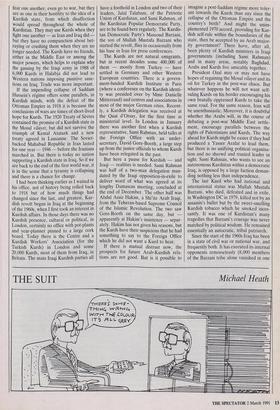

WHAT ABOUT THE KURDS?

David Adamson on the people

who are always left out of Middle East peace settlements

SARBAST Aram, co-ordinator of the Kurdish Cultural Centre in south London, was considering the imminent ending of the war and the likely demise of Saddam Hussein. 'I think we are back to where we were in 1918."Back to the Mosul vilayet?' I asked. It was there that it had seemed possible, very briefly, that the Kurds might be given a place of their own. 'Yes,' he said, 'it is like that, I think.'

The vilayet is the old Ottoman Turkish 'I'm terribly sorry — he's fully booked until the end of the year.' province in the north-east of Iraq, the heartland of a nationalist revolt whose origins go back to the first half of the 19th century and which, at different times, has affected most of the 600-mile arc of mountainous terrain known as Kurdistan. The Kurds are not a monolithic group by any means: they are divided by dialects and culture as well as by mountain ranges and frontiers. Even in London the indigent Kurmanji-speaking Kurds from Turkey do not associate with the relatively affluent and urban Sorani-speaking Iraqi Kurds. The largest and most populous — and poorest — part of the region is in Turkey. The rest is divided among Iran, Iraq and Syria (which has a small population of about one million Kurds). Around 300,000 live in the Soviet republic of Armenia, established by another race which got nothing out of the break-up of the Otto- man Empire.

There are no entirely reliable figures on the Kurdish population, but the Minority Rights Group believes it is about 21 million, the world's largest stateless minor- ity. They account for a fifth of Turkey's population and nearly a quarter of Iraq's. Turks, Arabs and Iranians may despise or fear one another, even go to war, but they are as one in their hostility to the idea of a Kurdish state, from which disaffection would spread throughout the whole of Kurdistan. They may use Kurds when they fight one another — as Iran and Iraq did but they have no compunction about bet- raying or crushing them when they are no longer needed. The Kurds have no friends, either in the Middle East or among the major powers, which helps to explain why the gassing by the Iraqi army in 1988 of 6,000 Kurds in Halabja did not lead to Western nations imposing punitive sanc- tions on Iraq. Trade was more important. If the impending collapse of Saddam Hussein's regime offers some parallels, in Kurdish minds, with the defeat of the Ottoman Empire in 1918 it is because the conclusions of wars are times of short-lived hope for Kurds. The 1920 Treaty of Sevres contained the promise of a Kurdish state in the Mosul vilayet, but did not survive the triumph of Kemal Ataturk and a new treaty agreed in Lausanne. The Soviet- backed Mahabad Republic in Iran lasted for one year — 1946 — before the Iranians marched in. But there is today no nation supporting a Kurdish state in Iraq. So if we are back to the end of the first world war, it is in the sense that a tyranny is collapsing and there is a chance for change.

I had been thinking earlier as I waited in his office, not of history being rolled back to 1918 but of how much things had changed since the last, and greatest, Kur- dish revolt began in Iraq at the beginning of the 1960s, when I first took an interest in Kurdish affairs. In those days there was no Kurdish presence, cultural or political, in London, certainly no office with pot-plants and year-planner pinned to a large cork board. Today there is the Centre and a Kurdish Workers' Association (for the Turkish Kurds) in London and some 20,000 Kurds, most of them from Iraq, in Britain. The main Iraqi Kurdish parties all have a foothold in London and two of their leaders, Jalal Talabani, of the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan, and Sami Rahman, of the Kurdistan Popular Democratic Party, are to be found here regularly. The Kurdis- tan Democratic Party's Massoud Barzani, the son of Mullah Mustafa Barzani who started the revolt, flies in occasionally from his base in Iran for press conferences.

The Kurds are not natural emigrants, but in recent decades some 400,000 of them — mostly from Turkey — have settled in Germany and other Western European countries. There is a govern- ment-funded Kurdish Institute in Paris (where a conference on the Kurdish identi- ty was presided over by Mme Danielle Mitterrand) and centres and associations in most of the major German cities. Recent- ly, a Kurdish delegation was received at the Quai d'Orsay, for the first time at ministerial level. In London in January there was another first when a Kurdish representative, Sami Rahman, held talks at the Foreign Office with an under- secretary, David Gore-Booth, a large step up from the junior officials to whom Kurds have been relegated in the past.

But here a pause for Kurdish — and Iraqi — realities is needed. Sami Rahman was half of a two-man delegation man- dated by the Iraqi opposition-in-exile to deliver word of what was agreed at its lengthy Damascus meeting, concluded at the end of December. The other half was Abdul Assiz Hakim, a Shi'ite Arab Iraqi, from the Teheran-based Supreme Council of the Islamic Revolution. The two saw Gore-Booth on the same day, but apparently at Hakim's insistence — separ- ately. Hakim has not given his reasons, but the Kurds have their suspicions that he had something to say to the Foreign Office which he did not want a Kurd to hear.

If there is mutual distrust now, the prospects for future Arab-Kurdish rela- tions are not good. But is it possible to imagine a post-Saddam regime more toler- ant towards the Kurds than any since the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and the country's birth? And might the unim- plemented 1970 accord, providing for Kur- dish self-rule within the boundaries of the state, then be accepted by an Arab major- ity government? There have, after all, been plenty of Kurdish ministers in Iraqi governments (including Sami Rahman) and in many areas, notably Baghdad, Arabs and Kurds live amicably together.

President Ozal may or may not have hopes of regaining the Mosul vilayet and its oil for Turkey in the post-war chaos. But whatever happens he will not want self- ruling Kurds on his border encouraging his own brutally oppressed Kurds to take the same road. For the same reason, Iran will be unenthusiastic. Moreover, it is doubtful whether the Arabs will, in the course of debating a post-war Middle East settle- ment, encourage parallels between the rights of Palestinians and Kurds. The way ahead for Kurds might be easier if they had produced a Yasser Arafat to lead them, but there is no unifying political organisa- tion and no shrewd and trusted leader in sight. Sami Rahman, who wants to see an autonomous Kurdistan within a democratic Iraq, is opposed by a large faction deman- ding nothing less than independence.

The last Kurd who had national and international status was Mullah Mustafa Barzani, who died, defeated and in exile, in Washington DC in 1979, killed not by an assassin's bullet but by the sweet-smelling Kurdish tobacco which he smoked inces- santly. It was one of Kurdistan's many tragedies that Barzani's courage was never matched by political wisdom. He remained essentially an autocratic, tribal patriarch.

Since the start of the 1960s Iraq has been in a state of civil war or national war, and frequently both. It has executed its internal opponents remorselessly (8,000 members of the Barzani tribe alone vanished in one day in 1983, never to be seen again), become a centre for international terror- ism, invaded two of its neighbours in the world's richest oil-bearing region, de- veloped and used chemical weapons and done its best to make nuclear weapons.

While the kind of government post- Saddam Iraq gets is clearly not something which the allies will regard as a domestic issue, the future for the Kurdish people is something which Iraq's Arabs and Kurds will have to work out for themselves. All the West can do is encourage a system of government in which the rights of a minor- ity are accepted and protected, a task which may prove harder than getting Sad- dam Hussein out of Kuwait. Sadly, the chances are that, once again, whoever wins the peace in the region, the Kurds will lose.

David Adamson is the author of The Kurdish War.

Previous page

Previous page