Look and pass on

Andro Linklater

CITY LIGHTS: A STREET LIFE by Keith Waterhouse Hodder, £14.99, pp. 218 Joumalists may be good at writing about the world around them — it is, after all, their trade — but they are rotten at describing the world inside them. Were it otherwise, they would be novelists.

Although Keith Waterhouse is the author of a style-setting novel, Billy Liar, and a vastly successful play, Jeffrey Bernard is Unwell, he is pre-eminent as a journalist, and it is in that guise that he has written this beguiling account of his early life. As a result, you will learn from it much that is entertaining about the sights and sounds and smells of Leeds, where he grew up in the 1930s and 1940s, but nothing of the development of the Waterhouse psyche.

This is a pity, for as a solitary child, the youngest of five brought up almost single- handed by their mother following the death of their father, a costermonger, he evident- ly lived largely within his own wonderfully speculative imagination. To feed it, he quickly developed the habit of bunking off school, preferring to make long journeys into the centre of town, where he would wander through streets and public buildings and stare wonderingly into shop- windows — at the pies displayed in Redman's, 'and previous to that at the Horse Meat Shop and the Murder Shop and then Montague Burton the Tailor of Taste'. As he stared he would ponder the nature of reality — the physics of fitting a boiled egg into a veal, ham and egg pie, the equine anatomy which lumps of purple and yellow meat in the Horse Meat Shop once formed, and the frailty of life suggested by a display of knives and scissors in what he thought of as the Murder Shop.

'I suppose I was a weird child all round', he comments, as though momentarily pre- pared to explore further the wealth of fantasy that drove him to construct elaborate toy theatres and hand-written newspapers for his bemused mother. But the use of this rich material is apparently restricted to his novel of childhood, There is a Happy Land. Here his gaze remains outwards, and he conveys his developing personality through the single device of slowly widening the focus of his observa- tion. From the contents of shop-windows, it lifts to the architecture of the shop itself, and from speculations about the murder- ous properties of a knife to his first murder trial as court reporter.

In a reversal of the normal pattern, he refers to his writing as an attempt to escape from fantasy into realism. 'All along, I was rehearsing for what I was determined would be the shape of my adulthood', he insists, and the evidence bears him out. From his first accepted article in the National Savings News at the age of 12, by way of freelance contributions while still an undertaker's office-boy and RAF clerk, his ambition remains constant. By the time he reaches the final eminence of by-lines in the Yorkshire Evening Post with a future in Fleet Street and foreign assignments firmly in view, it is impossible not to share his sense of triumph.

He quotes as 'the best possible advice for an aspiring journalist', J. M. Barrie's sensi- ble, sententious admonition:

Do not fruitlessly aspire towards internation- al travel and the drawing-rooms of the mighty in your search for a topic, but write about the small, everyday events of your own existence, and these accounts will sell.

Coming from one of Fleet Street's highest paid columnists, this is a useful recommen- dation, but to write interestingly of every- day events, it also helps to subject them to the same intense scrutiny that he gave to pies and cutlery, and later to architecture and towns. Next to the driving ambition, it is this capacity for observation that is most evident in his determined ascent of the journalistic ladder.

The lack of psychological underpinning sometimes allows his tone to sag danger- ously close to Wallace Arnold banality —

With my Yorkshire Evening Post propped up against an electro-plated teapot, and a fish- cake (3d) on my plate, I whiled away many a happy hour in Joe Lyons —

but this was never meant to be a weighty structure. The style is deliberately light and amusing, and his journey is set against a cinematic background of England's manu- facturing towns in the 1940s, as in this glimpse of Birmingham —

a seething provincial metropolis of trams, blackened municipal buildings in the Italian Renaissance style, steam-enshrouded railway stations, markets, statues of Queen Victoria, commercial hotels, and arcades with striking clocks.

I can recommend it as ideal bathtime reading — with one serious reservation. In a fit of penny-pinching, his publishers have chosen a cheap, coarse grade of paper, and at the first tendril of steam it begins to recycle itself into pulp. Not even a journal- ist deserves such evanescence.

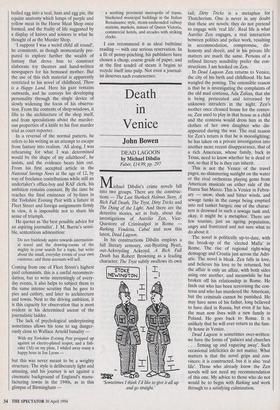

Previous page

Previous page