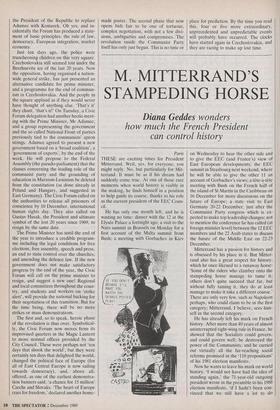

M. MITTERRAND'S STAMPEDING HORSE

Diana Geddes wonders

how much the French President can control history

Paris THESE are exciting times for President Mitterrand. Well, yes, for everyone, you might reply. No, but particularly for Mit- terrand. It must be as if his dream had suddenly come true. At one of those rare moments when world history is visibly in the making, he finds himself in a position to help guide its course, thanks to his role as the current president of the EEC Coun- cil.

He has only one month left, and he is wasting no time: dinner with the 12 at the Elysee Palace a fortnight ago; a visit to the Nato summit in Brussels on Monday for a first account of the Malta summit from Bush; a meeting with Gorbachev in Kiev on Wednesday to hear the other side and to give the EEC (and France's) view of East European developments; the EEC summit in Strasbourg next weekend, where he will be able to give the other 11 an account of Gorbachev's views; a tete-a-tete meeting with Bush on the French half of the island of St Martin in the Caribbean on 16 December for more discussions on the future of Europe; a state visit to East Germany 20-22 December, just after the Communist Party congress which is ex- pected to make top leadership changes; not to mention the conference he has called (at foreign minister level) between the 12 EEC members and the 22 Arab states to discuss the future of the Middle East on 22-23 December.

Mitterrand has a passion for history and is obsessed by his place in it. But Mitter- rand also has a great respect for history, which he once likened to a runaway horse: 'Some of the riders who clamber onto the stampeding horse manage to tame it; others don't quite succeed that far, but without fully taming it, they do at least manage to make it take a different course.' There are only very few, such as Napoleon perhaps, who could claim to be in the first category; Mitterrand, I believe, sees him- self in the second category.

He has already left his mark on French history. After more than 40 years of almost uninterrupted right-wing rule in France, he showed that the Socialists could govern, and could govern well; he destroyed the power of the Communists; and he carried out virtually all the far-reaching social reforms promised in the '110 propositions' of his 1981 election manifesto.

Now he wants to leave his mark on world history. 'I would not have had the idea of standing again,' the 71-year-old outgoing president wrote in the preamble to his 1988 election manifesto, 'if I hadn't been con- vinced that we still have a lot to do together to ensure for our country the role that is expected of it in the world and to guard over the unity of the nation.'

Like de Gaulle, Mitterrand is an ardent patriot. Like de Gaulle too, 'M. Mitter- rand wants to give us the image of a man, alone, infallible, united to the "sovereign people" of his country,' as Jacques Amal- ric, Le Monde's diplomatic editor, wrote in a review of a collection of Mitterrand foreign policy speeches, published in 1986. But unlike de Gaulle, Mitterrand no longer has a vision of France 'going it alone'.

Mitterrand is very sensitive about the dominating, not to say crushing, influence of the United States and the USSR over the last half century. In the preface to his book on foreign policy he wrote, in 1986:

At Teheran in 1943 and again in Yalta in 1945, Western Europe was absent from world affairs, despite Churchill. It only existed in the negative, as the tilting-ground of the Russo-American confrontation, and only preserving its fragile stability through that confrontation. Re-awakened today, it has not the means — because it did not want them — to realise the dream which would give it reality, identity and power.

Mitterrand is determined to give Europe those means, whether all 12 members want it or not. It was partly to show that Europe was capable of discussing its own destiny that he decided to summon the Twelve — ahead of the Strasbourg summit — to discuss developments in Eastern Europe before Bush and Gorbachev had a chance to decide everything between themselves at their summit this weekend.

Asked after the Flys& dinner on 18 November whether he would go to Malta to give an account of their conversation to the two leaders, he replied with typical French prickliness, 'Can you imagine me going to a boat in the middle of the Mediterranean to give an account of our discussions among the Twelve, and then leaving the two superpowers alone to discuss the affairs of the world?' That was precisely the kind of thing that had been going on for the past 40 years, he said, adding, 'Let us hope that one day such summits will take place a trois!'

In the meantime, separate meetings have been arranged between him and the two superpower leaders, thereby preserv- ing European (and French) dignity. But it is not just a question of pride and dignity. As Mitterrand has made clear in two important interviews (with the Wall Street Journal and Paris-Match) over the past fortnight, he believes that Europe is at a dangerous crossroads. 'At present, history could go one way or the other. We just don't know which way it is going to go,' he said.

It was good that Europe was emerging peacefully from the order established after the last world war. However, then at least, Europe had had stability. 'It was an armed peace, but nevertheless peace,' he said. 'We knew that stability. We had got used to it. Now we've got to invent another. But before succeeding, Europe will go through a period of turbulence and crisis. We will need imagination and sang-froid. In short, the difficulties are beginning.'

Mitterrand's genuine anxiety, but also his excitement, shines through both inter- views. He says he fears for Gorbachev's future, not simply because of the pace of developments in the Eastern bloc, but also because of the disastrous decline of the Soviet economy: 'It cannot but get worse. They're on the brink of disaster. And the paradox is that only the West can prevent Russia from falling over the brink.'

Although Mitterrand continues to insist that he personally does not fear German reunification (few believe him), he says that it could be very dangerous for Gor- bachev given Russia's strategic, geopolitic- al and historical interests in preserving the existing borders. It could also start a chain reaction in other Eastern bloc countries and produce a resurgence of old rivalries such as those between Germany and Po- land over Pomerania, between Serbia and Croatia over Montenegro, and between Hungary and Rumania over Transylvania. The march of liberty was to be applauded, he said, but peace also needed to be safeguarded.

He went on to re-emphasise the import- ance of forcing the pace of Western Euro- pean integration. 'Europe of,the Commun- ity is the only pole of attraction possible for people in search of unity and democracy,' he said. 'I hope that the Western European countries will (now) be all the more con- scious of the urgency for them to complete the work of the Community. "Move fas- ter!" That's what I am asking them, otherwise they will be swept away in the maelstrom . . . We are going to go through a period of great tension. In the immediate landscape, I see only one bridge within reach: the European Community. Let us make haste to strengthen its foundations and accelerate its construction!'

The dramatic developments in Eastern Europe could not have happened at a better time for Mitterrand. Not only will they lend éclat to what had threatened to be a very dull and routine EEC presidency for the French (no immediate crises to be solved; no major initiatives to be taken), but they will also help strengthen his hand in his confrontation with Mrs Thatcher at the EEC summit in Strasbourg next week over European economic and monetary union (EMU) and the social charter. Unlike Mrs Thatcher, Mitterrand be- lieves that both EMU and the social charter are indispensable stepping-stones to the realisation of his ultimate goal — the creation of a united political Europe, in which France continues to play a leading role. For that reason, the vision of a greater Europe 'from the Atlantic to the Urals' does not attract Mitterrand (though he pays lip-service to it.) While he claims he does not want to create a 'two-speed' Europe, he nevertheless insists that coun- tries (like Britain) in the tail of the train should not be allowed to brake countries (such as France) in the locomotive. The threat is clear.

Mitterrand has always had a passion for foreign policy. He devours history books; he collects maps of the world. As a young deputy at the end of the Forties and in the early Fifties, he was already talking ardent- ly about the need for the construction of a united Europe and the importance of creating a Paris-Bonn axis. As leader of the Socialist Party, in opposition he made a point of touring the globe and meeting foreign heads of state and government; and during his past eight and a half years as president his penchant for foreign travel has by no means diminished. There is no other European leader with his depth and breadth of experience in world affairs. But for how long will France be able to steer the stampeding horse once its EEC pres- idency comes to an end on 31 December?

Previous page

Previous page