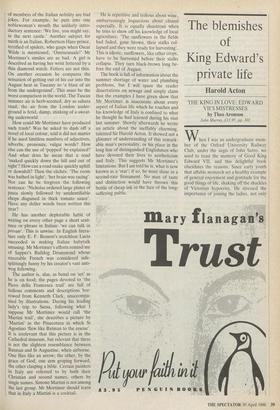

The blemishes of King Edward's private life

Harold Acton

THE KING IN LOVE: EDWARD VII'S MISTRESSES by Theo Aronson

John Murray, £13.95, pp. 301

When I was an undergraduate mem- ber of the Oxford University Railway Club, under the aegis of John Sutro, we used to toast the memory of Good King Edward VII, and this delightful book elucidates the reasons. Since early youth that affable monarch set a healthy example of general enjoyment and gratitude for the good things of life, shaking off the shackles of Victorian hypocrisy. He stressed the importance of joining the ladies, not only

after dinner. Each of the exceptional trio who basked in his favours was a beauty by contemporary, even by classical, stan- dards, and each has far more to offer than mere pulchritude, but one doubts if they would be appreciated by the fans of Holly- wood stars, for tastes have changed con- siderably since King Edward's reign.

Apart from their physical attributes, Lil- lie Langtry, Lady Warwick and Mrs George Keppel were highly intelligent if not intellectual, and Mrs Keppel, whom I knew when she retired to Florence with exquisite dignity, endeared herself to all who had the pleasure of meeting her as a grande dame of spontaneous wit and uni- versal sympathy. Wherever she went she retained a semi-regal aura. Mrs Langtry, who became Lady de Bathe, was still a cynosure at Monte Carlo in her fifties. But the handsome Lady Warwick introduced a note of melodrama into the story when she tried to resort to blackmail. Apart from the latter, who paraded as an ardent socialist in later life, these royal mistresses behaved with commendable tact and discretion. Above them towered the gracious figure of Queen Alexandra, who understood and tolerated her husband's all-too-human weaknesses.

Now that the private lives of royalty are open to every kind of publicity, Mr Aron- son has regaled us with a detailed account of King Edward's extra-marital adven- tures. This is a breezy sequel to Philip Magnus's restrained biography, which was also published by John Murray. It is crammed with amusing anecdotes, some of which should be taken with a grain of salt. For instance one cannot visualise Oscar Wilde introducing Lillie Langtry to John Ruskin or teaching her Italian. From his plethoric and platitudinous sources, with the notable exception of Wilfrid Scawen Blunt's secret diary, Mr Aronson has extracted the very essence of the period, and his application of such words as 'adulterous' and 'betrayed' reminds one poignantly of the needle-in-the-haystack research he waded through in order to write it. On the subject of contraceptives, en passant, he is encyclopaedic.

Giving the whole question of the use of condoms an aura of reassuring respectability was the box in which they were sold . . . The manufacturers had no hesitation in illustrat- ing their new product with portraits of the two most irreproachable Victorian notables they could think of . . . Queen Victoria and Mr Gladstone.

While enjoying this racy account of what moralists would term the blemishes of King Edward's private life, we should not lose sight of his public achievement, so memor- able in Philip Magnus's biography, 'the zest, punctuality and panache with which he performed his duty forcefully and faith- fully until the day in which he died.' In public as in private relations King Edward was supreme.

Previous page

Previous page