REVIEW OF THE AR'TS

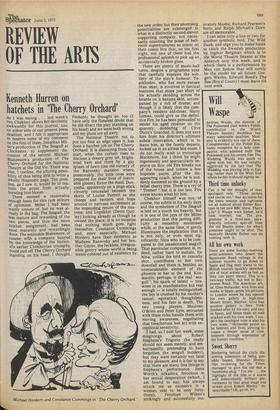

Kenneth Hurren on hatchets in "Me Cherry Orchard'

As I was saying . . . last week's two Chekhov shows fell devilishly awkwardly for this journal, one en either side of our present press deadline, and I felt it appropriate to reserve some of my comment on the first of them, Jonathan Miller's production of The Seagull at Chichester, to supplement dis cussion of the second, Michael Blakemore's production of The Cherry Orchard for the National Theatre at the Old Vic. There was also, I confess, the alluring possi

bility of thus being able to write a Wholly rhapsodic page. The problem. as I saw it, would be to restrain the prose from actually1 bursting into bloom.

There seemed a reasonable enough basis for this rare seizure of optimism. Miller I had been Warily unsure of, but he was already in the bag: The Seagull, the less mature and rewarding of the two pieces, and thus the more ticklish assignment, had been ; most maturely and rewardingly , done. The estimable Blakemore, of course, with a company buoyed ; by the knowledge of the Nation' al's earlier Chekhovian triumphs, could pull off The Cherry Orchard standing on his head; I thought.

Probably he thought so, too (I have only the flimsiest doubt that he did direct the play standing on his head) and we were both wrong and my plans are all awry.

The National Theatre, not to put too fine an edge upon it, has done a hatchet job on The Cherry Orchard. It is dismaying from the start, when the curtain rises to disclose a dreary grey set, brightened here and there by a gay splash of fawn (the old nursery of the Ranevsky mansion where, presumably, the little ones were prepared for their lives of inevitable gloom). Enter the maid, Dunyasha, apparently on a pogo-stick cleverly concealed beneath the skirts of Louise Purnell as she cheeps and twitters and hops around in nervous excitement at the impending return of the mistress; and Lopakhin (Denis Quitley) looking already as though he owned the place. It is no surprise that nothing much goes right thereafter. Constance Cummings and, more especially, Michael Hordern have their moments as Madame Ranevsky and her brother Gayev, the feckless, irresponsible gentry whose world is being steam-rollered out of existence by ,

the new order; but their promising potentialities are submerged in what is a distinctly second-eleven supporting company, not necessarily counting the posse of ballroom supernumaries so intent on their comic bits that, on the first night, not one of them had the professional aplomb to pick up an i accidentally broken glass.

There are plenty of music-hall turns, despite a programme note that carefully explains the subtlety of the play's humour. Yepikhodov, who has more excuse than most, is involved in farcical business that stops just short of I his actually skidding across the boards on a banana-skin, accompanied by a roll of drums; and though it is likely that the company's resident old-timer, Harry Lomax, could give us the definitive Firs, he has been persuaded to model his aged retainer on the quavery, doddering of Clive Dunn's Grandad. It does not save him from his director's ultimate subtle innovation, which is to leave him, as the family departs, locked up in an airless box-room. I do not really wish to encourage Blackmore, but I think he might ingeniously and spectacularly improve on this: old Firs breaks out of the house and totters a few hopeless paces after the disappearing coach, when he is suddenly slammed to the ground by a felled cherry tree. There is a cry of " Timber! " but it is too late. Firs never knows what hit him.

Chekhov himself was not, of course, too subtle in his early days and the symbolism of The Seagull is laid on a touch too heavily, but it is one of the joys of the Miller production that this jarring difficulty is smoothly minimised while, at the same time, it gently illuminates the implication that it is not only, or even most significantly, Nina who is to be compared to the assassinated seagull. That particular comparison is, indeed, rather hard to sustain, for Nina, unlike the bird so casually shot, contributes to her own downfall and there is, besides, an unmistakeable element of the phoenix in her at the end. Konstantin, perhaps, is the real 'seagull I: his spark of talent — tiresome in its manifestation but real enough — is totally extinguished; the boy is crushed by his mother's casual, egotistical thoughtlessness, and his fate is death. The two young players, Maureen O'Brien and Peter Eyre, entrusted with these roles handle them with moving awareness, negotiating that treacherous last act with exceptional sensitivity.

I had, as I said last week, some misgivings about Robert Stephens's Trigorin (he really should not seem merely, and embarrassedly, pretending to have forgotten the seagull incident), but they were certainly not fatal to my pleasure, and it is fair to say that there are many fine things in Stephens's performance. Irene Worth's Arkadina, ferocious in her sexual desperation (which, I am bound to say, has always struck me as excessive in a woman said to be only forty three); Penelope Wilton's strikingly and successfully inn ovatory Masha; Richard Pearson's Sorin and Ralph Michael's Dorn are all memorable.

I can seize only a line or two for another symbolic bird, The Wild Duch, and urge you to make haste to catch the Swedish production by Ingmar Bergman which is in the World Theatre Season at the Aldwych only this week, and in which there is a performance by Max von Sydow that will surely be the model for all future Gregers .Werles. Edward Bond's The Sea (Royal Court) 1 must leave till next week.

Previous page

Previous page