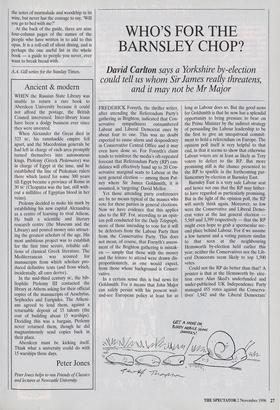

PROVINCIAL, PO-FACED POOTERISH

Also frightful, ridiculous and Puritanical;

that is what A.A. Gill thought about the Good Food Guide A SURVEY published last week claimed to prove that London was a better place for eating out in than Paris. When asked, the average business traveller said he'd rather get drunk in London than in Paris. But I suppose if you or I wanted to go out and sit surrounded by dandruff-covered, saggy-flannel-trousered men on expenses, entertaining each other with stories of how they had dinner in Paris last week and how it wasn't nearly as good as Quaglino's, then we might feel a little swelling of national pride. On the other hand, blowing yet another fanfare down the cornucopia of London's dinner tables is becoming embarrassing.

Just as Paris isn't representative of France, so London isn't representative of Britain. If the suits had been asked whether they'd rather eat out in Britain or in France, I imagine the answer would have been very different. As if to demon- strate how embarrassingly different Britain and France are in terms of eating out, a new edition of the Good Food Guide has just been published. It is exhaustively provincially comprehensive: no Copper Kettle or Betty's Bistro is too insignificant to get a gushing entry. The huge number of rustic doily-and-chocolate-surprise mer- chants make it virtually useless as an informed or informative directory. Its 600- odd pages hide the fact that outside Lon- don and a few London-patronised hotels, public eating in this country still has a very long way to go.

The Good Food Guide is now in its for- ties — and it sounds like it. It has matured into a ponderous committee man with Home Counties good taste who takes all his pleasures in moderation with smug self-satisfaction. Restaurants and, more importantly, their customers, have become more sophisticated in the last decade, but the Good Food Guide has not kept up with contemporary eating habits and has remained a balding, boring pedant, sitting in the lounge with a comforting schooner of something dry, going through the wine list looking for half-bottle bargains.

This wouldn't be important if the Good Food Guide didn't matter, but food guides make a difference to the restaurant busi- ness and can either spur or hinder progress. They are trusted, and the Good Food Guide is particularly trusted because it claims that it is completely independent: it carries no advertising, makes no charge for inclusion and is not beholden to out- side interests. Yet the Guide relies heavily on the public for its reviews and is thus beholden to every parsimonious retired solicitor with lavender notelets and a stamp.

Anyone who has received letters from the public will tell you that the sort of peo- ple who write letters are not, not to put too fine a point on it, the sort of people who write letters. They are not necessarily representative and they are rarely right. Ultimately, the proof of a guide is in the eating and, independent or not, the other guides are far more 'succulent and tasty' (to use the Good Food Guide's favourite words). The Good Food Guide is owned and run by the Consumer Association, that group of bearded and booted wor- thies so beloved of afternoon don't-put- your-head-in-the-fuse-box-son television programmes.

The Guide treats entertainment, hospitali- ty and gastronomy as if they were washing machines, lawnmowers and Teasmades. Cul- ture, community and civilisation are all just a matter of clean avocado-coloured suites, adequate avocado portions and a warm wel- come in the ingle-nook. The Guide is also deeply, lavishly and generously attached to adjectives and symbols. The adjectives are mostly robustly, toothsomely offered with a nestling garnish of inverted commas in a way which defies parody or constructive stylistic criticism.

The Caped Moral Crusader In these silent hieroglyphs you can find the true drip-dry-just-a-smidgen-merci des- iccated soul of this frightful work. The biggest, boldest symbol is not for any form of sybaritic pleasure — it's a cigarette with a cross through it. This is a guide ostensibly devoted to sensual pleasure that accords stopping people doing something its high- est accolade. It is obsessed with smoking in the trendy new consumer-sensitive way. One of the articles at the beginning of the Guide fumes, 'Would smoking restaurants be prepared to sell any wine on their list to non-smokers for £5, which is what a first growth claret is worth when wreathed in smoke?'

That is the true Pooterish whining of I- know-my-rights consumer-man. The rest of us have happily been eating, getting drunk, taking snuff, smoking pipes, cigars and hubble-bubbles, wearing harlot scent, laughing, lying, spitting and farting in restaurants for 200 years, without being told by the next table that we're muddying the top notes of the Château Talbot. This ridiculous po-faced Puritan tome is now demanding a discount for insufferable prigs. The Good Food Guide is a litany to the type that has learned everything and understands nothing, that lives a comfort- able, neat, supercilious life without ever being inquisitive or adventurous enough to discover the point of living.

If you read this guide as a book — and I don't recommend it — a weirdly familiar character swims before you on the pages, an identikit of a Home Counties English- man and his little woman• a self-satisfied Terry and June who motor to the saloon for little treats; a pair of middle-aged, mid- dle-brow, middle-income finger-waggers and change-jinglers who appreciate a hearty welcome from 'mine host' (the guide is slippery with dropped names: 'Janet per- forms miracles in the kitchen whilst Trevor is omnipresent with the glass that cheers').

Those who use the Guide want to eat in peace, live in peace, sleep in peace and die in peace. They know the value of money but not of a truffle. They check the knives for stains and each other's teeth for spinach. They like people who like them, and they think being broad-minded is all very well as long as it is understood that broad errs on the narrow side. They know that you have to complain to the top man. They write letters signed with adjectives, and they eat out because it gets her away from the stove and him away from the dish- cloth — and both away from each other.

Essentially, they appreciate food in restaurants as trophies of a quietly success- ful life, one of the little perks of being frugal and careful and keeping their public noses clean. They like to say, 'Oh yes, we've been there. A bit disappointing — lipstick on the glasses.' They talk a lot about things being civilised, but what they mean is a veal civili- sation — bland, bloodless, white, soft cul- ture that melts in your mouth and doesn't taste of much; a civilisation that searches for the notes of marmalade and woodchip in its wine, but never has the courage to say, 'Will you go to bed with me?'

At the back of the guide, there are nine four-column pages of the names of the people who have written in to add to this opus. It is a roll-call of silent dining, and is perhaps the one useful list in the whole book — a guide to people you never, ever want to break bread with.

A.A. Gill writes for the Sunday Times.

Previous page

Previous page