Mind We Don't Quarrel

BY KINGSLEY AMIS WHEN I got there the party of demonstrators consisted of three women and a baby. One of the women was the wife of B., a prominent Swansea businessman and benefactor, and another was the wife of a colleague of mine at the University College. The third woman was my wife and the baby was my baby—two in January, actually, and very mobile indeed. As well as being more personal, the baby's demonstrations of protest were also incomparably more vigor- ous than anybody else's that afternoon.

At this early stage. however, all was quiet. Policemen walked reflectively to and fro in the roadway between the steps of the Guildhall and the large circular stretch of pavement where we stood. Law-abiding to the backbone, we kept off the grass-plot behind us and refrained from doing or saying anything likely to cause a breach of anything. More policemen were hanging about the portals of the building, ready for the emergence of the great man at present lunching inside with the Mayor, a necessary recruitment, no doubt, after the toil of opening the new Fire Station in the morning and before being inaugurated as President of the University College of Swansea in the after- noon. The top brass of the police force was represented by a big, fat man with a major's badges of rank—Inspector? Chief Inspector? Superintendent? He gave us a look from which interest and cordiality were alike absent.

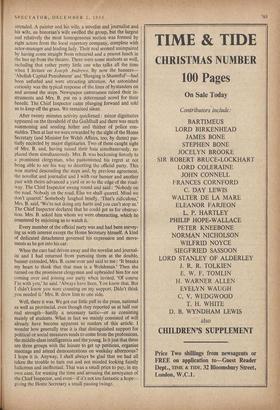

Our numbers began to be augmented. A philosopher arrived with his wife and small child, then another philosopher un- attended. A painter and his wife, a novelist and journalist and his wife, an historian's wife swelled the group, but the largest and relatively the most homogeneous section was formed by eight actors from the local repertory company, complete with actor-manager and leading lady. Their zeal seemed unimpaired by having come straight from rehearsal and a peanut lunch in the bus up from the theatre. There were some students as well, including that rather pretty little one who talks all the time when I lecture on Joseph Andrews, By now the banners— `Abolish Capital Punishment' and 'Hanging is Shameful'—had been unfurled and were attracting attention. An astonished curiosity was the typical response of the lines of bystanders on and around the steps. Newspaper cameramen raised their in- struments and Mrs. B. put on a determined scowl for their benefit. The Chief Inspector came plunging forward and told us to keep off the grass. We remained silent.

After twenty minutes activity quickened : minor dignitaries appeared on the threshold of the Guildhall and there was much summoning and sending hither and thither of police con- stables. Then at last we were rewarded by the sight of the Home Secretary (and Minister for Welsh Affairs, too, by damn) par- tially encircled by major dignitaries. Two of these caught sight of Mrs. B. and, having raised their hats simultaneously. re- placed them simultaneously. Mrs. B. was beckoning fiercely to a prominent clergyman, who pantomimed his regret at not being able to see his way to deserting the official party. This now started descending the steps and, by previous agreement, the novelist and journalist and I with our banner and another pair with theirs advanced a yard or so to the edge of the road- way. The Chief Inspector swung round and said : 'Nobody on the road. Nobody on the road. Else we shall quarrel. Mind we don't quarrel.' Somebody laughed briefly. 'That's ridiculous.' Mrs. B. said. 'We're not doing any harm and you can't stop us.' The Chief Inspector declared that he could get us for obstruc- tion. Mrs. B. asked him whom we were obstructing, which, he countered by enjoining us to watch it.

Every member of the official party was and had been survey- ing us with interest except the Home Secretary himself. A kind of dedicated detachment governed his expression and move- ments as he got into his car.

When the cars had driven away and the novelist and journal- ist and I had returned from pursuing them at the double, banner extended, Mrs. B. came over and said to me : 'It breaks my heart to think that that man is a Welshman.' Then she turned on the prominent clergyman and upbraided him for not coming over and joining our party when invited. 'Of course -in with you,' he said. 'Always have been. You know that. But 1 didn't know you were counting on my support. Didn't think you needed it.' Mrs. B. drew him to one side.

Well, there it was. We got our little puff in the press, national as well as provincial, even though they reported us at half our real strength—hardly a necessary tactic—or as consisting mainly of students. What in fact we mainly consisted of will already have become apparent to readers of this article. I wonder how generally true it is that distinguished support for political or social measures tends to come from the professions, the middle-class intelligentsia and the young. Is it just that these are three groups with the leisure to get up petitions, organise meetings and attend demonstrations on weekday afternoons? I hope it is. Anyway, I shall always be glad that we had all taken the trouble to turn out and not minded looking faintly ludicrous and ineffectual. That was a small price to pay, in my own case, for wasting the time and arousing the annoyance of the Chief Inspector, and even—if it's not too fantastic a hope-- i ng the Home Secretary a small passing twinge.

Previous page

Previous page