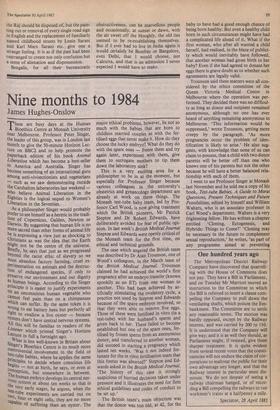

Goodbye to Calcutta

Alan Ross

The temperature is 105 degrees, humidity 100 per cent. Between now and the monsoon in two months' time both will get worse. Power cuts remain lengthy and unpredictable; the Japanese-built telephone system rarely works, and that vast trench running like a banked sewer through the centre of the city and allegedly to become a metro has not only made travel virtually impossible, but Calcutta hideous. As a child in the 1930s I thought Calcutta, that 'village of palaces', a heaven on earth, and on each of four visits during the last 20 years there appeared to be mitigating circumstances for evidence of `It's the unhappy hour, sir — all drinks are ten pence extra.' decline: the Bangladesh war, refugees, a Marxist government. The metro, unlikely ever to be finished, a permanent disfigure- ment, seems the last straw. It was the Russians a decade ago who foisted this folly, a central government not a state project, on Mrs Gandhi, then at her most susceptible. The advice of British, American, Japanese and various European traffic experts to go for roads or flyovers, easily constructed at a fraction of the cost, was rejected. No one in Calcutta that I spoke to held out much hope for its suc- cessful completion or operation. Most believe that it would even now — despite the large waste of money and effort — be safer and more sensible simply to fill it in. Instead, because of political pride and bureaucratic intransigency, spasmodic dig- ging will probably continue year after year, until Calcutta grinds finally to a halt. No work can be done in the rains, and only a quarter of every rupee spent contributes to the construction. The idea of trains actuallY operating under ground in Calcutta — PreY to subsidence, flooding, loss of power, ex- tremes of heat, to say nothing of an 11 evitable invasion of pavement-dwellers — is even more appalling than the desecration of the city and the waste. Meanwhile trams, buses, rickshaws, cows, cyclists, taxis, and old beat-up Am- bassador cars jostle along what little re- mains of the streets. The public and private buses, carrying double their proper load. s, frequently lose or squash their protruding passengers or overturn. In the suburbs or upcountry, pedestrians, who rarely look II; either direction when crossing the road, are regularly knocked down, though in surpris-

ingly few numbers, and when this occurs the offending bus, taxi or car is immediately surrounded and set on fire. The driver runs for his life and the passengers, too, if they are lucky.

Of course, Calcutta, that Brechtian city of the imagination — a metropolis beyond invention — has been, in the eyes of most people, in decline for over a century. Five generations of my family have lived there off and on, probably contributing to that, and a number of them have died there. The British cemeteries, in fact, are one of the few things that flourish. Though no longer a growth industry in the same way, their ghosts bloom under revived conservationist interest, pampered as few living things are in Calcutta.

One of my earliest memories of Calcutta is the race-course, the most centrally situated of any major city in the world. That, at least, has not changed. A couple of minutes from the colliery-like inferno of Chowringhee and lying between the Vic- toria Memorial and the Hooghly, its track, paddocks and turreted stands form the same fine flourish to the southern end of the maidan. There may no longer be palatial residences at Garden Reach, the handsome colonial houses of Alipore are mostly company flats or taken over by Mar- waris — those shrewd Rajastani entre- preneurs who have become the affluent scapegoats for all Bengal's economic in- justices — and Kidderpore docks are only a shadow of their former glory, but the race-

course, with its flags flying, its crisply- suited men and dazzling women, is as splen- did as ever. From the boxes on the members' stand, with Chowringhee only discernible at roof level, it might still be as I used to dream of it through a decade of adolescent separation. Satyajit Ray, to whom I delivered a viewing-filter and who lives in the next street — huge shabby houses among palms and banana trees where I used to visit my grandmother, says he could not imagine living anywhere else, so the dream must still be real for someone.

One thing the Bengal government learned from the Bangladesh war was that Calcutta can afford no more refugees. Accordingly, during the Assam atrocities, camps were set up in the frontier areas, and approaches to Calcutta sealed. Although criticism of Mrs Gandhi for persisting with the elections in Assam remains fairly general, tea-planters who have spent their whole lives there do not support it. According to them, there was little reason to predict butchery, cer- tainly not on the scale that took place. Plainly, government advisers underesti- mated the real or contrived ferocity of local feeling, but if it was a misjudgment there was no precedent for acting otherwise.

In general it is impossible not to be amaz- ed at the good humour and gentleness with which Indians, and the people of Calcutta especially, support the trials of their ex- istence. Yet the violence when it erupts is horrifying. Large-scale demonstrations are no problem. Thousands mass on the maidan under local banners, the harangu- ing goes on all day, and then, when everyone is worn out, they disperse peacefully and return to their homes. It is the individual violence that shocks. Hardly a day passes without reports of an un- wanted wife or daughter-in-law being set fire to and burned to death; last week, in a change of roles, a wife set fire to her hus- band.

rr here is no green quite like the green of Bengal. And once you are out of Calcutta the landscape assumes the timeless quality and serene beauty that haunt for ever those who fall prey to it: the raised, ruler-straight road lined with tamarind, peepul, bamboo, mango, gol mohur, ashoka; wheat and rice stretching away to the horizon; water buffaloes, only heads visible, motionless in hyacinth-filled lakes; the occasional cyclist under a black um- brella and, at the hour of the cowdust, creaking bullock carts. The villages are mere scatters of thatched huts and markets, rivers curve under coconut palms, women in turquoise, lemon or pink saris stride in their marvellous way under pitchers or cop- per bowls. Within half an hour Calcutta simply seems an aberration. The empty bat- tlefield of Plassey, recorded by a single monument, or the Residency ruins at Lucknow have more immediacy than the broken sewage-pipe washing facilities and lightless suburbs of Calcutta.

No matter whom you ask, `corruption' is always the answer when you try to assess responsibility for inefficency and chaos; corruption among politicians, civil ser- vants, petty officials, businessmen. Nothing proceeds without bribery, to such an extent that the inhabitants of Calcutta are disinclined to believe that this is not stan- dard practice everywhere for everything. At the same time West Bengal, under its Marx- ist government, has one of the most honest and civilised administrations in India. Un- fortunately, it is also a power-conscious one and investment in Bengal has as a conse- quence dried up. J. R. D. Tata, the 70-year- old head of the Tata empire and one of the shrewdest men in India, recently gave an in- terview to Calcutta's new newspaper the Telegraph (better written and printed than any of its older rivals) in which he laid much of the blame for India's present plight on Nehru's adherence to the Soviet pattern of industrial development and neglect of agriculture. According to Tata, the dismantling of bureaucracy, as recently achieved by Jayewardene in Sri Lanka, and a change from a parliamentary to an Indian-adapted presidential system offer the only hope of reversing the present slide into disorder and bankruptcy. Affection for a city can blind one to almost anything. I don't think, all the same, that I shall ever want to return to Calcutta; not only because of its un- sightliness and the relentless degradation of human life there, but because, for the first t

time, I felt it as a faintly hostile place. was to be expected that all monuments t0

the Raj should be disposed of, but the pain- ting out or removal of every single road sign in English and the replacement of familiarly named childhood streets by Lenin Sarani and Karl Marx Sarani etc. , give one a strange feeling. It is as if the past had been rearranged to create not only confusion but a sense of alienation and dispossession.

Bengalis, for all their bureaucratic obstructiveness, can be marvellous people and occasionally, at sunset or dawn, with the air sweet off the Hooghly, the old ties seemed to be re-establishing themselves. But if I ever had to live in India again it would certainly be Bombay or Bangalore, even Delhi, that I would choose, not Calcutta, and that is an admission I never expected I would have to make.

Previous page

Previous page