Dance

Torvill and Dean (Earl's Court Exhibition Centre, till 10 June)

Revolution on ice

Deirdre McMahon

In the opening moments of Bolero, Jayne Torvill and Christopher Dean kneel on the ice, facing each other at angles. As Ravel's seductive rhythms begin, their bodies response rapturously to the music, swaying backwards and forwards, embrac- ing briefly and drawing apart. Dean then lifts Torvill's outstretched body into his arms and turns her gently over his shoul- der. During the rest of the dance their bodies weave sinuous patterns of curves and arches. The tension and power build up inexorably until that final tremendous climax when the two skaters suddenly collapse on the ice. Bolero is one of the most erotic pieces of British choreography to be created over the last decade. It features in the new show at Earl's Court and after six years its spell is undimmed.

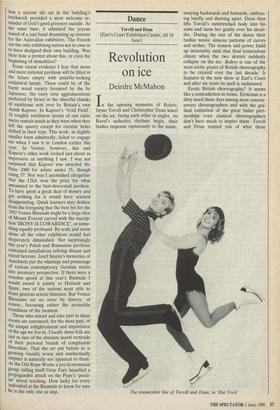

Erotic British choreography? It seems like a contradiction in terms. Eroticism is a dirty word these days among most contem- porary choreographers and with the gra- dual extinction of the great ballet part- nerships even classical choreographers don't have much to inspire them. Torvill and Dean remind you of what those The immaculate line of Torvill and Dean, in Rat Trick' partnerships were like, but even in the early Eighties their skating was also re- markable for qualities that were beginning to disappear from British classical dancing: their immaculate line, the vivid clarity of their upper bodies and their lyrical musi- cality. All these qualities were fused together in dances like Mack and Mabel and the famous Matador paso doble which distilled drama, wit and emotion into the space of a few short minutes.

The partnership looks so right when one watches them but they have worked hard and with considerable shrewdness to dis- guise some of their handicaps. Dean is slim and elegant but Torvill is ten inches smaller and can sometimes look chunky beside him. In his choreography Dean made her move more expansively, in long, slow, luxuriating phrases, most memorably in Summertime, in which she also radiated allure. If you look at some of those incredibly dowdy photographs of them earlier in their careers, allure is the last word you would use to describe them.

Although Torvill and Dean went pro- fessional after the 1984 Olympics, the shock of the revolution which they brought about in ice dancing is still being absorbed. Nowhere was this more true than in the area of music, where skating generally was notorious for its insensitive and jarring conjunctions of different scores: scratchy cha-chas tacked on to Rachmaninov's Second Piano Concerto — that sort of thing. Torvill and Dean introduced the unitary score in Mack and Mabel, but watching the recent championships I was disappointed to see how few skaters had followed their example. Their work still looks revolutionary.

One of the big problems for champion skaters turning professional has been how to move from the fairly rigorous restric- tions of competition to the demands of ice entertainment. In the late 1970s John Curry raised the artistic standards of professional skating and commissioned works from choreographers such as Twyla Tharp, Ken- neth MacMillan and Robert Cohan. The results were variable mainly because figure skating, for all Curry's efforts, is still obstinately hooked on virtuoso effects and is thus rather inexpressive. The partnership of Torvill and Dean, with its sense of theatre, is probably better suited to profes- sional skating than either Curry or Robin Cousins.

In their new show at Earl's Court Torvill and Dean appear with the Russian All- stars. The choreographic honours are di- vided between Dean and Tatiana Tarasova who was, coincidentally, the trainer of Bestemianova and Bukin, eternal runners- up to the British couple in the early 1980s. There is a discrepancy in style and quality between Dean and Tarasova. Tarasova's brassy Samba has a pounding, unsubtle beat and in a sense represents everything that Torvill and Dean reacted against. On the other hand, her Polovtsian Dances from Prince Igor have great panache. In some of the big numbers like Ragtime and Hollywood Dean demonstrates that he can do ensemble pieces as well, helped by a very canny musical ear. Ragtime uses some of the orchestrations for MacMillan's Elite Syncopations, while Hollywood has Her- shy Ray's Gershwin arrangements for Balanchine's scintillating Who Cares? In the new Torvill and Dean numbers, parti- cularly Missing and Akhnaton, they are continuing to experiment with restricted metrical rhythms (as in Bolero) in order to exploit greater shading and texture in their movement. I wish they were still compet- ing so that we could see these pieces more often and appreciate their subtlety which is rather lost in a big space like Earl's Court.

Their setting of John Lennon's 'Imagine' is, I think, the best number in the show. Clad in white silk shirts and stylish black trousers, they create a quietly sensational effect. At moments her body seems to melt into his, when she swirls away across the ice, eternally elusive. Magic.

Previous page

Previous page