DEMOS AGAINST DAYTON

Patrick Bishop drops in at a Serb bar, and

finds the regulars somehow untouched by the spirit of reconciliation

Sarajevo

IN MARCH 1941 crowds of Serbs took to the streets of Belgrade chanting their opposition to the deal that the outgoing government had struck with the Nazis. `Bolje Rat Nego Pakt!' (Better War than the Pact) they shouted, ringing the changes with `Bolje Grob Nego Rob!' (Better the Grave than a Slave). In cold print these may not seem the catchiest of slogans but in Serbo-Croat they have a neat rhyme and rhythm and one way or another the demonstrators' wishes were answered. The pact fell apart and the Serbs got their war.

Today the Serbs of Sarajevo had another pact to rail against. Under the terms of the peace agreement struck in Dayton, Ohio, the Bosnian capital will be reunited. The Serb suburbs, from where they have exer- cised their stranglehold on the city, will be reintegrated under the control of the Mus- lim-led Bosnian government. The besiegers will be forced to live with those they have been starving and shelling for most of the last three and a half years. In theory, shortly after the ceremonial signing of the agreement in Paris around 10 December, Muslim refugees driven out at the start of the war will be able to come back and reclaim their homes, many of which have been taken over by Serb squat- ters. The Nato troops of the Implementa- tion Force (IFOR) will be standing by to make sure they do so.

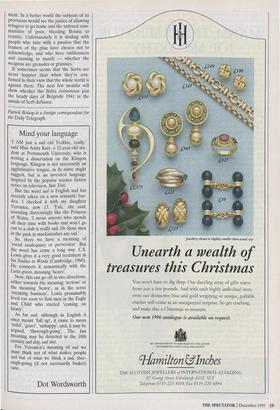

Unsurprisingly, the 40-60,000 Serbs affected by the plan are uneasy at the prospect. In smoky cafés and chilly bars they are planning a campaign of resistance that promises to deliver high drama in the weeks ahead. Defiance was running high in Ilidza's Beograd Bar when I dropped in a few days ago. Ilidza is a south-western suburb of Sarajevo. It once had a classy spa hotel — the Archduke Franz Ferdi- nand ate the last dinner of his life there before his rendezvous with Gavril Princip in June 1914 — but is now a dreary exam- ple of Titoist town planning; all commie concrete. It none the less inspires a touch- ing local patriotism. 'I would not exchange a stone of Ilidza for the whole of Saraje- vo,' said Gaja, a 45-year-old factory work- er as she sat with her pals drinking coffee and brandy. Talk of reconciliation with the Muslims they once lived alongside cuts little ice with the Beograd's regulars, well steeped in the propaganda pumped out by the local media during the years of war. 'They force their women to wear head scarves and they are dirty. They put their stables next to their houses,' said sullen-looking Zoran. Jovan, a fiercely-mustachioed 45-year-old, summed up the mood of the meeting. 'If they dare to come here we won't spare anyone,' he barked. 'Everyone has a hand grenade in his pocket here. Nato or the Muslims they're not welcome.'

The demos have begun already with war veterans and youths parading around town while their younger brothers throw rocks at passing vehicles. The local authorities, who are out of step with the mood on the streets, have tried to stop the marches and blame trouble-makers from the ultra- nationalist Radical Party in Serbia proper for stirring things up. Police have orders to stop the stone-throwing. The local Serbs, many of whom are contemptuous of their leaders after what they see as the sell-out in Dayton, have more potent stratagems up their sleeves, however.

Despite his talk of grenades Jovan puts more faith in other traditional weapons of the Bosnian war — children and grannies. These may seem trifling assets faced with the might of the IFOR and the determination of the international community to get the whole ghastly business settled, but the deployment of innocents and black-clad wid- ows to block troop movements and stymie convoys has proved a highly effective Serb tactic in the history of this conflict.

The Mark 1 surface-to-surface hate-guid- ed Crone missile is one of the most fear- some weapons in the Balkan armoury. Battling grannies played havoc with UN efforts to get aid to the starving Muslim enclaves of eastern Bosnia in the winter of 1992. On the Croat side, in the summer of 1993 they led the assault on the 'Convoy of Joy' bringing food to the Muslims of cen- tral Bosnia.

The prospect of civilians lying down in the path of departing UN vehicles was one of the nightmares that haunted Nato com- manders as they drew up their plans to extract the UN Protection Force from Bosnia this year.

Faced with a sea of children and ancients and the attendant media hordes, it would be a brave commander who chose a robust interpretation of the orders stemming from the Dayton agreement.

Jovan and his mates are only too aware of this. 'Nato is not going to kill our chil- dren,' he said reasonably. 'So we will use them as shields.'

Already the grannies are limbering up. On Sunday they mounted an inaugural demo, gathering in an Ilidza graveyard to shout an invitation to the 'traitor' Serb President Slobodan Milosevic to 'come here and count our dead'.

The Dayton agreement is a fine docu- merit. In a better world the subjects of its provisions would see the justice of allowing refugees to go home and the tattered com- munities of poor, bleeding Bosnia to reunite. Unfortunately it is dealing with people who hate with a passion that the framers of the plan have chosen not to acknowledge, and who have ruthlessness and cunning to match — whether the weapons are grenades or grannies. It sometimes seems that the Serbs are never happier than when they're con- firmed in their view that the whole world is against them. The next few months will show whether the Ilidza evenements join the heady days of Belgrade 1941 in the annals of Serb defiance.

Patrick Bishop is a foreign correspondent for the Daily Telegraph.

Previous page

Previous page