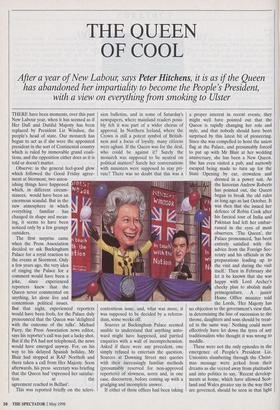

THE QUEEN OF COOL

has abandoned her impartiality to become the People's President, with a view on everything from smoking to Ulster

THERE have been moments, over this past New Labour year, when it has seemed as if Her Dull and Dutiful Majesty has been replaced by President Liz Windsor, the people's head of state. Our monarch has begun to act as if she were the appointed president in the sort of Continental country which is ruled by immovable grand coali- tions, and the opposition either does as it is told or doesn't matter.

Observe: in the general feel-good glow which followed the Good Friday agree- ment at Stormont, two aston- ishing things have happened which, in different circum- stances, would have been an enormous scandal. But in the new atmosphere in which everything familiar has changed its shape and mean- ing, it seems to have been noticed only by a few grumpy outsiders.

The first surprise came when the Press Association decided to ask Buckingham Palace for a royal reaction to the events at Stormont. Only a few years ago, the very idea of ringing the Palace for a comment would have been a joke, since experienced reporters knew that the Queen never commented on anything, let alone live and contentious political issues. But that night, experienced reporters would have been fools, for the Palace duly pronounced that the Queen was 'delighted with the outcome of the talks'. Michael Parry, the Press Association news editor, says his reporter's call was just a lucky shot. But if the PA had not telephoned, the news would have emerged anyway. For, on his way to his delayed Spanish holiday, Mr Blair had stopped at RAF Northolt and there taken a call from Her Majesty. Soon afterwards, his press secretary was briefing that the Queen had 'expressed her satisfac- tion at the agreement reached in Belfast'.

This was reported briefly on the televi- sion bulletins, and in some of Saturday's newspapers, where mainland readers possi- bly felt it was part of a wider chorus of approval. In Northern Ireland, where the Crown is still a potent symbol of British- ness and a focus of loyalty, many citizens were aghast. If the Queen was for the deal, who could be against it? Surely the monarch was supposed to be neutral on political matters? Surely her conversations with ministers were supposed to stay pri- vate? There was no doubt that this was a contentious issue, and, what was more, it was supposed to be decided by a referen- dum, some weeks off.

Sources at Buckingham Palace seemed unable to understand that anything unto- ward might have happened, and parried enquiries with a wall of incomprehension. Asked if there were any precedent, one simply refused to entertain the question. Sources at Downing Street met queries with their increasingly familiar methods (presumably reserved for non-approved reporters) of slowness, scorn and, in one case, discourtesy, before coming up with a grudging and incomplete answer.

If either of these offices had been taking These were not the only episodes in the emergence of People's President Liz. Unionists slumbering through the Christ- mas message were jerked from their dreams as she veered away from platitudes and into politics to say, 'Recent develop- ments at home, which have allowed Scot- land and Wales greater say in the way they are governed, should be seen in that light and as proof that the kingdom can still enjoy all the benefits of being united.' Unlike her Ulster pronouncement, this came some months after voting was over, but it seemed to endorse the controversial government view that devolution strength- ened the Union. Then, on a rather relaxed and informal visit to Keswick School in Cumbria, she plunged into a different sort of non-impartiality, aiming a royal swipe at all her smoking subjects. 'Cigarettes are nasty things,' she told the pupils, in a remark that was pure New Labour, and was halfway round the world in hours. In an instant, the monarchy was ranged on the side of the health-fetishist faction. This may be technically non-political, but it would be interesting to see what hap- pened if she warned schoolchildren against male homosexuality, also a grave risk to health.

Ben Pimlott, the Queen's biographer, says this sort of thing is one of the pitfalls of the post-Diana informality which the Palace has embraced. 'Once you leave the language of cliché, you rapidly fall into dif- ficulties,' he warns. But Professor Pimlott, a friend of the government, does not think it is any more serious than that. To support his view, he points out that the Queen has Walked into controversy before. In October 1972, she infuriated opponents of the Com-

mon Market by saying that British entry was 'a great achievement'. Then, at her 1977 silver jubilee, she angered Welsh and Scottish nationalists with words that seem to contradict her Christmas message 20 years later, and also her delight at the Ulster agreement: cannot forget that I was crowned Queen of the United King- dom of Great Britain and Northern Ire- land. Perhaps this jubilee is the time to remind ourselves of the benefits which union has conferred, at home and in our international dealings, on the inhabitants of all parts of this United Kingdom.' The 1977 speech, interestingly, is supposed to have been made entirely on her initiative, though the government did not object when shown the text.

Even so, there are sharp and important differences between these episodes and the new style. You could argue that entry to the Common Market was a great achieve- ment of diplomacy, whether you liked it or not. Some even suspect that the words were wrung out of the palace by the Heath government, to quash rumours that the Queen was a secret opponent of Brussels, in which case they look pretty grudging. And, at the time, no referendum was envis- aged. This is rather different from volun- teering delight at the outcome of Stormont, when that outcome was a mass release of

convicts and a loosening of Ulster's bonds with the United Kingdom and has still to be voted on. Her 1977 pro-Union speech ran against the Callaghan government's plans for devolution and upheld the status quo. Her post-Stormont statements have plainly helped the government, and just as plainly weakened the status quo. The other differ- ence between then and now is that in the 1970s there were serious protests about her words. In today's brain-dead polity, there have been none to speak of.

The most haunting precedent, involving the Queen's father George VI, is not a happy one. That King invited Neville Chamberlain to bathe in applause on a floodlit Buckingham Palace balcony just after Munich. It was not the Windsors' finest hour, even if appeasement was then as popular as it is now. The embarrassment which followed probably helped the King to reconcile himself to Churchill, whom he had never liked, and to behave well during the war. Before our anti-smoking, devolv- ing, prisoner-releasin President gets sucked into campaigns for the single cur- rency, safe sex or anyt ;rig else, perhaps a little embarrassment would be in order from whoever is devising this new people's monarchy.

The author writes for the Express.

Previous page

Previous page