A house with a view

Tim Parks

A TUSCAN CHILDHOOD by Kinta Beevor Viking, .04.99, pp. 267 Here's a curious tale. Penniless painter Aubrey Waterfield marries rich Lina Duff Gordon Young in 1903. And as well as each other they fall in love with a 15th- century castle overlooking Au11a, a small Tuscan town in the river valley that leads up from La Spezia to the Passo della Cisa. Impulsively and, one feels, injudiciously, they buy the huge place and embark on an extravagant restoration programme includ- ing an idyllic roof-garden. He covers the walls with frescoes of romantic scenery in a style one suspects was already long out of date. She types up books on Italy, articles for the Observer. The children, when they come, are largely ignored, abandoned to the whim of peasant servants, left to their own devices in a magnificent but dangerous landscape. Kinta Beevor was the third and last of those children and A Tuscan Child- hood is her story of those days.

Much of the interest is to be found between the lines. For the most part restricted to, or blessed with, the company of cook, housemaid and gardener, the narrator paints generous portraits of solid Tuscan folk and with quite astounding recall sets down meticulous and mouth- watering accounts of the menus these people put together 60 and even 70 years before, how they grew and gathered the food, how prepared it, how presented it, how it was received. For those fascinated by Italian cuisine this will no doubt be a must. But the less specialised reader is constantly wondering quite what these well-to-do English people are doing here. They seem committed to Italy, in the sense that they have made their home there and don't intend to go back. But they have no plans to educate their children in Italy, nor does their income ever appear to depend on the country. It is a place to admire, to study, a place for excursions, but a curious air of unreality hangs over life, a feeling that, for all their mutual respect and affec- tion, the Italians and British are perhaps on quite incompatible wavelengths.

This is not meant as a criticism. On the contrary, it is a source of much pleasant speculation. When the narrator describes summer holidays when the family camped for weeks in military tents high up in the remote Appenines, their food brought to them via mule train by the never-flagging servants, Aubrey under a tree painting his dramatic canvases, Lina reading books while she stirs a pot, the children running wild, and their guest, the poet Robert Trevelyan, striding across the hillsides chanting verses and stripping off to plunge in every river or pool he passes., one cannot but marvel at the incongruity of it all. The fact that the author never comments upon this aspect only makes the whole thing all the more charming. When in her teens she makes friends with Italians of her own class she discovers that she has what they call an anglo-becero accent, a mixture of English and the local dialect learnt from the servants. But then these wealthy Italians themselves speak English with' a cockney accent picked up from nannies imported from London. How strange, one can't help feeling, to have picked up a language and culture mainly through those who are in one's pay and trying to please. It can lead to a distorted perspective. On one page we learn that Aunt Janet's servants respected her so much they would never cheat on her. On the next we discover that her steward had in fact been stealing the farm's vermouth for years and selling it himself in Florence.

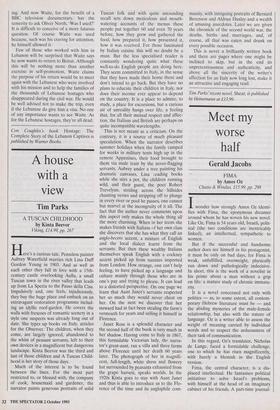

Janet Ross is a splendid character and the second half of the book is very much in her shadow. Having come to Italy in 1867, this formidable Victorian lady, the narra- tor's great-aunt, ran a villa and three farms above Florence until her death 60 years later. The photograph of her in magnifi- cent, full-length, white dress and flowery hat surrounded by peasants exhausted from the grape harvest, speaks worlds. In the 1920s Kinta goes to stay with Aunt Janet and thus is able to introduce us to the Flo- rence of the time and its anglophile com-

munity, with intriguing portraits of Bernard Berenson and Aldous Huxley and a wealth of amusing anecdotes. Later we are given the chronicle of the second world war, the deaths, births and marriages, and, of course, all that was eaten and drunk on every possible occasion.

This is never a brilliantly written book and there are pages where one might be inclined to skip, but in the end its unpretentiousness and authenticity, and above all the sincerity of the writer's affection for an Italy now long lost, make it an attractive and engaging read.

Tim Parks' recent novel, Shear, is published by Heinemann at 173.99.

Previous page

Previous page