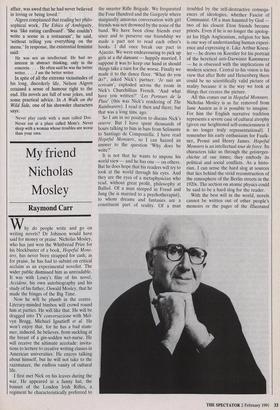

My friend Nicholas Mosley

Raymond Carr

Why do people write and go on writing novels? Dr Johnson would have said for money or praise. Nicholas Mosley, who has just won the Whitbread Prize for his blockbuster of a book, Hopeful Mons- ters, has never been strapped for cash; as for praise, he has had to subsist on critical acclaim as an experimental novelist. The wider public dismissed him as unreadable. It was with Losey's film of his novel, Accident, his own autobiography and his study of his father, Oswald Mosley, that he made the fringes of the Big Time.

Now he will be plumb in the centre. Literary-minded bimbos will crowd round him at parties. He will like that. He will be dragged into TV conversazione with Mel- vyn Bragg, Michael Ignatieff et al. He won't enjoy that, for he has a bad stam- mer, induced, he believes, from suckling at the breast of a gin-sodden wet-nurse. He will receive the ultimate accolade: invita- tions to lecture to creative writing classes in American universities. He enjoys talking about himself, but he will not take to the razzmatazz, the endless vanity of cultural life.

I first met Nick on his leaves during the war. He appeared in a funny hat, the bonnet of the London Irish Rifles, a regiment he characteristically preferred to

the smarter Rifle Brigade. We frequented the Four Hundred and the Gargoyle where marginally amorous conversation with girl friends was not drowned by the noise of the band. We have been close friends ever since and to preserve our friendship we made a pact not to read each other's books. I did once break our pact in Ajaccio. We were endeavouring to pick up girls at a the dansant — happily married, I suppose it was to keep our hand in should things take a turn for the worse. Finally we made it to the dance floor. 'What do you do?', asked Nick's partner. `.1e suis un ecrivain', exploded across the room in Nick's Churchillian French. 'And what have you written?' Les Porteurs de la Pluie' (this was Nick's rendering of The Rainbearers). I read it then and there; but that was a long time ago.

So I am in no position to discuss Nick's oeuvre. But I have spent thousands of hours talking to him in bars from Selinunte to Santiago de Compostella. I have read Hopeful Monsters, so I can hazard an answer to the question 'Why does he write?'

It is not that he wants to impose his world view — and he has one — on others. But he does hope that his readers will try to look at the world through his eyes. And they are the eyes of a metaphysician who read, without great profit, philosophy at Balliol. Of a man steeped in Freud and Jung (he is married to a psychotherapist), to whom dreams and fantasies are a constituent part of reality. Of a man

troubled by the self-destructive consequ- ences of ideologies, whether Fascist of Communist. Of a man haunted by God two of his closest Eton friends became priests. Even if he is no longer the apolog- ist for High Anglicanism, religion for him is one way of understanding human experi- ence and expressing it. Like Arthur Koest- ler — he draws on Koestler for his portrait of the heretical anti-Darwinist Kammerer — he is obsessed with the implications of modern science. Central to his vision is his view that after Bohr and Heisenberg there could be no scientifically valid picture of reality because it is the way we look at things that creates the picture.

All this comes out in Hopeful Monsters. Nicholas Mosley is as far removed from Jane Austen as it is possible to imagine. For him the English narrative tradition represents a severe case of cultural atrophy (given our heightened self-consciousness it is no longer truly representational). I remember his early enthusiasm for Faulk- ner, Proust and Henry James. Hopeful Monsters is an intellectual tour de force. Its characters take us through the geisterges- chichte of our times; they embody its political and social conflicts. As a histo- rian, I can sense the hard slog at sources that lies behind the vivid reconstruction of the atmosphere of the Berlin streets in the 1920s. The section on atomic physics could be said to be a hard slog for the reader.

With the best will in the world, novels cannot be written out of other people's memoirs or the pages of the Illustrated London News — one of Mosley's sources. There is direct observation. Of women, for example. Falling in love may be the open- ing round in a battle that will expose the depths of the human psyche. But living one's life as a search for copy has its limitations. The 'free association of men and women', Eleanor observes in Hopeful Monsters, distracts one from 'the need to make sense of things'. To make sense of things, Nick has imposed a cell-bound asceticism on himself. A steady daily eight- hour stint.

All this may make Nick sound an in- human bore, a pretentious if kindly guru. That is the last thing he is. He is a wonderful companion and a very funny man — funny, not witty. The smart one- liner is not his style. He revels in old jokes; the chaplain of his regiment greeting an inedible dish as 1 he piece of cod that passeth all understanding'.

For Nick it is in extreme situations that people and ideologies reveal and test them- selves. 'Sticking it out' is a phrase I've often heard him use — it crops up in Hopeful Monsters. He could have opted out of the war. Taken prisoner on his first day in action he ran off and was saved from being shot by a fluke; his company com- mander picked off his pursuer at 200 yards. Scarcely surprisingly, he believes in what Kundera calls 'the birds of fortuity' that alight on our shoulders. Or is there a pattern? How, one of his characters won- ders, can accidental mutations in the gene pool explain the evolution of complex organs like the human eye. Another des- cent of the bird of fortuity. For his chapter on the Spanish Civil War Nick read the extraordinary unpublished memoirs of the aunt of the literary editor of The Spectator, who asked me to write this profile.

I end that profile on a note of despera- tion. Do I really know the man who wrote Hopeful Monsters, even after half a cen- tury's friendship? We worry about differ- ent things. He about man's self- destructiveness and the possibilities of redemption. Myself whether the National Trust will stymie stag-hunting on Exmoor. We came from different gene pools and have lived in different environments. While he was winning an MC in Italy, I was a dominie in a minor public school in Berkshire. The political and private lives of his parents were public property. His father, Oswald Mosley, was for many of his class an untouchable; my mother-in-law found his manners 'flashy' and would not have him in the house. My father was a much-loved country schoolmaster. His re- lations talked about relations, mine about things. He has the novelist's well furnished mind. I've nothing to write about. Still, I must cheer up. Nick is about to take me and his family to a celebratory beano at the Savoy Grill.

Hopeful Monsters is published by Secker & Warburg at £14.95.

Previous page

Previous page