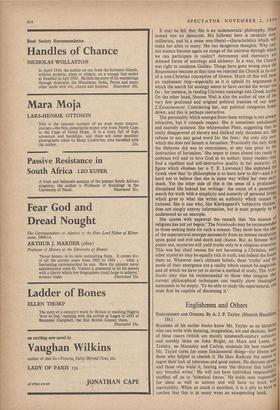

Englishmen and Others

READERS of his earlier books know Mr. Taylor as an historian who can. write with learning, imagination, wit and decision. Sortie of these essays (which are mainly nineteenth-century subjects) and notably those on John Bright, on Marx and Lenin, on Trotsky, on Macaulay and Carlyle, maintain his best standard Mr. Taylor cares for some fundamental things—for liberty and those who helped to cherish it. He likes Radicals but seems to regret their lack of tolerance and good nature. He distrusts power and those who wield it, fearing even 'the dictator that lurks any forceful writer.' He will not have individual responsibill tY shuffled off on to 'historical forces.' He holds men responsible for ideas as well as actions and will have no truck inevitability. When so much is excellent, it is a pity to have to confess that this is in many ways an exasperating book. Mr. Taylor alternates between two kinds of history—the highly specialised, narrative, political, and the unspecialised, universal, epigrammatic and paradoxical. In his first role, as an observer of the detailed behaviour of the political animal, he has few equals today. But he seems often to forget that man is several other kinds of animal as well and this makes his history less humane and wise than it might be. Like Ranke, he will ignore an aspect of life because it has no political significance, or dismiss the humanism of the Renaissance as 'incoherent,' choosing to be Interested in humanism only when it becomes, in eighteenth- century France, the basis df political theory and action and fits into the political jigsaw puzzle. History tends in this way to become a distillation of intellectualised politics. This is why he Is at his best in the nineteenth century, or when explaining how one thing followed another : at his weakest whenever his prejudices get the better of hint. An essay on Disraeli is spoilt by Irrelevant and unexplained vituperation against contemporary thinkers from whom he happens to differ. He can select for special Praise a passage by J. A. Hobson on imperialism for no better reason (as far as I can judge) than because it is a piece of conten- tious tub-thumping. He castigates the class dubbed 'respectable historians' for 'frowning on' Tom Paine, when in reality historians have for years been bending over backwards to do justice to Radicals of every kind.

The real trouble is that Mr. Taylor, like Cobbett (whom he admires) and other kindly men who enjoy a reputation for irascibility, cannot contain his impatience with the amiable virtues of those nearest to him socially and intellectually. This is a forgivable foible. The only danger is that it can turn into a Willingness to tolerate humbug provided it is remote or abstract enough not to constitute an immediate inconvenience. He lets the eat out of the bag in the paper on Bright, recalling how, as a Youthful aspirant for the Bright speaking prize ('in revolt as Usual against my surroundings') he looked for a subject which Would discredit Bright. The same trait still leads him into denunciations of the `establishment'—bishops, diplomats, The ones and those who read it—which become monotonous. Contrariwise, he puts his trust in the occupants of the public bar and their collective wisdom. The cult of pub wisdom is a harmless enough affectation in dons revolting against the senior common room or the Athenaeum. But to rest one's political judgements on the dogma that the more educated are always wrong and the less educated always right is nihilism not progress. Which people nYway? Only Englishmen, or others as well? Did the Germans In their beer gardens bear no responsibility for bringing Hitler to Power? Or Italians for keeping Mussolini in power? Who sup- ported Joseph McCarthy? Was appeasement the fault only of the so-called 'leaders,' politicians and diplomats? Belief in the virtues of the common man is well enough, provided it does not turn into the heresy of inverted snobbery : to pretend that men in the mass are more insulated against the follies of ignorance, hear or idleness, against the lust after power itself, than the mem- h,?rs of the Diplomatic Corps or the Bench of Bishops is romantic Iallsion. Mr. Taylor has an admonition for his readers : 'Every- kWio can have his private tastes, but they have no place in historical study.' It is difficult to think that he has sufficiently pondered the IMPlications of his own doctrine. •

CHARLES WILSON

Previous page

Previous page