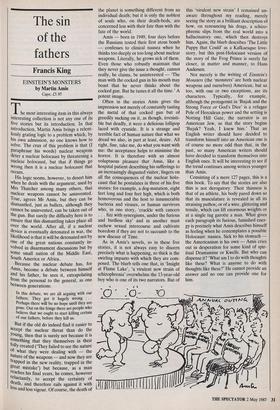

The sin of the fathers

Francis King

EINSTEIN'S MONSTERS by Martin Amis Cape, £5.95 The most interesting item in this always interesting collection is not any one of its five stories but its introduction. In that introduction, Martin Amis brings a relent- lessly grating logic to a problem which, by his own admission, no one knows how to solve. The crux of this problem is that (I paraphrase his words) nuclear weapons deter a nuclear holocaust by threatening a nuclear holocaust, but that if things go wrong then it is a nuclear holocaust that occurs.

His logic seems, however, to desert him when he deals with the argument, used by Mrs Thatcher among many others, that nuclear weapons cannot be uninvented. True, agrees Mr Amis, but they can be dismantled, just as bullets, although they cannot be uninvented, can be taken out of the gun. But surely the difficulty here is to ensure that this dismantling takes place all over the world. After all, if a nuclear device is eventually detonated in war, the likelihood is that it will be detonated not by one of the great nations constantly in- volved in disarmament discussions but by some small nation of the Middle East, South America or Africa.

Because the nuclear debate has, for Amis, become a debate between himself and his father, he sees it, extrapolating from the personal to the general, as one between generations:

In this debate, we are all arguing with our fathers. They got it hugely wrong . . . Perhaps there will be no hope until they are gone. Out on the fringe there are people who believe that we ought to start killing certain of our fathers, before they kill us.

But if the old do indeed find it easier to accept the nuclear threat than do the Young, then that is surely not because it is something that they themselves in their folly created (`They failed to see the nature of what they were dealing with — the nature of the weapons — and now they are trapped in the new reality, trapped in the great mistake') but because, as a man reaches his final years, he comes, however reluctantly, to accept the certainty of death, and therefore rails against it with less and less vigour. Of course, the death of the planet is something different from an individual death; but it is only the noblest of souls who, on their death-beds, are concerned less with their fate than with the fate of the world.

Amis — born in 1949, four days before the Russians tested their first atom bomb — confesses to clinical nausea when he thinks too deeply or too long about nuclear weapons. Literally, he grows sick of them. Even those who robustly maintain that they never give the issue a thought, cannot really, he claims, be uninterested — 'The man with the cocked gun in his mouth may boast that he never thinks about the cocked gun. But he tastes it all the time.' A potent image.

Often in the stories Amis gives the impression not merely of constantly tasting the metal of that cocked gun but of greedily sucking on it, as though, irresisti- ble but deadly, it were a delicious lollipop laced with cyanide. It is a strange and terrible fact of human nature that what we dread we also, in part at least, desire. All right, fine, take me, do what you want with me: the acceptance helps to minimise the horror. It is therefore with an almost voluptuous pleasure that Amis, like a hospital patient describing his sufferings to an increasingly disgusted visitor, lingers on all the consequences of the nuclear holo- caust that he postulates in three of his five stories: for example, a dog-mutation, eight feet long and four feet high, which is both homovorous and the host to innumerable bacteria and viruses, or human survivors who, in one story, 'crackle with cancers . . fizz with synergisms, under the furious and birdless sky' and in another must eschew sexual intercourse and cultivate boredom if they are not to succumb to the new disease of Time.

As in Amis's novels, so in these five stories, it is not always easy to discern precisely what is happening, so thick is the swirling impasto with which they are com- posed. The blurb tells one that, in 'Insight at Flame Lake', 'a virulent new strain of schizophrenia' overwhelms the 13-year-old boy who is one of its two narrators. But of this 'virulent new strain' 1 remained un- aware throughout my reading, merely seeing the story as a brilliant description of how, on renouncing his drugs, a schizo- phrenic slips from the real world into a hallucinatory one, which then destroys him. Again, the blurb describes 'The Little Puppy that Could' as a Kafkaesque love- story, but this post-Holocaust version of the story of the Frog Prince is surely far closer, in matter and manner, to Hans Andersen.

Not merely is the writing of Einstein's Monsters (the 'monsters' are both nuclear weapons and ourselves) American, but so too, with one or two exceptions, are its characters. Typically, for example, although the protagonist in `Bujak and the Strong Force or God's Dice' is a refugee Pole of Herculean power and the setting is Notting Hill Gate, the narrator is an American Jew, so that the story begins `Bujak? Yeah, I knew him.' That an English writer should have decided to transform himself into an American one is of course no more odd than that, in the past, so many American writers should have decided to transform themselves into English ones. It will be interesting to see if the trend continues among writers younger than Amis.

Consisting of a mere 127 pages, this is a thin book. To say that the stories are also thin is not derogatory. Their thinness is that of an athlete, his body pared down so that its musculature is revealed in all its straining pathos; or of a wire, glittering and tensile, which can lift enormous weights or at a single tug garotte a man. What gives each paragraph its furious, famished ener- gy is precisely what Amis describes himself as feeling when he contemplates a possible Holocaust: nausea. Sick to his stomach the Americanism is his own — Amis cries out in desperation for some kind of spir- itual Dramamine or Kwells. But who can dispense it? 'What am Ito do with thoughts like these? What is anyone to do with thoughts like these?' He cannot provide an answer and no one can provide one for him.

Previous page

Previous page