Exhibitions

Gus Cummins (Gardner Centre, University of Sussex, till 9 February)

Unknown forces

Giles Auty

Anumber of artists I respect, John Bellany and Mick Rooney among them, urged me to drive to Brighton last weekend to see the current exhibition of paintings by Gus Cummins. Clearly Cummins is that often overlooked animal, a painters' pain- ter. Unlike many who work in our modern museum service, artists recognise that art is a business which involves execution as well as ideas. To its credit, the general public is also aware of this elementary fact, which is why exhibitions by artists of obvious accomplishment are so popular. Some years ago, those who run New York's most important museums turned down the chance to house an exhibition of work by Lucian Freud, Britain's most accomplished living artist. His exhibition opened in Washington instead to extraordinary pub- lic and critical acclaim.

Most of us enjoy the thought that a major talent may be living unrecognised in our midst. Yet since I began writing for this weekly nearly seven years ago, I have come across but four living artists of stature whose work was previously un- known to me. None of them came from this country. The first was Marie-Louise von Motesiczky who showed at the Goethe Institute at the end of 1985. The second was Lotte Laserstein, subject of exhibi- tions at Agnew's and the Belgrave Gallery two years later. The other two were the Spanish realists Antonio Lopez Garcia and Manuel Lopez Villasefior, who exhibited at Marlborough Fine Art and at Agnew's in 1986 and 1988 respectively.

Good art does not happen by accident and thus will always be a commodity in short supply. By contrast, over-praised art is commonplace today, in Britain as else- where. My views on a number of over- exalted British artists may be known to you already. Unfortunately, once enough money and promotional power have been put behind the creation of a reputation which is unjustified by talent, the resulting myth becomes hard to stop — within the short term, at least. What, then, of Gus Cummins, our largely unsung hero?

Cummins won a prize at the Royal Academy Summer Show in 1987 and car- ried off the valuable Hunting Group Prize last year at the Mall Galleries. Yet his work is held by many to be excessively sombre and thus difficult to sell. It would seem odd, otherwise, that Cummins has not attracted the attentions of a major dealer.

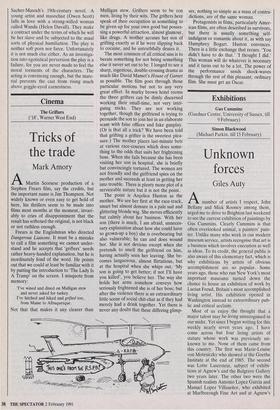

The current exhibition at the Gardner Centre, University of Sussex (Falmer, near Brighton), comprises 23 works completed over the past five years or so. The artist's working method and subject matter mean that each painting needs a good deal of time and effort to produce. Most are large and highly complex compositions featuring a clutter of objects found in what looks like a garden shed. Blow-torches, saws, lad- ders, frames, grilles, a shoe-last or two, a hoop, pieces of trellis, specimen cases and the like are woven into complex patterns of light and shadow. Drawing curves and the remains of an up-ended piano and typewri- ter join occasionally in this dusty detritus. Wooden racks, plumb-lines and cog- wheels add further visual frameworks to old cages and stuffed birds. Sepias and blacks intermingle, such little bright colour as there is coming from a polished sphere

or set of mannikins. Outside such typical works there are two finely made paintings of the skeleton of a chicken and two interiors of a church with builders' scaf- folding.

What, if anything, does this all mean? Are we dealing with a twilit world of dream, memory and nostalgia or with some tortuous form of allegory? Names such as Ensor, de Chirico and Tunnard passed through my mind but soon sped out again. The artist's titles flirt with the portentous — 'Stored Alchemy', 'Sombre Ordinance', 'Before the Event' — yet these strike me as a smokescreen. Are we dealing here with a subject worthy of Tallulah Bankhead's 'There's less in this than meets the eye'? Cummins's paintings are highly competent yet strangely unsatisfying withal. They are full of structure and complexity yet seem low on intended meaning. Their form is poetic but the result is not poetry. I enjoyed the exhibition thoroughly nonetheless, not least for the artist's dedi- cation to drawing and structure.

Structure is unfortunately in short supply in the art of Simon Blackwood, subject of a large-scale exhibition at Michael Parkin (11 Motcomb Street, SW1), though bright and cheerful colour certainly is not. Black- wood is described as a new romantic luminist and has been acclaimed as such in USA and Japan where they know what such descriptions mean. He has studios at Hawick and the Bosphorus and will be using the former at present, one presumes. If the sober hues of the Scottish Borders could persuade Mr Blackwood to tone down his chromatic exuberance and look harder at his drawing, this enforced winter- ing would have been spent well. A small work such as 'River, Trees and Buildings' shows what the artist is capable of when persuaded away from unbridled euphoria.

'Diptych', 1985, by Gus Cummins

Previous page

Previous page