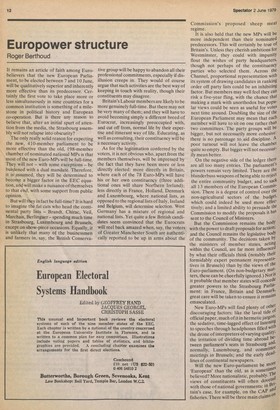

Europower structure

Roger Berthoud

It remains an article of faith among Eurobelievers that the new European Parliament, to be elected between 7 and 10 June, will be qualitatively superior and inherently more effective than its predecessor. Certainly the first vote to take place more or less simultaneously in nine countries for a common institution is something of a milestone in political history and European co-operation. But is there any reason to believe that, after an initial spurt of attention from the media, the Strasbourg assembly will not relapse into obscurity?

The only really solid reason for expecting the new, 410-member parliament to be more effective than the old, 198-member chamber of nominated national MPs is that most of the new Euro-MPs will be full-time. They will not — with some exceptions — be burdened with a dual mandate. Therefore, it is assumed, they will be determined to become a bigger factor in the EEC equation, and will make a nuisance of themselves to that end, with some support from public opinion.

But will they in fact be full-time? It is hard to imagine the fat cats who head the continental party lists — Brandt, Chirac, Veil, Marchais, Berlinguer — spending much time in Strasbourg, Luxembourg and Brussels, except on show-piece occasions. Equally, it is unlikely that many of the businessmen and farmers in, say, the British Conserva tive group will be happy to abandon all their professional commitments, especially if disillusion creeps in. They would of course argue that such activities are the best way of keeping in touch with reality, though their constituents may disagree.

Britain's Labour members are likely to be more genuinely full-time. But there may not be very many of them; and they will have to avoid becoming simply a different breed of Eurocrat, increasingly preoccupied with, and cut off from, normal life by their expertise and itinerant way of life. Educating, as well as consulting, their constituency will be a necessary activity.

As for the legitimation conferred by the voters, it is not obvious who, apart from the members themselves, will be impressed by the fact that they have been more or less directly elected: more directly in Britain, where each of the 78 Euro-MPs will have his or her own constituency (three additional ones will share Northern Ireland); less directly in France, Holland, Denmark and Luxembourg, where national lists, as opposed to the regional lists of Italy, Ireland and Belgium, will determine selection. West German); has a mixture of regional and national lists. Yet quite a few British candidates seem convinced that the Eurocrats will reel back amazed when, say, the voters of Greater Manchester South are authentically reported to be up in arms about the Commission's proposed sheep meat regime.

It is also held that the new MPs will be more independent than their nominated predecessors. This will certainly be true of Britain's. Unless they cherish ambitions for Westminster, they could with impunity flout the wishes of party headquarters, though not perhaps of the constituency parties who selected them. Across the Channel, proportional representation with its system of drawing candidates in ranking order off party lists could be an inhibiting factor. But members may well feel they call risk a five-year fling, with the chance that making a mark with unorthodox but pork' lar views could be seen as useful for votes next time around. Doubling the size of the European Parliament may mean that each member will have to sit on one rather than two committees. The party groups will he bigger, but not necessarily more cohesive: there is no patronage to aid discipline. A poor turnout will not leave the chamber quite so empty. But bigger will not necessarily mean better.

On the negative side of the ledger there are all too many entries. The parliament's powers remain very limited. There are the blunderbuss weapons of being able to reject the entire community budget, and to sack all 13 members of the European Commis' sion. There is a degree of control over the non-agricultural sectors of the budget, which could indeed be used more effectively; and a limited ability to persuade the Commission to modify the proposals it has sent to the Council of Ministers.

But the Commission remains the bodY with the power to draft proposals for action; and the Council remains the legislative bodY of the community. The decisions taken hY the ministers of member states, acting within the Council, are far more influenced by what their officials think (notably their formidably expert permanent representatives in Brussels) than by the views of the Euro-parliament. (On non-budgetary matters, these can be cheerfully ignored.) Nor is it probable that member states will concede greater powers to the Strasbourg Paha' ment: in France, Britain and Denmark, great care will be taken to ensure it remains emasculated.

New Euro-MPs will find plenty of other, discouraging factors: like the level tide OI official paper, much of it in hermetic jargon; the sedative, time-lagged effect of listening to speeches through headphones filled it the drone of interpreters of varying quality; the irritation of dividing time abroad he: tween parliament's seats in Strasbourg anu' normally, Luxembourg, and committee meetings in Brussels; and the early deadlines of continental newspapers. Will the new Euro-parliament be n1°1.! 'European' than the old, as is sometinte: believed? More nationalistic, probably. Th.', views of constituents will often doveta!' with those of national governments: in Orici tam's case, for example, on the CAP all fisheries. There will be three main claiMs °I' members' loyalties: national, local and Party, with plenty of conflicts between and even within each element. A UK constituency, or Italian region, could embrace deprived urban areas as well as many farmers, whose views on higher food prices Would be diametrically opposite. Some British candidates feel that the diverging interests of urban and rural populations will be one of the new parliament's main themes, With the Left broadly favouring the urban Poor and consumers, and the Right farmers and businessmen.

. Both the role of parliament and its working methods discourage ideological warfare. The main differences between the Parties are thrashed out in committee. Conclusions are embodied in a report, presented to the full assembly by a rapporteur, With the spokesmen of the political groups giving their views before a general debate. A narrow vote on a resolution means nil impact. Only by a measure of unanimity can Parliament's view be made clear. IdeologiFal differences there are. Broadly, the Left is against multinationals, co-operation on defence procurement, aspects of the CAP, and oppression in southern Africa and Latin America. The Right is against excessive interference either in business or the CAP, oppression in the Soviet bloc, and favours co-operation on defence procurement. But the pressure is towards consensus: no bad thing, some critics of Westminster may think.

One of the healthiest things the new Euro-MPs could do would be to increase the investigative activities of the committees through — as often mooted — more public hearings of experts and interest groups, and by seeing for themselves whether, for example, peasants, the unemployed, or the poor of decaying inner cities are in greater need of community funds. They will find that the Brussels bureaucracy is, for all its faults, more open, more flexible and less desk-bound than Whitehall. One of my own hopes is that they will find ways — pending the acquisition of greater powers — of teaching national parliaments a lesson or two about how to open up the machinery of government. That, coupled with a greater understanding of other countries' problems, would be a substantial contribution.

Previous page

Previous page