THE LONDON LITTER BUGS

The public are lectured about dropping rubbish. But it is councils who are responsible for the capital's

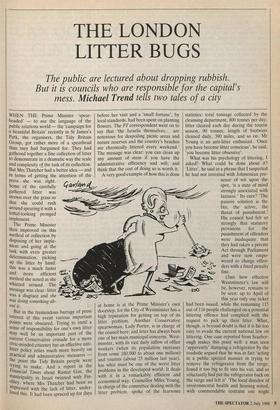

WHEN THE Prime Minister 'spear- headed' — to use the language of the public relations world — the 'campaign for a beautiful Britain' recently in St James's Park, the organisers, the Tidy Britain Group, got rather more of a spearhead than tney had bargained for. They had gathered together a fine collection of litter to demonstrate in a dramatic way the scale and complexity of the task of its collection. But Mrs Thatcher had a better idea — and in terms of getting the press she was right. Some of the carefully gathered litter was strewn over the grass so that she could rush around spearing it with a lethal-looking pronged implement. attention of the The Prime Minister then improved on this method of collection by disposing of her imple- ment and going at the task with even greater determination, picking Up the litter by hand: this was a much faster and more efficient method she noted as she Whizzed around. The message was clear: litter /3 was a disgrace and she was doing something ab- out it.

But in the tremendous barrage of press interest at this event various important Points were obscured. Trying to instil a sense of responsibility for one's own litter 'hay well be an important part of the current Conservative crusade for a more civic-minded citizenry but an effective anti- litter policy relies much more heavily on practical and administrative measures — the point the Tidy Britain people were trying to make. And a report in the Financial Times about Ramat Gan, the municipality in Israel twinned with Fin- Ch ley, where Mrs Thatcher had been so impressed with the lack of litter, under- lined this. It had been spruced up for days before her visit and a `small fortune', by local standards, had been spent on planting flowers. The FT correspondent went on to say that 'the Israelis themselves.., are notorious for despoiling picnic areas and nature reserves and the country's beaches are chronically littered every weekend.' The message was clear: you can clean up any amount of mess if you have the administrative efficiency and will; and think that the cost of doing so is worth it.

A very good example of how this is done at home is at the Prime Minister's own doorstep, for the City of Westminster has a high reputation for getting on top of its litter problem. Another Conservative spearwoman, Lady Porter, is in charge of the council here; and litter has always been one of her main municipal concerns. West- minster, with its vast daily inflow of office workers (when its population increases from some 180,000 to about one million) and tourists (about 23 million last year), has what must be one of the worst litter problems in the developed world. It deals with it in a remarkably efficient and economical way. Councillor Miles Young, in charge of the committee dealing with the litter problem, spoke of the fearsome statistics: total tonnage collected by the cleansing department, 800 tonnes per day; litter cleared each day during the tourist season, 90 tonnes; length of footways cleaned daily, 390 miles, and so on. Mr Young is an anti-litter enthusiast. `Once you have become litter conscious', he said, 'you become litter obsessive'.

What was his psychology of littering, I asked? What could be done about it?

litter', he said in a phrase that I suspected he had not invented with Johnsonian pre- sence of wit upon the spot, 'is a state of mind strongly associated with laziness.' Its cure? 'The passive solution is the bin; the active, the threat of punishment.' His council had felt so strongly that statutory provisions for the punishment of offenders were inadequate that they had taken a private Act through Parliament and were now empo- wered to charge offen- ders with a fixed penalty fine.

(Just how effective - Westminster's law will be, however, remains to be seen: up to April of this year only one ticket had been issued, while the remaining 115 out of 116 people challenged on a potential littering offence had complied with the request to pick up their litter. What, though, is beyond doubt is that it is far too easy to evade the current national law on littering. One case reported from Scarbor- ough makes this point well: a man seen 'apparently' dumping a refrigerator by the roadside argued that he was in fact 'acting in a public spirited manner in trying to remove the refrigerator from the verge, found it too big to fit into his van, and so reluctantly had put the refrigerator back on the verge and left it'. The local director of environmental health and housing noted, with commendable restraint one might think: 'This was an interesting, if unlikely, explanation and one which proved impossi- ble to refute.') 'Now, as to bins.. % Councillor Young went on. There are some 6,000 of these, many of them sponsored, which make a marginal profit. Much modern fast-food packaging — a huge and growing litter problem — is far too rigid for the bins. 'It only takes a few pizza boxes to prevent a bin being used any further before it is emptied. I am organising a seminar on this aspect of the matter with the fast-food shops later in the year.' 'And then there is the black-bag problem...' I needed no further persuading that Mr Young was well matched for his task.

What had been most revealing, howev- er, and it was the sane feeling that I got from talking to Mr Robert Seear, the council officer in charge of Westminster's street cleaning, was the way in which the two men spoke of their work in a business- like way. One heard of 'cost centres' and 'corporate image' — Westminster's street cleaners wear uniforms and have just been given newly-designed summer sweat-shirts. And the city council monitors the results of its labour force — 'we pioneered the photometric approach in this country', Mr Young told me proudly. So he explained in some detail a devilishly complex system of 'grid-building' from photographs taken at fixed points on a random basis and then examined for 'litter evidence'.

For the most striking contrast, you need only cross into the next London borough to the north — Camden. Indeed, as you go over the boundary itself the change be- comes quite dramatic. For years the two councils had followed a commonly- adopted procedure of one council looking after about a half of the streets where the boroughs meet and the other the others. Westminster have recently stopped this with Camden because they did not feel that their ratepayers were getting anything like a proper service from their sister borough: there had been many complaints from Westminster ratepayers being swept (or, more to the point, not being swept) by Camden's workforce. Now the streets of the boundary are, ludicrously, half-swept by Westntinster, half-swept by Camden. One can see this for oneself on the Charing Cross Road between Centre Point and Cambridge Circus. I conducted an 'on-the- spot investigation' with a complicated measuring system entirely of my own devising — so many points deducted for bottles, cans, sweet-wrappings, cigarette ends, etc: on the Soho side Westminster achieved a score of some 85 per cent, while Camden — for which I had to set up two new categories for parts of a broken lamp-post and large cardboard boxes — was in the 40s.

Things get worse the deeper into Cam- den you venture. Bloomsbury Square was appallingly messy; my measuring scale broke down here — registering a minus score before I had gone even ten yards. And the prospect that meets you around Argyle Square and the King's Cross district would be enough surely to blunt even the Prime Minister's sharpest pronging device. Moreover, there is worse to come for Camden: at a meeting of its building works and services committee in February the acting director of finance said that in order to achieve a 'lower budget level' (or as Camden's critics would say, 'in order to cut former profligate waste of taxpayers' money'), 'changes in the level of service' would be required. What were these 'changes'? A separate report from the director of works spelt them out: 'the probability that many [refuse] collections will be missed' and 'a reduced street cleaning service, with residential streets swept every four weeks'. Things may not be quite this bad yet the council says; but this is clearly the direction they are head- ing. Westminster, however, sweeps every street twice a week, many of them every day, some of them many times a day.

How does Camden compare to West- minster in financial terms in rubbish collec- tion and street litter services? It is impossi- ble to answer this question with proper 'I think you may find that this m. akes you amusingly mindless.' precision because, in common with other left-wing councils, it does not submit fi- gures to the Chartered Institute of Public Finance and Accountancy. But it is possi- ble to work out a fair comparison between the two from their budget figures. West- minster spends some £12.3 million; Cam- den some £6 million. Westminster deals with just under 300,000 tonnes of rubbish a year to Camden's just under 100,000. (This figure includes the tonnage from their elaborate recycling programme, of which they are particularly proud.) So, taking into account the saving in labour costs that the recycling programme should bring to Camden, Westminster collects and dis- poses of more than three times Camden's rubbish at about only two times the cost to its ratepayers. And Westminster has achieved this while steadily reducing its overall costs in recent years while Cam- den's have, until now, headed ever up- wards. Put another way, one could say that on a cost-per-tonne basis Westminster's services, on top of being almost incompa- rably better, cost something less than two-thirds of Camden's, where the services are already very poor and seem set to deteriorate further.

Why is this? The simple answer is that in Camden the managers don't manage and the business of providing local services is not pursued in a business-like way as it is in Westminster. I saw for myself street clean- ers in Camden going at their work with less than enthusiasm; I noticed in particular that they were of a gregarious nature often stopping to chat with each other and catching up on the news. 'After all', their argument seems to go, 'at the town hall the office workers do this all day.' When the number of staff of the Camden and West- minster cleaning workforce are taken into consideration (some 443 for Camden and 803 for Westminster) the ratio of 3:2 in Westminster's favour in terms of costs swings still further in its favour in terms of the effectiveness of its labour and — probably much more important — of its management.

The government response to this sort of situation has been the Local Government Act which received the royal assent earlier this year. However, it probably goes no- where near far enough to ensure a real change. For although the new Act will ensure that the provision of many services, including rubbish and litter collection, goes out to tender, there is no statutory require- ment for a local authority to achieve any particular level of service.

Moreover, as one senior local govern- ment official put it to me, it's more than likely that in most cases — probably all cases in Labour-controlled areas — the local authorities will award the contracts to their own former direct labour organisa- tions — 'thereby fulfilling the prophecy that they have stuck to all along, that "their people" do it best'. This is a joke; a bad and expensive joke.

Previous page

Previous page