ARTS

Art

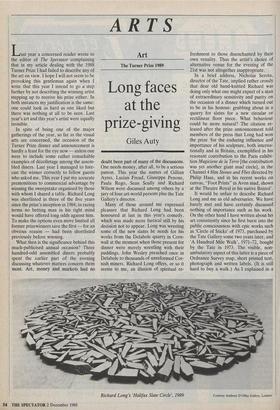

The Turner Prize 1989

Long faces at the prize-giving

Giles Auty

Last year a concerned reader wrote to the editor of The Spectator complaining that in my article dealing with the 1988 Turner Prize I had failed to describe any of the art on view. I hope I will not seem to be provoking this gentleman again when I write that this year I intend to go a step further by not describing the winning artist stepping up to receive his prize either. In both instances my justification is the same: one could look as hard as one liked but there was nothing at all to be seen. Last year's art and this year's artist were equally invisible.

In spite of being one of the major gatherings of the year, so far as the visual arts are concerned, the occasion of the Turner Prize dinner and announcement is hardly a feast for the eye now — unless one were to include some rather remarkable examples of decolletage among the assem- bled diners. Last year I managed to fore- cast the winner correctly to fellow guests who asked me. This year I put my accurate premonitions to commercial advantage by winning the sweepstake organised by those with whom I shared a table. Richard Long was shortlisted in three of the five years since the prize's inception in 1984; in racing terms no betting man in his right mind would have offered long odds against him. To make the options even more limited all former prizewinners save the first — for an obvious reason — had been shortlisted previously before winning.

What then is the significance behind this much-publicised annual occasion? Three hundred-odd assembled diners probably spent the earlier part of the evening discussing whatever matters concern them most. Art, money and markets had no doubt been part of many of the discussions. One needs money, after all, to be a serious patron. This year the names of Gillian Ayres, Lucian Freud, Giuseppe Penone, Paula Rego, Sean Scully and Richard Wilson were discussed among others by a jury of four art-world persons plus the Tate Gallery's director.

Many of those around me expressed pleasure that Richard Long had been honoured at last in this year's comedy, which was made more farcical still by his decision not to appear. Long was wresting some of the new slates he needs for his works from the Delabole quarry in Corn- wall at the moment when those present for dinner were merely wrestling with their puddings. John Wesley preached once in Delabole to thousands of unreformed Cor- nish miners. Richard Long offers, or so it seems to me, an illusion of spiritual re- freshment to those disenchanted by their own venality. Thus the artist's choice of alternative venue for the evening of the 21st was not altogether inappropriate.

In a brief address, Nicholas Scrota, director of the Tate, implied rather crossly that dear old hand-knitted Richard was doing only what one might expect of a man of extraordinary sensitivity and purity on the occasion of a dinner which turned out to be in his honour: grubbing about in a quarry for slates for a new circular or rectilinear floor piece. What behaviour could be more natural? The citation re- leased after the prize announcement told members of the press that Long had won the prize 'for the enduring influence and importance of his sculpture, both interna- tionally and in Britain, exemplified in his resonant contribution to the Paris exhibi- tion Magiciens de la Terre [the contribution was yet another giant mud circle], in the Channel 4 film Stones and Flies directed by Philip Haas, and in his recent works on canvas, "Foot Prints" in Avon mud, shown at the Theatre Royal in his native Bristol'.

It would be unfair to describe Richard Long and me as old adversaries. We have barely met and have certainly discussed nothing of importance such as his work. On the other hand I have written about his art consistently since he first burst into the public consciousness with epic works such as 'Circle of Sticks' of 1973, purchased by the Tate Gallery some two years later, and `A Hundred Mile Walk', 1971-72, bought by the Tate in 1973. The visible, non- ambulatory aspect of this latter is a piece of Ordnance Survey map, short printed text, photograph and written labels. (It is still hard to buy a walk.) As I explained in a Richard Long's 'Halifax Slate Circle', 1989

Courtesy Anthony D'Offay Gallery, London

book I wrote at the time: `... in the world of the visual arts, attempts to extend frontiers have often resulted in nothing more than an artist exchanging a minor talent in one field for an insignificant proficiency in another.'

Foreseeably, Richard Long has gone on since then to become a world-famous artist while I am no less content to have estab- lished some minor rapport with the intelli- gent readership of this paper. The signifi- cance of the Turner Prize is as a prime example of art-world realpolitik, whereby the general public is not merely asked but bludgeoned into accepting the unbeliev- able. While power, money and influence favour Long's view of his own art, I summon no other allies than time and reason.

Previous page

Previous page