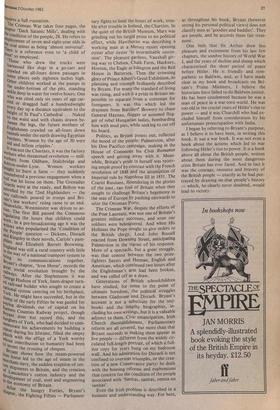

A book in my life

Harold Wilson

It has taken me a long time to decide on my choice of 'my favourite book'. For most of my summer holiday in the Isles of Scilly my choice fell on two American authors with a common subject, Bruce Catton and Carl Sandburg on the American Civil War. I have read these at least once a year since I first came across them. To take only Bruce Catton's account of the end of the fighting, down by the roadside near Appomattox Court House, with Sheridan and Ord waiting while a brown-bearded little man in mud-spattered uniform rode up. 'Is General Lee up there?', Grant asked. When Sheridan replied that he was, Grant said, 'Very well. Let's go up ... '. As the generals neared the end of their ride, a Yankee band in a field near the town struck up 'Auld Lang Syne'. Hence Catton's title: A Stillness at Ap- pomattox. Or Sandburg's last volume, end- ing with the burial of Lincoln at Oak Ridge:

'And the night came with great quiet.

And there was rest.

The prairie years, the war years, were over'.

Nevertheless, and not because of my pro- British prejudices, I have finally chosen that great historian and master of the English language, Sir Arthur Bryant. Again, to do justice to him would mean listing and en- thusing over his whole series covering Bri- tain's history from earliest times to the last World War. Britain has always been rich in historians, unique in its historians who in

addition to their strict adherence `-'3`,Icle honesty to the facts, display a literarY St, which illuminates beyond the events the' describe. I am fortunate in possessing, copies of almost all of his books, personal inscribed — in most cases making clearI own political standpoint by identify' himself as my 'Tory admirer'. Invidious though it is to select one of 11s works, my choice falls on one . spiration stems not from history alone but was aimed at a critical period of the 0131.' with the bombs falling nightly on BritaiArips cities and the Nazis poised to inV9"-. English Saga. English Saga covers just one century of the wider space he was covered over tilt years. Completed and published in 19,4° ,he reaches as far as the evacuation 01 'of Dunkirk beaches, and became a source inspiration to many of those who were co; pelled to read it in the dim light of can underground shelter — including, as :net testify, members of the War Cacoi secretariat. This year, I have found it usei ee to read it together with Sir Arthur's foft,hrd book, editing and commenting on 1-'`' Alanbrook's wartime diary. But his aP to is not to Britain as a nation at war: it is the Britain of the centuries. f the As a reporter of the 'Condition 0. People' issue, Marx gets one line less til7- Charles Booth, while Taine's description the poverty and squalor of Oxford Streela London Bridge, Haymarket and the Strail

The Crimean War takes four pages, the chapter 'Dark Satanic Mills', dealing with

the condition of the people, 28. He refers to the of seven and eight-year olds in tne coal mines as being 'almost universal'. There is a reference even to 'a child of three' so employed. Those who drew the trucks were harnessed like dogs in a go-cart and

crawled on all-fours down passages in

ether places only eighteen inches high. °,ther children worked at the pumps in the under-bottom of the pits, standing

ankle deep in water for twelve hours. One who was cited only six years of age car- ried or dragged half a hundredweight every day up a distance equivalent to the

height of St Paul's Cathedral ... Naked to the waist and with chains drawn be- tween the legs, the future mothers of Englishmen crawled on all-fours down tunnels under the earth drawing Egyptian burdens. Women by the age of 30 were old and infirm cripples.'

It was not the Chartists, it was the factory workers who threatened revolution — mill- workers from Oldham, Stalybridge and

,ksbton-under-Lyne. Women workers ;ciught to burn a farm — they suddenly benlenthered a previous engagement when a null was let loose on them. The Grenadier wards were at the ready, and Bolton was Patrolled by the 72nd Highlanders — the ew t railroads poured in troops and Bri- In's last workers' rising came to an end. Meanwhile, Westminster was driven to ac- tion. The first Bill passed the Commons regulating the hours that children could w7.1.K. In a pre-broadcasting age it was the the who popularised the 'Condition of PeoPle' question — Dickens, Disraeli "ud Kingsley in their novels, Carlyle's pam- rlets and Elizabeth Barrett Browning. itillgland was still a rural country with little 1-:,,ithe way of a national transport system to its communications together. :Yant's chapter, 'Iron Horse', records the 541. e.at social revolution brought by the ca„liwnYs. After the Stephensons it was e2Irge Hudson of York, linen-draper turn- nu railroad builder who sought to create a yational system centring on his birthplace, sh,cir``. He might have succeeded, but in the 0"In.P of the early Fifties he was gaoled for raYtng dividends out of capital on his vstern Counties Railway project, though Oant does hot record this, and the h.4ghers of York, who had decided to corn- s"'tenlorate his achievements by building a natue during his lifetime, filled the empty whnth With the effigy of a York worthy 95e contribution to humanity had been

to invent the crossing of cheques. irr,131"Yant 11 shows how the steam-powered ,," horse led to the age of steam in the ‘tgerrohant navy, the sudden eruption of cot-

0,,shiPments to Britain, and the creation d' Lancashire's cotton industry and the ihev,eloPment of coal, steel and engineering " tne economy of Britain. c. After the hungry Forties, Bryant's naPter, the Fighting Fifties — Parliamen- tary fights to limit the hours of work, trou- ble after trouble in Ireland, the Chartists. In the quiet of the British Museum, Marx was grinding out his turgid prose to no political effect, while Hawthorne was describing a working man at a Mersey resort opening oyster after oyster 'in interminable succes-. sion'. The pleasure gardens, Vauxhall giv- ing way to Chelsea, Chalk Farm, Hackney, Hoxton, the Eagle at Islington and the Red House in Battersea. Then the crowning glory of Prince Albert's Great Exhibition, its planning and triumph brilliantly described by Bryant. For many the standard of living was rising, and with it a pride in Britain im- possible to separate from a contempt for foreigners. It was this which led the draymen from Barclays' Brewery to chase General Haynau, flogger or assumed flog- ger of rebel Hungarian ladies, bombarding him with mud pies, while seeking to cut off his beard.

Politics, as Bryant points out, reflected the mood of the people: Palmerston, after his Don Pacifico campaign, making in the House of Commons his Civis Romanus speech and getting away with it. Mean- while, Britain's pride in herself was receiv- ing ample proof by contrast with the French revolution of 1848 and the assumption of Imperial rule by Napoleon Ill in 1851. The Czarist Russians, floundering in the glories of the past, ran foul of Britain when they sought to challenge Britain's hegemony in the seas of Europe by pushing eastwards to seize the Ottoman Porte.

The Crimean War, despite the efforts of the Poet Laureate, was not one of Britain's greatest military successes, and soon our soldiers were beleaguered. And when His Holiness the Pope sought to give orders to the British clergy, Lord John Russell reacted from Downing Street, anticipating Palmerston in the vigour of his response. More of a spectacle, but a great struggle, was that contest between the two prize- fighters Sayers and Heenan, English and American, which continued two hours after the Englishman's arm had been broken, and was called off as a draw.

Generations of British schoolchildren have studied, for some to the point of ultimate boredom, the political struggles between Gladstone and Disraeli. Bryant's account is not a substitute for the text- books and the lengthy biographies, in- cluding his own writings, but it is a valuable adjunct to them. Civic emancipation, Irish Church disestablishment, Parliamentary reform are all covered, but more than that Bryant succeeds in making them appear as live people — different from the widely cir- culated full-length portrait, of which a full- size copy for years hung on my bedroom wall. And his admiration for Disraeli is not confined to overseas triumphs, or the crea- tion of a new Conservative party: he deals with the housing reforms and euphemisms that concern for the condition of the people associated with `Sanitas, sanitas, omnia est sanitas'.

Even the Irish problem is described in a humane and understanding way. For here, as throughout his book, Bryant (however strong his personal political views) does not classify men as 'goodies and baddies'. They are people, and he accords them fair treat- ment.

One feels that Sir Arthur drew less pleasure and excitement from his last few chapters, the sombre history of World War I, and the years of decline and slump which characterised the short period of peace before Hitler. He is friendly and sym- pathetic to Baldwin, and, as I have made clear in my book and broadcasts on Bri- tain's Prime Ministers, I believe the historians have failed to do Baldwin justice. He has been condemned because he was a man of peace in a war-torn world. He was too old in the crucial years of Hitler's rise to power — and it was Churchill who had ex- cluded himself from consideration by his unfortunate preoccupation with India.

I began by referring to Bryant's purpose, as I believe it to have been, in writing this book. It was a war book. It was not even a book about the actions which led to war following Hitler's rise to power. It is a book above all about the British people, written about them during the most dangerous crisis Britain has ever faced. And in fact it was the courage, resource and bravery of the British people — exactly as he had por- trayed by drawing on that people's history — which, he clearly never doubted, would lead to victory.

Previous page

Previous page