BOOKS

Secreted in White's

Hugh Trevor-Roper

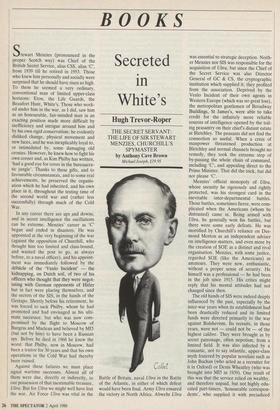

THE SECRET SERVANT: THE LIFE OF SIR STEWART MENZIES, CHURCHILL'S SPYMASTER by Anthony Cave Brown

Michael Joseph, £19.95

Stewart Menzies (pronounced in the proper Scotch way) was Chief of the British Secret Service, alias CSS, alias 'C', from 1939 till he retired in 1953. Those who knew him personally and socially were surprised that he should have risen so high. To them he seemed a very ordinary, conventional man of limited upper-class horizons: Eton, the Life Guards, the Beaufort Hunt, White's. Those who work- ed under him in the war, as I did, saw him as an honourable, fair-minded man in an exacting position made more difficult by inefficiency and intrigue around him and by his own rigid conservatism: he evidently disliked change, physical movement and new faces, and he was inexplicably loyal to, or intimidated by, some damaging old cronies. However, he knew how to fight his own corner and, as Kim Philby has written, 'had a good eye for cover in the bureaucra- tic jungle'. Thanks to these gifts, and to favourable circumstances, and to some real achievements, he preserved the organis- ation which he had inherited, and his own place in it, throughout the testing time of the second world war and (rather less successfully) through much of the Cold War.

In any career there are ups and downs, and in secret intelligence the oscillations can be extreme. Menzies' career as 'C' began and ended in disasters. He was appointed at the very beginning of the war (against the opposition of Churchill, who thought him too limited and class-bound, and wanted the post to go, as always before, to a naval officer), and his appoint- ment was immediately followed by the &bade of the 'Venlo Incident' — the kidnapping, on Dutch soil, of two of his officers who thought that they were negot- iating with German opponents of Hitler but in fact were placing themselves, and the secrets of the SIS, in the hands of the Gestapo. Shortly before his retirement, he was forced to sack Philby, whom he had promoted and had envisaged as his ulti- mate successor, but who was now com- promised by the flight to Moscow of Burgess and Maclean and believed by MI5 (but not by him) to have been a Russian spy. Before he died in 1968 he knew the worst: that Philby, now in Moscow, had been a traitor for 30 years and that his own operations in the Cold War had thereby been ruined.

Against these failures we must place signal wartime successes. Almost all of them were due, directly or indirectly, to our possession of that inestimable treasure, Ultra. But for Ultra we might well have lost the war. Air Force Ultra was vital in the Battle of Britain, naval Ultra in the Battle of the Atlantic, in either of which defeat would have been final. Army Ultra ensured the victory in North Africa. Abwehr Ultra was essential to strategic deception. Neith- er Menzies nor SIS was responsible for the acquisition of Ultra, but since the Chief of the Secret Service was also Director General of GC & CS, the cryptographic institution which supplied it, they profited from the association. Deprived by the Venlo Incident of their own agents in Western Europe (which was no great loss), the metropolitan gentlemen of Broadway Buildings, St James's, were able to take credit for the infinitely more reliable sources of intelligence opened by the toil- ing peasantry on their chief's distant estate at Bletchley. The peasants did not find the connection so useful. When a crisis of manpower threatened production at Bletchley and normal channels brought no remedy, they took the extreme step of by-passing the whole chain of command, including 'C', and appealing direct to the Prime Minister. That did the trick, but did not please 'C'.

Menzies' official monopoly of Ultra, whose security he rigorously and rightly protected, was his strongest card in the inevitable inter-departmental battles. Those battles, sometimes fierce, were com- plicated when the Americans (whom he distrusted) came in. Being armed with Ultra, he generally won his battles, but there were some early defeats. He was mortified by Churchill's reliance on Des- mond Morton as an independent adviser on intelligence matters, and even more by the creation of SOE as a distinct and rival organisation. Menzies, with some justice, regarded SOE (like the Americans) as amateurs. They were new, enthusiastic, without a proper sense of security. He himself was a professional — he had been in the job since 1915. His critics might reply that his mental attitudes had not changed since then.

The old hands of SIS were indeed deeply influenced by the past, especially by the inter-war years when its establishment had been drastically reduced and its limited funds were directed primarily to the war against Bolshevism. Its recruits, in those years, were not — could not be — of the highest calibre. They were brought in by secret patronage, often nepotism, from a limited field. It was also infected by a romantic, not to say infantile, upper-class myth fostered by popular novelists such as John Buchan (who acted as a recruiter for it in Oxford) or Denis Wheatley (who was brought into MI5 in 1939). One result of this was that the service relied on wealthy, and therefore unpaid, but not highly edu- cated part-timers, 'honourable correspon- dents', who supplied it with prejudiced gossip from aristocratic houses in Europe. I have known some of these people; they often end by living in a world of fantasy an occupational hazard. Deciphered mate- rial, of course, was different: it was still supplied by the old experts of the first world war; but the vital Russian 'decrypts' were lost when they were cited in Parlia- ment to justify the 'Arcos Raid' of 1927. The Russians then naturally changed their ciphers. In consequence, SIS retained a justified suspicion of all politicians. Like SOE and Americans they were held to be congenitally insecure.

These conditions help to explain the defects of SIS in 1939 — defects which neither Menzies nor any of his colleagues were eager to reform. The pressure came from outside, from the Services and from the Foreign Office. The Services contrived to insert 'commissars' into SIS as Deputy Directors. They did not achieve much. The Foreign Office seconded one of its mem- bers as a personal assistant to 'C'. The new assistant was appalled by the disorder and the atmosphere of prejudice and intrigue which he found there. Menzies' over- powering deputy, he discovered, was 'the most evil and most wicked man I had met in public service.' Some rational changes of procedure were introduced, but a real structural change was not to be achieved at that level, or at that time, or with those persons. It had to await a new generation.

Late in his life, shaken by the Philby affair, Menzies wrote his 'recollections'. These have been described to me, by a well-qualified friend who read them, as `self-glorifying fantasy'. They have been used by Mr Cave Brown, who has also had personal information from the Menzies family. His biography, which is written on the American model, bringing in every- thing, sometimes twice over, dwells with goggle-eyed relish on the Edwardian world of wealth and privilege in which his hero's life was enclosed: but he has also worked industriously, through public and private sources, both here and in America. He is particularly interesting on the relations between SIS and the Americans, especially William J. Donovan's OSS. Some of his statements seem to me rash, and some I know to be untrue, but the book is documented and full of information: a good, if a very long, read.

My main criticism is that Mr Cave Brown writes as if SIS was the sole source and interpreter of secret intelligence, and credits to 'C' personally decisions and actions for which his responsibility was very limited: he had been a channel of communication, or a member of the approving committee, or had seen the papers. In fact the function of SIS was to collect intelligence by secret means: it neither interpreted it, nor formulated poli- cy, nor (except to obtain it) took action. Mr Cave Brown's references are copious but often fail us when they are most needed. Some of his suggestions seem to me very wild. I know of neither evidence nor probability for the theory that 'C' organised the murder of either Admiral Darlan in Algiers or Reinhardt Heydrich in Prague, and the motive which he offers for the latter murder is absurd. So are the arguments by which he would like to persuade himself that 'C' knew all along that Philby was a Russian spy and used him as a double agent, thus deceiving his own colleagues and allies. This would make his hero more of a traitor than his villain.

`C' was not a super-spy or a brilliant `spy-master'; but if the public mythology needs someone in that role, he is more deserving than the dreadful Claude Dansey or the egregious William Stephenson, who have already been so honoured; and this biography gives some flesh and a little (off-blue) blood to the sedentary, with- drawn, overworked, unimaginative secret bureaucrat who concealed his work and his personality behind the green light outside his office in Broadway Buildings, the green ink of his laconic official ideogram, and the protective doors of his private citadel, White's.

Previous page

Previous page