Keeping up appearances

Jane Gardam

THE ART OF DRESS: FASHION IN ENGLAND AND FRANCE, 1750-1820 by Aileen Rubeiro Yale, £40, pp. 264 'leen Rubeiro is head of the History of Dress department at the Courtauld Institute and Reader in History of Art at London University, and this book is about fashion seen through the eyes of the superb portrait painters of 18th-century England and France.

1750-1820 include terrifying, dramatic years. Even clothes could be affected, sometimes dictated, by politics. Fashion could swing sentimentally back to a more romantic past and further back still to a classical past in times of celebration, like the coronation of Napoleon. Not that there has ever been anything like the coronation of Napoleon. Rubeiro examines dressing up and 'fancied dress' and clothes 'in rela- tion to the fabric of society'. 'Truth and History' is the subtitle to the Introduction. The whole thing is so massively informed that it's a pity it's so difficult to read, but it is and I defy anybody to sit down and read it through unless it's a student with a note- book and imminent exam.

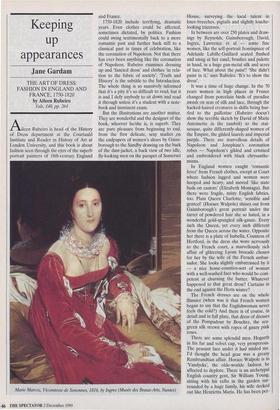

But the illustrations are another matter. They are wonderful and the designer of the book, whoever he/she is, is superb. They are pure pleasure from beginning to end, from the first delicate, sexy studies ,on the endpapers of women's shoes by Gains- borough to the Sandby drawing on the back of the dust-jacket, a back view of two idle, fly-looking men on the parapet of Somerset Marie Marcoz Vicomtesse de Senonnes, 1816, by Ingres (Musee des Beaux-Arts, Nantes) House, surveying the local talent in knee-breeches, pigtails and slightly louche- looking tricornes.

In between are over 250 plates and draw- ings by Reynolds, Gainsborough, David, Ingres, Lawrence et al — some fine women, like the self-portrait frontispiece of Adelaide Labille-Guillard seated flushed and smug at her easel, brushes and palette in hand, in a huge gun-metal silk and acres of lace. What about the paint? 'She didn't paint in it,' says Rubeiro. 'It's to show the dress'.

It was a time of huge change. In the 70 years women in high places in France changed from porcelain birds of paradise awash on seas of silk and lace, through the hacked-haired creatures in shifts being hus- tled to the guillotine (Rubeiro doesn't show the terrible sketch by David of Marie Antoinette in the tumbril) to the stat- uesque, quite differently-shaped women of the Empire, the gilded laurels and imperial purple. There are marvellous details of Napoleon and Josephine's coronation robes — Napoleon's gilded and ermined and embroidered with black chrysanthe- mums.

In England women caught 'romantic fever' from French clothes, except at Court where fashion lagged and women were hooped and heavy, and moved 'like state beds on castors' (Elizabeth Montagu). But there were fragile, misty English fabrics, too. Plain Queen Charlotte, 'sensible and genteel' (Horace Walpole) shines out from Gainsborough's great portrait under the turret of powdered hair she so hated, in a wonderful gold-spangled silk-gauze. Every inch the Queen, yet every inch different from the Queen across the water. Opposite her there is a plate of Isabella, Countess of Hertford, in the dress she wore nervously to the French court, a marvellously rich affair of glittering Lyons brocade chosen for her by the wife of the French ambas- sador. She looks slightly embarrassed by it — a nice home-counties-sort of woman with a well-washed face who would be com- petent at churning the butter. Whatever happened to that great dress? Curtains in the end against the Herts winter?

The French dresses are on the whole flimsier (when was it that French women began to say that the Englishwoman never feels the cold?) And there is of course, in detail and in full plate, that dress of dresses of the Pompadour by Boucher, the sea- green silk strewn with ropes of gauzy pink roses.

There are some splendid men. Hogarth in his fur and velvet cap, very prosperous. The peasant face under it had misled me. I'd thought the head gear was a greasy Rembrandtian affair. Horace Walpole is in Nandycks', the olde-worlde fashion he affected to deplore. There is an archetypal English country gent, Sir William Young, sitting with his cello in the garden sur- rounded by a huge family, his wife decked out like Henrietta Maria. He has been per- suaded into great patches of Restoration lace, 'like doilies', and a swatch of early-Stuart hair. And the parvenue, Sir Edward Turner, with his funny little woman's account-keeping face, is full length in a dreadful three-piece suit of black French silk with a wallpaper pattern of flowers trickling all over it. He looks uncertain.

The last plates are George IV, 'the image of elephantine splendour', painted by Lawrence for his coronation. He is painted 20 years too young and wears a windswept peruke. 'Some gorgeous bird of the east'. A sheet of ermine lines a ruby-red velvet cloak like a sultan's tent. Across the page is a last little bizarre engraving of him en route to his crowning in silver tissue over corsets, the train of the same cloak being heaved along at waist level by 'eight sons of peers' (though there are nine) dishy young clones in striped, melon-like knicker-bockers, short, egg-shaped cloaks and hats invisible under meringues of curly Turkish feathers. The ceremony took nine hours, the king fainted from the heat and the corsets, and everybody said it was just like The Faery Queen.

Well, maybe the text is more fun than I thought. The book would certainly make a wonderful present. Look at it through the long winter evenings and mourn all the colour and nonsense — and art — that has drained away.

Previous page

Previous page