing the erstwhile fugitive as 'a freedom fighter' and a hero.

Since 1977, Van Tonder and Piet Skiet have been perfecting plans for the restora- tion of the old Boer republics as they were before the British united the four states of South Africa into one country in May 1902. While Piet Skiet will undoubtedly — if the current authorities have their way — either be hanged or spend the rest of his life behind bars, Van Tonder is continuing his 'non-violent' crusade for the independence of the Transvaal, Orange Free State and Vryheid by printing pamphlets, writing books and petitioning the United Nations.

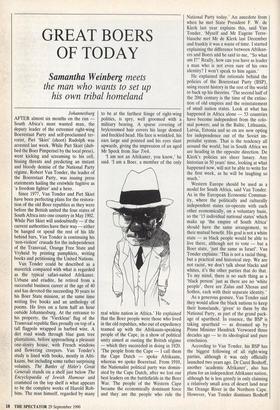

Van Tonder could be described as a maverick compared with what is regarded as the typical safari-suited Afrikaner. Urbane and erudite, he retired from a successful business career at the age of 40 and has devoted the succeeding 30 years to his Boer State mission, at the same time writing five books and an anthology of poems. He lives on a farm half an hour outside Johannesburg. At the entrance to his property, the `Vierkleue flag of the Transvaal republic flies proudly on top of a tall flagpole wrapped in barbed wire. A dirt road winds through blue gum tree plantations, before approaching a pleasant one-storey house, with French windows and flowering creepers. Van Tonder's study is lined with books, mostly in Afri- kaans, but including some rather surprising volumes. The Battles of Hitler's Great Generals stands on a shelf just below The Encyclopaedia of Jewish Humour and crammed on the top shelf is what appears to be the complete works of Harold Rob- bins. The man himself, regarded by many to be at the farthest fringe of right-wing politics, is spry, well groomed with a military bearing. A sparse covering of brylcreemed hair covers his large domed and freckled head. His face is wrinkled, his ears large and pointed and his eyes slant upwards, giving the impression of an aged Mr Spock from Star Trek.

'I am not an Afrikaner, you know,' he said. 'I am a Boer, a member of the only real white nation in Africa.' He explained that the Boer people were those who lived in the old republics, who out of expediency teamed up with the Afrikaans-speaking people of the Cape, in a show of political unity aimed at ousting the British regime — which they succeeded in doing in 1920. 'The people from the Cape — I call them the Cape Dutch — spoke Afrikaans, whereas we spoke Boeretaal. From 1910, the Nationalist political party was domin- ated by the Cape Dutch, after we lost our best leaders on the battlefields in the Boer War. The people of the Western Cape became the economically dominant force and they are the people who rule the National Party today.' An anecdote from when he met State President F. W. de Klerk last year explains this, said Van Tonder. 'Myself and Mr Eugene Terre- blanche met Mr de Klerk last December and frankly it was a waste of time. I started explaining the difference between Afrikan- ers and Boers arid he said to me, "So what am I?" Really, how can you have as leader a man who is not even sure of his own identity? I won't speak to him again.'

He explained the rationale behind the policies of the Boerestaat Party (BSP), using recent history in the rest of the world to back up his theories. 'The second half of the 20th century is the time of the extinc- tion of old empires and the reinstatement of small nation states. Look at what has happened in Africa alone — 53 countries have become independent from the colo- nial powers; and in the Baltic, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia and so on are now opting for independence out of the Soviet im- perialist system. That is the tendency all around the world, but in South Africa we are heading in the opposite direction. De Klerk's policies are sheer lunacy. Any historian in 50 years' time, looking at what happened now, will not be able to write for the first week, as he will be laughing so much.'

Western Europe should be used as a model for South Africa, said Van Tonder.

As in the European Economic Commun- ity, where the politically and culturally independent states co-operate with each other economically, on a voluntary basis, so the '15 individual national states' which make up 'the empire of South Africa' should have the same arrangement, to their mutual benefit. His goal is not a white state — as black people would be able to live there, although not to vote — but a Boer state, 'just the same as Israel'. Van Tonder explains: 'This is not a racial thing, but a practical and historical step. We are not racist, we don't talk about blacks and whites, it's the other parties that do that.

To my mind, there is no such thing as a 'black person' just as there are no 'white people', there are Zulus and Xhosas and Sothos, each with their separate identity.'

As a generous gesture, Van Tonder said they would allow the black nations to keep their homelands, 'given' to them by the National Party, as part of the grand pack- age of apartheid. In essence, the BSP is taking apartheid — as dreamed up by Prime Minister Hendrick Verwoerd three decades ago — to its ideological and pure conclusion.

According to Van Tender, his BSP has the biggest following of all right-wing parties, although it was only officially launched two years ago. Dr Carol Boshoff, another 'academic Afrikaner', also has plans for an independent Afrikaner nation, although he is less greedy in only claiming a relatively small area of desert land near the Orange River in the Northern Cape. However, Van Tonder dismisses Boshoff as 'a bit muddled in his thinking'. 'Most of the right wing accept the fundamental idea of a Boerestaat. My supporters include the ranks of the Afrikaner Weerstandbeweg- ing (AWB), who are of course only a movement, whereas I am a political party,' he said. The BSP would undoubtedly produce candidates to fight a further general election if there is one; however, Van Tonder fears they won't have the opportunity to do so, because of the policies of de Klerk.

Unlike the majority of South Africans, Van Tonder believes the recent violence in this country has a very simple explanation. 'As long as there is an intermingling of 15 different cultures, you will not have peace. What you see now is the Zulus fighting the Xhosas, a natural occurrence that has been going on in Africa for centuries. And it is going to escalate because de Klerk has taken the lid off [by unbanning political organisations and entering into negotia- tions] and created expectations he cannot hope to fulfill. He can't suddenly wave a magic wand and call everyone "South Africans"; there is no such thing as a South African culture, it's a load of hooey. He doesn't seem to realise that he is dealing with separate yolk. De Klerk and Mandela want to perpetuate the mistakes of history, made by British imperialists who tried to bundle different nations together. It will never work.'

So what does Van Tonder see in his glass ball? 'Utter failure. If it keeps on going like this, we are going to slide into anarchy, backwardness, a third world situation where there is bankruptcy, fighting and corruption.' Eventually the Boerestaat will emerge out of the 'mess-up' and come into being. 'The Boere will take over and very little force will be necessary,' according to the wisdom of Van Tonder.

He is prepared to fight to the bitter end. 'I've no option,' he admitted. (In an earlier interview, however, he said that if the ANC did indeed accede to power, he had one request. 'All I ask of Mr Mandela is that when he puts me in prison, he gives me the cell he had. You know, the one with the pool and garden.') While most of the whites would probably flee if it did come to a fight, the ones that stayed would not be taken easily. 'We all have guns and we will use them. That is one good thing the government has done: they have trained all our people in the army. I have five sons and every one of them is fighting fit. All we have to do is to organise the people. The BSP has an agreement with the Boere Weerstand- beweging [often described as the military wing of the BSP], who are very well trained militarily. They know what to do. We are organising on the ground, but being quiet about it. We are not in the terrorist game.'

The Boerestaat Party is not taken too seriously by the political mainstream in South Africa. Van Tonder himself is re- spected as one of the only politicians in this country who has at least held steadfastly to his views, which, however, are regarded as slightly loony in the current mood of `pretoriastroikee , although they might have been in the mainstream only 30 years ago. Still, sympathy is undoubtedly growing for the idea of a white — if not Boer — homeland, insulated from the spreading black township violence, and white views are polarising with, it is suspected, more defecting to the Right than to the Left.

Van Tonder at least is confident that in the long run, say within 20 years, South Africa has a 'very, very bright future', with the nation states co-operating happily with each other. As I left, he shook my hand and said I would be very welcome in the Boerestaat one day. But would I qualify? He laughed. 'I had an English grand- mother and they make very good Boere, I don't see why you wouldn't.' As I drove away, feeling puzzled, I wondered if he had heard my name correctly.

Previous page

Previous page