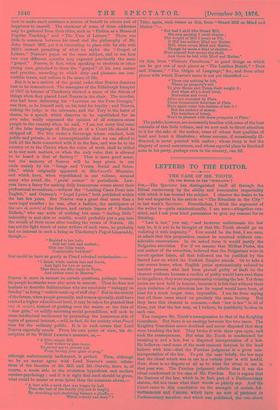

THE LATE LORD NEAVES.

ANOTHER light in the Scotch Israel of wit allied to wisdom —how sadly has the dying year reduced it in numbers !— has gone out, and its extinction is all the more to be regretted, that it was a light of other days. Charles Neaves, the oldest Senator in the Scotch College of Justice, popularly known as Lord Neaves, died last week, at the ripe age of seventy-six, and with him passes away an old literary and legal tradition. Scot- land has still left to it Professor Blackie, to make somewhat noisy and rollicking, but sincere outbursts against social conven- tionalities, and the still, sweet voice of Dr. John Brown; but they belong, in spirit, if not in years, to a younger generation. Neaves was the last, if not the best, of a set of jovial Edinburgh

pessimists, who wore wigs till five o'clock in the afternoon, then threw them aside for "soft nights and splendid dinners," at which they cracked innumerable jokes, improvised innumerable verses, passed innumerable bottles, quoted Horace and Anacreon, cursed the Whigs, embraced each other, and at an early hoar in the morning declared the country had gone to the dogs. Neaves was present at the dinner at which Scott lifted up the mask of the "Great Unknown ; " he " assisted " at the dinner at which, under the presidency of Wilson, Edinburgh did honour to Dickens; he was chairman at the dinner at which Edinburgh did honour to Thackeray ; he was, in fact, the best public and private diner-out of his city and country ; his oratory and the songs of his own composing and singing were the delight of every company he entered ; and when in these later years old age forbade him the luxury of late hours, and the an- nouncement of "Lord Neaves's carriage" interrupted that flow of soul which to intelligent auditors was in its own way a feast of reason, a loss was felt in the crowded drawing-room which no symphony or fantasia, however brilliantly executed, could supply. Comparing the Toryism of the old school, and its days of adversity with that of the new school which has risen to power and place under Lord Beaconsfield, one cannot help sighing,—Tempora muiantur. We read the other day an account of a dinner given in honour of the return of the Scotch Lord-Advo- cate for the Universities of Glasgow and Aberdeen. On such an occasion as the celebration of a victory, it might have been expected that the proceedings would have been enlivened by merriment, if not spiced with wit. Instead of this, they were as solemn as a funeral, and were not even graced with funereal eloquence ; the speeches made by a few middle-aged lawyers with stout lungs, who, at the top of their voices, pooh-poohed the Bulgarian atrocities, and declared their adhesion to a policy of sewage, were simply what Lord Westbury once designated the de- cisions of a Scotch Lord of Session, "melancholy collections of erroneous sentences " ; while Dr. Andrew Wood, who has endeavoured to translate Horace, and perhaps on that account occupied the post of humourist of the evening, was actually mala- droit enough to sing the praises of the most un-English of Pre- miers under theguise of the Fine old English Gentleman." Shades of Scott, of Lockhart, and of Wilson, is to it to this that the Toryism of the Quarterly and of Blackwood is reduced ! Have the little fishes taken the place of the great gods ? Is dull success an adequate substitute for merry misfortune, this Wooden eulogium for that brilliant vituperation ?

Lord Neaves was, however, something more than in his earlier days an admirable example of the Tory of "the good old school," and in his later a diner-out who made dining a pleasure and a profit alike to himself and to others. We have the authority of those who knew him beat that he was an able and a trusted ad- vocate and judge. His humour was such as to enable him in the one capacity to puncture a sophism, and in the other to temper the instruction of a counsel, and even the reproof of a prisoner, with kindliness. But to the outside world, that never met Neaves in Court, at a " circuit " dinner, or in an Edinburgh salon, he was something more than all this. His literary remains are small in bulk, but they are so admirable in quality that one can hardly help wishing that his contemporaries had not found him so "producible" in society, for in that case he might have been more productive for the benefit of posterity. He was a man of substantial culture of the old classical sort, which he showed in various ways, in his pleasant little volume, "The Greek Anthology," which has a place in the pleasant little series of "Ancient Classics for English Readers ;" in forgotten papers, read before the Edinburgh Royal Society ; and above all, in a series of Blackwood articles on Grimm, which have been much and de- servedly praised even by German philologists, and which indicate that his early studies had budded in mature life into an accurate knowledge of the science of language. These painstaking acquisitions, it may be thought, had no particu. lar value in connection with the profession he adopted and the position he occupied, but it is probable they were not unrelated to that knowledge of legal precedents, that erudition in "cases," in which he is generally believed to have had no rival among his brothers of the Scotch Bench. His con- tributions to miscellaneous prose literature consist almost entirely of addresses to various societies and to the students of the Uni- versity of St. Andrew, who elected him as their Rector ; and they are chiefly notable as the pleasant expression of the sincere opinions of one who knew men as well as books, and looked upon pleasure, and even laughter as valuable factors, to be reckoned when attempting to solve the problem of how to live rationally,

how to make one's existence a source of benefit to others and of happiness to oneself. The character of some of these addresses may be gathered from their titles, such as "Fiction as a Means of Popular Teaching," and "The Uses of Leisure." There was little in common between his creed and the philosophy of Mr.

John Stuart Mill, yet it is interesting to place side by side with Mill's earnest preaching of what be styles the "Gospel of Leisure," Neaves's paper on the same subject, and to see how two very different apostles may expound practically the same "gospel." Neaves, in fact, when speaking to students or other young men, preached to them the "gospel" of his own nature and practice, according to which duty and pleasure are con- vertible terms, and culture is the sauce of life.

But it is as a satirist of the genial order that Neaves deserves best to be remembered. The managers of the Edinburgh banquet of 1857 in honour of Thackeray showed a sense of the fitness of things when they placed Lord Neaves in the chair. The novelist, who had been delivering his "Lectures on the Four Georges," was then, as he himself said, on his trial for loyalty ; and Neaves, sinking the judge in the advocate, and the Tory in the hater of shams, in a speech which deserves to be republished for its own sake, really expressed the opinion of all common-sense people in the country when he said, "I am not sorry that some of the false trappings of Royalty or of a Court life should be stripped off. We live under a Sovereign whose conduct, both public and private, is so unexceptionable that we can afford to look all the facts connected with it in the face, and woe be to the country or to the Crown when the voice of truth shall be stifled as to any such matters, or when the only voice that is allowed to be heard is that of flattery !" That is mere good sense, but the memory of Neaves will be kept green in our souls mainly by his "Songs and Verses, Social and Scien-

tific," which originally appeared in Blackwood's Magazine, and which have, when republished in one volume, amused

many who avoid the "poets' corner" in periodicals. Law- yers have a fancy for making drily humourous verses about their professional avocations,—witness the "Leading Cases Done into English," and Outram's "Legal Lyrics," both published within

the last few years. But Neaves was a great deal more than a mere legal versifier ; he was, after a fashion, the anticipator of the vers de socie'te of the future, and certain lispers of "Boudoir Ballads," who can write of nothing but some "darling little"

imbecility in seal-skin or muslin, would probably put a gag into the mouth of their muse after reading the verses of Neaves. He has not the light touch of some writers of such verse, he probably had no interest in such a being as Thackeray's Peg of Limavaddy, though,—

"Braided is her hair, Soft her look and modest ; Slim her little waist, Comfortably boddiced."

Nor could he have so gently as Praed rebuked sectarianism :— "I think, while zealots fast and frown, And fight for two or seven,

That there are fifty roads to Town, And rather more to Heaven."

Neaves is more in earnest on certain questions, perhaps because the people he attacks were also more in earnest. Thus he does not hesitate to describe Sabbatarians who are resolutely "unhappy on Sunday" as being "zealots made up of stiff clay." But in the society of the future, when people generally, and women specially, shall have reached a higher educational level, it may be taken for granted that vers de societe, instead of gushing over the waists or the furs of "dear girls," or mildly satirising social peccadilloes, will seek to cause intellectual excitement by presenting the humorous side of topics of general interest,—will, in fact, do for society what Punch

does for the ordinary public. It is in such verses that Lord Neaves especially excels. From his own point of view, his de- scription of Sir Wilfrid Lawson's measure, as,—

" A little simple Bill, That wishes to pass ineog., To permit me to prevent you

From having your glass of grog,"

although unfortunately hackneyed, is perfect. Then, although we by no means agree with Lord Neaves's comic refuta- tions of the theories of Mr. Mill and Mr. Darwin, there is, of course, a comic side to the evolution hypothesis and modern cerebro-psychology ; and if it is right that such should be given, what could be neater or even fairer than the nonsense about,—

" A deer with a neck that was longer by half Than the rest of the family (try not to laugh), By stretching and stretching became a giraffe,—

Which nobody can deny" ?

Take, again, such verses as this, from "Stuart Mill on Mind and Matter :"—

" But had I skill like Stuart Mill,

His own position I could shatter ; The weight of Mill I count as Nil, If Mill has neither Mind nor Matter.

Mill, when minus Mind and Matter, Though he made a kind of chatter,—

Must himself first mount the shelf, And there be laid with Mind and Matter."

Or this; from "Platonic Paradoxes," as good things as which can be got out of such pieces as "The Leather Bottel," "Dust and Disease," "The Origin of Language," &c., and from other pieces with which Neaves's name is not yet identified :—

a There can nothing be loft,

Where no property's left To give Meum and Tuum their weight 0; And when all's a dead level, Starvation and revel Alike are excluded by Plato.

These Communist doctrines of Plato Have again come into fashion of late 0!

But the makers of money, The hoarders of honey, Won't be pleased with these prospects of Plato."

The public, however, are necessarily familiar with some of the best contents of this little volume, and we now seek to direct attention to it for the sake of the author, some of whose best qualities of head and heart it illustrates ; whose sarcasm, if occasionally ill- directed, is never pointed with malice ; whose irony is but the drapery of moral earnestness, and whose especial place in Scotland none in his party, perhaps even in his country, can fill.

Previous page

Previous page