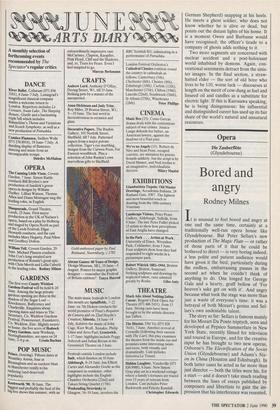

Cinema

Dreams (`PG', Lumiere)

Image problems

Hilary Mantel

Words fail us, constantly. Akira Kurosawa has said that if the message of his films could be put into words he would take the cheap way out — write it on a placard and carry it around with him. Even in the world of images, there is likely to be a shortfall between the film-maker's vision and the audience's reality. You try to transplant an image from brain to brain, but technical problems get in the way, and scarcity of talent and money. Kurosawa has accepted fewer compromises than most directors. His perfectionism is legendary. When he made Ran, his Japanese rework- ing of King Lear, he would keep his cast and crew on standby for days at a time, disregarding the expense, until the weather changed to his liking.

He is 80 now, and after 28 films takes on the greatest image-transplantation chal- lenge — his own dreams. The eight seg- ments which make up this film represent the nightmares and reveries of various stages in life; some have a genuine whiff of the terrors of the subconscious. Some are studied and deliberate — the correct and useful dreams one would like to have, with music and choreography all in place. In each case, the images are more fluent and significant than the words which accom- pany them. Dreams should be seen for the exercise that it gives the imagination, not for its thumping didactic content.

In the first segment, 'Sunshine through the Rain', a little boy ventures into a forest where the ground hisses and steams and the trees dwarf him. He witnesses a forbid- den spectacle — the foxes' wedding proces- sion. The foxes, represented by human dancers, are sedate and minatory, curious- ly substantial to the western eye. Later a fox calls at his home, and leaves the spying child a knife with which to kill himself. There is a premonitory chill in the flash of the blade — though Kurosawa's 1971 suicide attempt is likely to have had more to do with the state of the Japanese film industry than with vulpine wrath.

In 'The Peach Orchard' the director shows his concern for the natural world: `Peaches can be bought. But where can you buy a whole orchard in bloom?' The episode ends in a blizzard of petals; the next segment brings a real blizzard, as roped and laden figures clank onwards through a white-out, their laboured brea- thing louder than the muffled howling of the wind. We have all dreamt this one, waking or asleep; there are years when movement is so painful that it is easier to drop where you stand. The polar desert could be personal or ideological; this plea for endurance, for heroism, is most mov- ing. It is a pity that a sort of guardian angel figure appears, to cover the fallen explorer with what seems to be a length of lurex knitting. A more definite sense of the ridiculous emerges in 'Crows', a jaunty and naive fragment in which the Kurosawa figure steps into Van Gogh's paintings. Martin Scorsese makes an appearance as the artist — it is surely one of the comic turns of the year.

In another segment an army officer tramps through a tunnel, a ferocious dog (a

German Shepherd) snapping at his heels. He meets a ghost soldier, who does not know whether he is alive or dead, but points out the distant lights of his home. It is a moment Owen and Barbusse would have recognised; the officer's tirade to a company of ghosts adds nothing to it.

Two more segments are concerned with nuclear accident and a post-holocaust world inhabited by demons. Again, con- ventional sentiments detract from the sinis- ter images. In the final section, a straw- hatted elder — the sort of old bore who lives to be 110, worse luck — discourses at length on the merit of cow-dung as fuel and linseed oil and candles as a substitute for electric light. If this is Kurosawa speaking, he is being disingenuous: his influential and distinguished career has used up its fair share of the world's natural and unnatural resources.

Previous page

Previous page