DEVELOPING CHARITY

Dominic Lawson meets Godfrey Bradman

a man who has done well, and is doing good

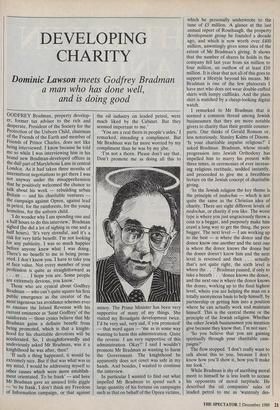

GODFREY Bradman, property develop- er, former tax adviser to the rich and desperate, President of the Society for the Protection of the Unborn Child, chairman of the Friends of the Earth and member of Friends of Prince Charles, does not like being interviewed. I know because he told me so while I was interviewing him in his brand new Bradman-developed offices in the dull part of Marylebone Lane in central London. As it had taken three months of intermittent negotiations to get there I was not anyway under the misapprehension that he positively welcomed the chance to talk about his work — rebuilding urban Britain — and his charitable ventures the campaign against Opren, against lead in petrol, for the rainforests, for the young homeless, for the unborn child.

`I do wonder why I am spending one and a half hours to do this interview,' Bradman sighed (he did a lot of sighing in one and a half hours). 'It's very stressful, and it's a risk for very little benefit. I'm not looking for any publicity. I was so much happier before anyone knew what I was doing. There's no benefit to me in being prom- oted. I don't know you. I have to take you at face value. Not every member of your profession is quite as straightforward as • er . . I hope you are. Some people are extremely devious, you know.' Those who are cynical about Godfrey Bradman — who can't quite square his first public emergence as the creator of the most ingenious tax avoidance schemes ever to ensnare the Inland Revenue with his current eminence as 'Saint Godfrey' of the rainforests — those cynics believe that Mr Bradman gains a definite benefit from being promoted, which is that a knight- hood for his charitable devotions will be accelerated. So, I straightforwardly and undeviously asked Mr Bradman, was it a knighthood he was after, then?

`If such a thing happened, it would be extremely nice. But if that was what was in my mind, I would be addressing myself to other causes which were more establish- ment orientated. To be frank' — and here Mr Bradman gave an amused little giggle — 'to be frank, I don't think my Freedom of Information campaign, or that against the oil industry on leaded petrol, were much liked by the Cabinet. But they seemed important to me.'

`You are a real thorn in people's sides,' I remarked, intending a compliment. But Mr Bradman was far more worried by my compliment than he was by my jibe.

`I'm not a thorn. Please don't say that. Don't promote me as doing all this to annoy. The Prime Minister has been very supportive of many of my things. She visited my Broadgate development twice. I'd be very sad, very sad, if you promoted' — that word again — 'me as in some way wanting to harm this administration. Quite the reverse. I am very supportive of this administration. Okay?' I said I wouldn't promote Mr Bradman as wanting to harm the Government. The knighthood he apparently does not covet was safe in my hands. And besides, I wanted to continue the interview.

In particular I wanted to find out what impelled Mr Bradman to spend such a large quantity of his fortune on campaigns such as that on behalf of the Opren victims, which he personally underwrote to the tune of £5 million. A glance at the last annual report of Rosehaugh, the property development group he founded a decade ago, and which is now worth over £400 million, unwittingly gives some idea of the extent of Mr Bradman's giving. It shows that the number of shares he holds in the company fell last year from six million to four million, an outflow of at least £10 million. It is clear that not all of this goes to support a lifestyle beyond his means. Mr Bradman is one of the few plutocrats I have met who does not wear double-cuffed shirts with lumpy cufflinks. And the plain shirt is matched by a cheap-looking digital watch.

I remarked to Mr Bradman that it seemed a common thread among Jewish businessmen that they are more notable givers to charity than their gentile counter- parts. One thinks of Gerald Ronson or, less notoriously, Stanley Kalms of Dixons. `Is your charitable impulse religious?' I asked Bradman. Bradman, whose steady progression into Jewish Orthodoxy has impelled him to marry his present wife three times, in ceremonies of ever increas- ing religious rectitude, nodded instantly, and proceeded to give me a breathless lecture on the Jewish concept of charitable giving.

`In the Jewish religion the key theme is the principle of tsedochas — which is not quite the same as the Christian idea of charity. There are eight different levels of tsedochas, or charity if you like. The worst type is where you just ungraciously throw a coin to a beggar, and purposely make him crawl a long way to get the thing, the poor bugger. The next level — I am working up to the best — is where the donor and the donee know one another and the next one is where the donor knows the donee but the donee doesn't know him and the next level is reversed and then . . . actually that's not quite right, the sixth level is where the . . .' Bradman paused, if only to take a breath . . . 'donee knows the donor, and the next one is where the donor knows the donee, working up to the final highest level, where you are helping the man on a totally anonymous basis to help himself, by partnership or getting him into a position where he can actually work and maintain himself. This is the central theme or the principle of the Jewish religion. Whether the other Jewish businessmen you mention give because they know that, I'm not sure.'

`So you believe that you are gaining spiritually through your charitable cam- paigns?'

The flow stopped. 'I don't really want to talk about this to you, because I don't know how you'll show it, how you'll make me look.'

While Bradman is shy of ascribing moral merit to himself he is less loath to accuse his opponents of moral turpitude. He described the oil companies' sales of leaded petrol to me as 'wantonly des- troying the intellects of our children — it was a terrible sin they were committing.'

But the religious impulse can explain only the extent of Bradman's giving. It does not fully explain its direction. And here something much more human emerges: that the man gets enormous pleasure from the intellectual challenge of taking on and defeating mighty vested interests, such as the oil and pharmaceutic- al industries.

`I had a lot of fun being involved in the lead in petrol campaign,' Bradman said to me, and then, a few minutes later, 'I had a lot of fun with the Opren victims cam- paign.' Fun seemed a strange word in that grim context, but Bradman did not enjoy me saying that. 'Maybe,' he replied, 'you are one of those people who believe that you can't do anything good if you're enjoying it.' I said I was not that sort of person. said Mr Bradman.

Mr Bradman first discovered how to `have fun' with money in February 1974, when he offered to pay the National Union of Mineworkers £2.5 million, in an effort to bring an end to the debilitating miners' strike. I was amazed at the recall of the precise figures Mr Bradman had, when I reminded him of this 17-year-old episode. `Scargill said that he would reconvene the National Executive of the union and go back to work if he had £3 per man per week for 30 days. That was £80,000 per day for a month. That's where you got that figure of £2.5 million from. In the event Scargill wasn't interested in a settlement.' A few months later, in May 1974, an anonymous donor settled the engineering union's £65,000 debt to the Industrial Relations Court, and thus averted a national strike. Mr Bradman, I surmise, was rising up the tsedochas scale. This time the donee did not know the donor. . . .

It was at about this time, as Denis Healey began to carry out his promise to squeeze the rich until the pips squeaked, that Mr Bradman made his first fortune, as Britain's foremost tax accountant and de- signer of amazingly complex offshore tax avoidance schemes which were defeated only by Acts of Parliament specifically designed to render them illegal. An article of this period described Bradman as a `director of 120 companies', with names such as 'Copfree Investment', 'Swordfish Dealing' and `Kompound Investment'. One of his more bizarre schemes passed even the scrutiny of the Law Lords. There was a marvellous moment in that hearing (in 1980) when Lord Justice Templeman attempted to describe Mr Bradman's tax avoidance scheme involving five shell property companies called A, B, C, F and S: The effect of the scheme was to create rights and liabilities in order that they might be destroyed. The 999-year leases were created and destroyed in six days and in 11 days the duties to pay and the rights to receive instalments of purchase price and premiums

were devoured by Mr Bradman's companies, a faithful and well-trained pack of hounds. He had laid his pack on the trail of a non-existent fox; the properties used for the drag to provide the scent were taken out by ABCFS and returned to Central; at the end of the day the hounds were secure in their kennels and nothing remained save the Revenue's broken hedges and the entries of Mr Jorrocks in the books and records of the hunt.

I was strangely reminded of this ornate business structure when Bradman de- scribed to me his Rosehaugh Self-Build scheme, which is designed to provide a self-financing package enabling homeless or poor people to build and then buy their own homes. `Do you know how it's done? You set up a self-building housing associa- tion. It gets a lease with rights of conver- sion to freehold. The landowners get a yield of 2.5 per cent above the Retail Price Index, as a rent paid to the Self-Building Housing Association which by that stage has converted to co-ownership; they pay interest on a MIRAS Building Society Loan and the freeholder either gets a lump sum when they buy or alternatively gets a stream of rent in years to come. So everyone is very nicely balanced.'

`You thought this all up by yourself?'

`Yes. Over lunch with the Prince of Wales, in fact. He asked me for some way to provide homes for those who cannot afford it, and I drew this scheme as we sat there . . . it was like a spark from heaven. Only it then took one and a half years to get the scheme past nine different govern- ment departments, four firms of lawyers and two firms of consultant actuaries.' I suggested to Mr Bradman that there was a certain symmetry between his days in the shady world of tax avoidance and his present as an originator of schemes to house the homeless: that in both cases he was using to the full his extraordinarily creative business mind, first for the rich, and now for the poor. Mr Bradman was not happy with this parallel, agitatedly picking at the pages of a company brochure as I made it.

`Nothing that I ever did was shady, and I don't want this self-build thing demeaned by such comparisons. . . My time as a tax adviser was an enormous waste of my talents. I thought you were going to ask me questions about Rosehaugh. It's my pride and joy.'

And at this point Mr Bradman turned the Rosehaugh company brochure towards me, flicking lovingly through its lush colour photographs of all his developments, past (Broadgate), present (Holborn Viaduct) and future (King's Cross). 'Look at these,' he implored, and I began to feel like a heel, like a man who is invited round to his neighbour's house, refuses to ask him about his holiday, and then looks the other way when the slides are shown.

But when the time came to leave (that is, when Mr Bradman let out a sigh of seismic proportions and said, 'I haven't got the strength to answer another question'), the chairman of Rosehaugh behaved like the perfect host: he escorted me through all the corridors and down all the floors of `guaranteed' non-rainforest wood panell- ing, and waved goodbye at his front door. Only he didn't say, 'Come again soon.

`Yes, this is the Macdonald farm — What? You'll have to speak up. . .

Previous page

Previous page