WHERE THERE'S A WILL . . .

Edward Whitley investigates what Jacob Rothschild is

doing with Britain's largest inheritance - and the tax he must pay on it

ON THE death of a distant — very distant — cousin in December 1988, Jacob (now Lord) Rothschild inherited the bulk of the largest will ever made in this country some £76 million from an estate worth £96 million. He also inherited the largest in- heritance tax liability the Inland Revenue has ever invoiced, estimated at £30 million. Over the past year and a half Jacob has been exploring the frontiers of tax law in an attempt to utilise the inheritance tax bill to his best advantage. The battle with the Inland Revenue is being played on Jacob's home territory, the art world, and the manoeuvrings of both sides can best be described in terms of art — rococo and baroque are words that spring to mind.

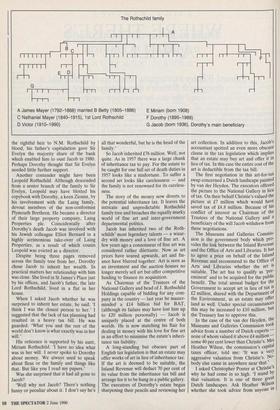

To understand the story it is necessary to traverse the breadth of the Rothschild family tree, and to try to elicit a

straightforward re- sponse from anyone in the fine art world and to poke into the four gov- ernment departments who are currently dis- puting how to account for the tax windfall.

The story of the money starts in the Probate Department of Somerset House. In the hushed atmos- phere of a library faded notices stipulate that brief notes may be taken 'in pencil only'. Most of the desks are occupied by disappointed ladies in tweed skirts who are grimly noting down the misplaced succes- sion of coveted silver tea services and fur coats.

Dorothy Rothschild made her last will in January 1988, aged 92. She added four codicils before her death in December. As Well as Jacob three other cousins are beneficiaries — Charlotte Rothschild was to inherit £50,000, Mrs Roszika Parker (daughter of Jacob's aunt Miriam Roth- schild) £25,000 and her younger sister £5,000. In the third codicil in November 1988, the Hanadiv Foundation, a Zionist charity established by Dorothy, was up- graded from £12 million to £20 million. In the final codicil seven days later Charlotte Rothschild was downgraded from £50,000 to £25,000. It is difficult to imagine what Charlotte would have done in that week to prompt the old lady to travel across Lon- don to change her will again. In each codicil her faint handwriting becomes progressively shakier. They are witnessed by two big round female signatures — A. Bilert, Secretary, and Juliet Miller, Arti- cled Clerk.

A month later Dorothy Rothschild died. The entire Rothschild family found out that they had all been skipped over in favour of Jacob. He inherited the responsi- bility for running Waddesdon Manor, the National Trust house originally owned by Dorothy's husband, her charitable trusts and £76 million worth of investments and works of art.

The history of this money becomes clear only by close examination of the Roth- schild family tree. Dorothy inherited £18 million from her husband Jimmy in 1957 at that time again the largest British will With no children the future of Dorothy's wealth was difficult to predict. There were a number of preten- ders to the inheritance. She had direct nephews and nieces, but according to Miriam Rothschild these were discarded as they lived in France and she wanted to leave her money in England.

The English Rothschilds divide into the camps of two cousins. One family, led by Sir Evelyn, runs N.M. Rothschild, the merchant bank. This is the junior branch — Sir Evelyn is the son of Anthony, the youngest son of Leopold who was the youngest brother of the first Lord Roth- schild. After the second world war Sir Evelyn's father, Anthony, dispossessed Jacob's father, the late Lord Rothschild, of his share in the bank. Although Jacob was the rightful heir to N.M. Rothschild by blood, his father's capitulation gave Sir Evelyn the majority share of the bank which enabled him to oust Jacob in 1980. Perhaps Dorothy thought that Sir Evelyn needed little further support.

Another contender might have been Leopold Rothschild. Although descended from a senior branch of the family to Sir Evelyn, Leopold may • have blotted his copybook with Dorothy, a keen Zionist, by his involvement with the Laing family, devout members of the non-conformist Plymouth Brethren. He became a director of their large property company, Laing Properties plc. Coincidentally after Dorothy's death Jacob was involved with his Jewish colleague Elliot Bernard in a highly acrimonious take-over of Laing Properties, as a result of which cousin Leopold was evicted as a director.

Despite being three pages removed across the family tree from her, Dorothy chose Jacob to inherit her wealth. In practical matters her relationship with him was close. She lived in St James's Place just by his offices, and Jacob's father, the late Lord Rothschild, lived in a flat in her house.

When I asked Jacob whether he was surprised to inherit her estate, he said, 'I think I was the closest person to her.' I suggested that the lack of tax planning had resulted in a heavy tax bill. He was guarded. 'What you and the rest of the world don't know is what exactly was in her will.'

His reticence is supported by his aunt, Miriam Rothschild. 'I have no idea what was in her will. I never spoke to Dorothy about money. We always used to speak about fleas or the family and things like that. But like you I read my papers.'

Was she surprised that it had all gone to Jacob?

`Well why not Jacob? There's nothing funny or peculiar about it. I don't say he's all that wonderful, but he is the head of the family.'

So Jacob inherited £76 million. Well, not quite. As in 1957 there was a large chunk of inheritance tax to pay. For the estate to be caught for one full set of death duties in 1957 looks like a misfortune. To suffer a second set looks like carelessness — and the family is not renowned for its careless- ness.

The story of the money now diverts to the potential inheritance tax. It leaves the intricate and unpredictable Rothschild family tree and broaches the equally murky world of fine art and inter-government departmental politics. Jacob has inherited two of the Roth- schilds' most legendary talents — a wizar- dry with money and a love of fine art. A few years ago a connoisseur of fine art was considered rather dilettante. Now as art prices have soared upwards, art and fin- ance have blurred together. Art is seen as an investment and the auction houses no longer merely sell art but offer competitive funding to finance its acquisition. As Chairman of the Trustees of the National Gallery and head of J. Rothschild Holdings capable of bidding for any com- pany in the country — last year he master- minded a £14 billion bid for BAT, (although its failure may have lost him up to £20 million personally) — Jacob is uniquely placed at the centre of both worlds. He is now matching his flair for dealing in money with his love for fine art in an effort to minimise the estate's inheri- tance tax liability.

A long-standing but obscure part of English tax legislation is that an estate may offer works of art in lieu of inheritance tax. If the art is deemed to be suitable, the Inland Revenue will deduct 70 per cent of its value from the inheritance tax bill and arrange for it to be hung in a public gallery. The executors of Dorothy's estate began sharpening their pencils and reviewing her art collection. In addition to this, Jacob's accountant spotted an even more obscure clause in the tax legislation which implies that an estate may buy art and offer it in lieu of tax. In this case the entire cost of the art is deductible from the tax bill.

The first negotiation in this art-for-tax swap concerned a Dutch landscape painted by van der Heyden. The executors offered the picture to the National Gallery in lieu of tax. On their behalf Christie's valued the picture at £7 million which would have saved tax of £4.8 million. Because of his conflict of interest as Chairman of the Trustees of the National Gallery and a beneficiary of the will Jacob withdrew from these negotiations.

The Museums and Galleries Commis- sion is the government body which pro- vides the link between the Inland Revenue and the Office of Arts and Libraries. It has to agree a price on behalf of the Inland Revenue and recommend to the Office of Arts and Libraries whether the art is suitable. The art has to qualify as 'pre- eminent' and to be acquired for the public benefit. The total annual budget for the Government to accept art in lieu of tax is £2 million, shared with the Department of the Environment, as an estate may offer land as well. Under special circumstances this may be increased to £10 million, but the Treasury has to approve this. In the case of the van der Heyden, the Museums and Galleries Commission took advice from a number of Dutch experts --- none of whom valued it above £4 million --- some 40 per cent lower than Christie's. Mrs Heather Wilson, the commission's capital taxes officer, told me: 'It was a very aggressive valuation from Christie's. No- body else came in anywhere near that. ,

I asked Christopher Ponter at Christie s why he had come in so high. stand by that valuation. It is one of three great Dutch landscapes. Ask Heather Wilson i whether she took advice from anyone in the trade rather than just academics at art galleries.'

I asked Heather Wilson. 'I try to avoid the trade. You never know what other side deals they have between themselves,' she said.

I tried a few people in the art world but as soon as I mentioned my interest in the Rothschilds the excuses began.

'Ask Charles Truman — he's your man.' 'I'm afraid I can't help. Ask Timothy Clifford.'

'Give Michael Kitson a ring.'

'Ask Heather Wilson — but don't say I told you.'

'Try Neil Macgregor.'

'Geoffrey de Belaigue.'

Eventually Anna Somers-Cocks, editor of the art magazine Apollo, enlightened me. 'People in the art world just don't talk about the Rothschilds to outsiders.'

Without mentioning the Rothschilds I asked a Dutch expert at Sotheby's about the van der Heyden.

'Frankly rather a dull picture.'

'Would you have valued it at £7 million?' 'No. That was very toppish.'

'Is it a "pre-eminent" picture?

'Well, you might not think so from walking around the gallery.'

Such are the niceties of the art world that the negotiations lasted over a year. Even- tually the value of the picture was agreed at £4 million and the National Gallery announced that they were 'astounded and staggered' by the acquisition. Jacob had saved £2.8 million of inheritance tax exceeding the Government's £2 million budget for all art to be accepted in lieu of tax in 1989.

A useful benefit from these negotiations is that while an offer of art for tax is being discussed, the interest on the potential inheritance tax clocks up to the benefit of the estate rather than — as is normally the Case when there is a delay in payment of inheritance tax —.to the benefit of the Inland Revenue. As well as saving tax of £2.8 million, by the time the picture was installed in the National Gallery Jacob had earned interest in the region of £700,000. The next art-tax swap was even more daring. Jacob offered an ingenious solution to the vexed question of the sale of Canova's Three Graces to the Paul Getty Museum. As the Government was being criticised for failing to prevent the export of another important work of art, Jacob proposed a solution. He would be amen- able to the Government using £7.6 million of his Inheritance Tax bill to buy the Three Graces. There was some speculation that the statue would then stand at Waddesdon Manor, the National Trust house run by Jacob since Dorothy's death, but Jacob did not attach any conditions to the offer. Indeed, as the National Trust only applies for art which shares a history with the house it would not apply for the Three Graces to be housed at Waddesdon. If Jacob's offer is accepted, the Three Graces will probably go to the National Gallery.

The problem is that as Dorothy Roth- schild's estate has to own the statue in order to offer it in lieu of tax, the Govern- ment has to agree to the scheme before- hand. If Jacob went ahead and bought the Three Graces without government approv- al, he might end up owning three naked ladies who, whatever they might do for his artistic taste buds, would do little for his Inheritance Tax problem.

If Jacob's offer is successful, the sequ- ence of cash transfers would be as follows: Dorothy Rothschild's estate would pay £7.6 million to a Cayman Islands registered company called Fine Art Investment and Display Limited. Nobody knows the be- neficial owner of this company and thus who will enjoy the £7.6 million. No doubt the Inland Revenue will follow the money to the Cayman Islands.

The estate would then pass the statue to the Inland Revenue in exchange for a £7.6 million deduction from their inheritance tax bill. With little use for it the Inland Revenue would sell the statue for £7.6 million to the Office of Arts and Libraries who would allocate it to a suitable venue. The Office of Arts and Libraries would be reimbursed by the Treasury. The Inland Revenue would consolidate the £7.6 mil- lion into its accounts where it would be passed back to the Treasury. The only loser in this virtuous circle of cash transfers is the Treasury who would otherwise have received £7.6 million cash.

Jacob Rothschild apparently stands to gain nothing from this, apart from the satisfaction of utilising his cousin's inheri- tance tax bill to save a work of art for the country. But his position in the art world will be greatly enhanced accordingly (in the same way as he gained nothing but prestige from hosting the recent meeting between President Mitterrand and Mrs Thatcher at Waddesdon). If this scheme fails, and his offer has been matched by a private offer from the Barclay brothers, Jacob has offered to extend it to any sufficiently important works of art which come on to the market in the future.

But the Government has not given Jacob any clear indication whether they want him to do this or not. None of the four departments who need to administer his proposal has confirmed whether the scheme is acceptable. Perhaps they suffer from the same paralysis in dealing with the Rothschilds as the fine art world. In the meantime, until they make up their minds they— or rather the Treasury — are losing considerable amounts of money.

While Jacob's offer of £7.6 million re- mains open, the interest on this potential inheritance tax accrues to the benefit of the estate rather than the Inland Revenue. The £7.6 million is currently earning some £700,000 a year. Even if the scheme eventually fails, it appears Jacob will have earned a large amount of money on the back of money which would otherwise have been in the Treasury's coffers all along. This is the Government's responsi- bility rather than any cynical intention of Jacob's. However, it does exhibit the supreme Rothschild banking skills — the ability to make a fortune out of other people's money. And this time it is without even trying — it is courtesy of the Inland Revenue. How Nathaniel Mayer Roth- schild, the founder of the family's fortunes, would have laughed.

'I married the girl next door, which gives you an idea of the kind of neighbourhood I'm from.'

Previous page

Previous page