Crafts

Five by Twelve: Studio Ceramics (Gallery North, till 23 December) Geoffrey Whiting, Potter (Aberystwyth Arts Centre, till 3 February and touring to Bath, London and Paisley) Claudi Casanovas (Galerie Besson, till 21 December)

Saying more with less

Tanya Harrod

What do we expect to see in an art gallery? Any old detritus can be magicked into art but on the whole the cultural guardians of these places are careful to exclude the applied arts. I must record for posterity the words of Joanna Drew, CBE, the director of the Hayward Gallery. At a recent conference she was asked why the Hayward did not show anything of the rich diversity of 20th-century crafts. 'The crafts, , : mused the distinguished bureau- crat with mild distaste, 'design, yes, but the crafts... I don't really know what they are.' This is the kind of 'arts administrator' to whom makers will have to turn if, on the recommendations of the Wilding Report, the Crafts Council loses its own gallery.

Yet before the war there were groups and galleries where avant-garde artists and potters exhibited together — the National Society, the Seven and Five Society, Pater- sons and Colnaghi, all showed other art forms with painting and sculpture. Happily the tradition is not quite dead. Last week I went up to Kirby Lonsdale to visit Gallery North, an altogether remarkable venture to find in a small town in Cumbria. Its director Ian Higginbotham mounts consis- tently ambitious exhibitions; his current show, The Advent Calendar: A Contem- porary View, includes work by 24 re- spected painters including Graham Crow- ley, Albert Irwin, Anthony Whishaw, De- rek Hyatt and Eileen Cooper. He has boldly combined this with work by 12 studio potters, and the strongest, simplest pieces, by Colin Pearson and Joanna Con- stantinidis, look very splendid alongside the paintings, commanding the floor space with all the élan of sculpture.

Of course there has always been a strong puritan strain in the studio ceramics move- ment that despised the very idea of exhibi- tions, galleries and indeed any contact with the fine art world. In his writings Bernard Leach passed on the gospel according to Dr Yanagi, the great spokesman for the Japanese arts and crafts revival. Yanagi reserved greatest praise for what he termed the unknown craftsman, working anony- mously within a strong tradition. Geoffrey Whiting, the subject of a posthumous retrospective at Aberystwyth, was touchingly true to this ideal — unlike Leach himself who was a consummate self-publicist.

Whiting gave up the life of a professional soldier to become a potter in 1949, inspired by Leach's A Potter's Book. He was one of many — the book's mixture of practical advice and a promise of spiritual fulfilment appealed to a whole generation of bruised and battered psyches that had survived the _war. As a potter in the West, but looking East for inspiration, Whiting worked hard to subsume his originality. Through repeti- tive work — throwing the same shape over and over again — he hoped to achieve the Sung standard, the ideal simplicity of form which Leach held dear. At their best Whiting's pots are harmonous and serene in the spirit of classical Chinese and Ko- rean pots; at their worst they are quiet to the point of dulness.

Seeing the whole range of Whiting's life's work — from bucolic mead sets to teapots to stately tall bottles — lends one to reflect on the isolation of the studio potter in Britain. What a contrast with the situation in Scandinavia where studio pot- ters and other artists are invited to work in studio by the ceramics industry. Such collaborations, as the V & A's current ex- hibition, Scandinavia: Ceramics and Glass in the Twentieth Century, makes clear, result in mass-produced wares of great beauty and freshness. Whiting had to battle on alone, suffering deep depressions that led to bouts of heavy drinking as he saw the ceramics scene changing, the Sung standard being thrown overboard and all his values undermined. He clung to notions of service, but the loveliest pieces in the exhibition at Aberystwyth reveal Whiting in a quiet way letting himself go. He wrote of his desire to say 'more and more with less and less' and perhaps he had in mind a little group of teabowls made in the mid- 1960s. Simply shaped by hand from a ball of clay, they are more direct and com- municative than all his thrown work; char- acteristically they were made for private study and never shown to the public.

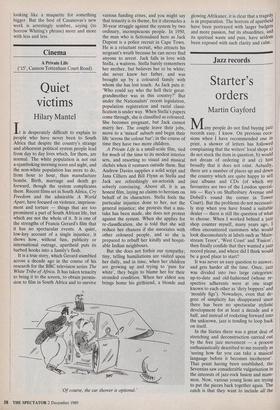

Finally, two exhibitions in London. You will have just missed a fine exhibition by Bernard Leach's widow Janet Leach at the Craftsmen Potters Shop. This Texan pot- ter, now in her seventies, showed majestic woodfired pots with all the massive effect of the mediaeval Bizen wares admired by the Japanese tea masters. Some of the finest large pieces were unsold and could be tracked down to her studio at St Ives. And at the Galerie Besson (15 Royal Arcade, 28 Old Bond Street, W1) the work of the Spanish potter Claudi Casanovas is worth seeing, if only to ruminate on the difference between craft and high art. He is like a pastoral member of the Boyle family, seemingly recreating random bits of the earth's surface. These used to be prettified into decoration but Casanovas is getting tougher. 'My method is to work badly', he writes. Ceramic sculpture can so easily hover on the edge of vulgarity or end up Wall plate, 1989, in stoneware and porcelain, by Claudi Casanovas looking like a maquette for something bigger. But the best of Casanovas's new work is arrestingly sombre, saying (to borrow Whiting's phrase) more and more with less and less.

Previous page

Previous page