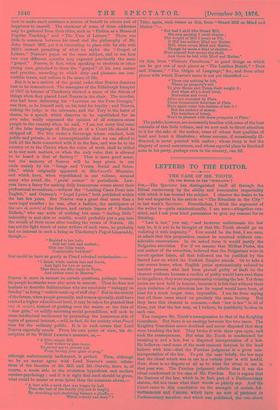

LETTERS TO THE EDITOR.

THE CASE OF MR. TOOTH.

[TO THE EDITOR OF THE "SPECTATOR.']

SIR,—The Spectator has distinguished itself all through the Ritual controversy by the ability and honourable impartiality with which it has treated the subject. I observe the desire to be fair and impartial in the article on "The Ritualists in the City" in last week's Spectator. Nevertheless, I think the argument of the writer is—quite unintentionally, I am sure—altogether one- sided, and I ask your kind permission to give my reasons for so thinking.

"Law is law," you say, "and however unfortunate the law may be, it is not to be thought of that Mr. Tooth should go on violating it with impunity." You would be the first, I am sure, to admit that this proposition cannot be received without con- siderable reservations. In its naked form it would justify the Bulgarian atrocities. For if we assume that Midhat Pasha, the real author of the atrocities, believed that the Bulgarians were in revolt against Islam, all that followed can be justified by the Sacred Law on which the Turkish Empire stands. Or to take a case nearer home, when English juries systematically refused to convict persons who had been proved guilty of theft on the clearest evidence because a verdict of guilty would have sent them to the gallows, they were unquestionably violating the law. Yet those juries are now held in honour, because it is felt that without their open violation of an atrocious law its repeal would have been, at least for a much longer time, impossible. I am far from saying that all these cases stand on precisely the same footing. But they have this element in common,—that "law is law" in all of them, yet that the law may, as I believe, be justifiably broken in each case.

You compare Mr. Tooth's transgression to that of the Keighley Guardians. But there is no analogy between the two cases. The Keighley Guardians never doubted and never disputed that they were breaking the law. They broke it with their eyes open, and took the consequences. But what Mr. Tooth is condemned for breaking is not a law, but a disputed interpretation of a law. He believes—and some of the most eminent lawyers in the land believe with him—that the Purchas judgment is a gross mis- interpretation of the law. To put the case briefly, the law says that the ritual which was in use in a certain year is still lawful. Now, there is no dispute at all as to what the ritual in use in that year was. The Purchas judgment admits that it was the ritual condemned in the case of Mr. Purchas. But it argues that the framers of the law, which is, in fact, part of a Parliamentary statute, did not mean what their words so plainly say. And the Court came to this conclusion on the strength of certain Ad- vertisements and Canons, which have no sort of pretence to Parliamentary sanction, and which was published, the one about

-a century, the other about half a century, before the Act of ?ornament which they are supposed to have repealed.

I have argued, and I think proved, elsewhere that those Canons -and Advertisements do not support the conclusion on behalf of which they have been cited, but, on the contrary, upset it. The important thing to observe, however, is that the appeal to the Advertisements and Canons at all is about as irrelevant a digres- sion as was ever perpetrated by a Court of justice anywhere. It is, I believe, a maxim of English law that "a verbis legis non eat recedendum," and in Edrick's case the Judges decided that "they ought not to make any construction against the express letter of the statute ; for nothing can so express the meaning of the makers of the Act as their own direct words, for index animi, sermo." Now the index animi of the Ornaments' rubric, judged by this testris clear and precise beyond dispute. Equally clear and indis- putable is it that the Purchas judgment is a glaring "construe- lion against the express letter of the statute."

Take a parallel case. Not long ago an English Court of Justice had to decide on the validity of crossed cheques. There was no doubt as to what the framers of the Act meant, for it was passed -quite recently. But the Judge—Lord Cairns, I think—held that the language of the Act did not convey the intention of the Parli- ment which passed it ; and like a good lawyer, he decided in favour of the language of the statute, and discarded the inten- tion of its framers. If it bad been a Ritual case, how would the judgment have gone? It is not difficult to guess, if the Parches judgment is to be our guide.

But Mr. Tooth has a second grievance in the Public Worship Regulation Act. That Act was passed, in the words of its most -authoritative supporter, "to put down Ritualism." Just see what that means. If Mr. Disraeli, in a fit of fictitious Protestantism, lad manfully proposed a short Act making " Ritualism " illegal, I could applaud his straightforwardness, whatever I might think of his Protestantism or wisdom. But the Public Worship Regula- tion Act is not ostensibly an Act to make Ritualism illegal, but to find out whether it is illegal or not. Yet the first Minister of the 'Crown declared, amidst the ringing cheers of the House of Com- mons, that the intention of the Act was not to create a Court which should try the legality of Ritualism, but which should " put it down ;" not a Court which should decide according to the -evidence, but which should find the accused guilty.

Is it surprising that an Act passed with this Parliamentary -imprimatur as to its intention should be met by its victims with passive resistance? They received fair and open warning that the Act was intended not to do them justice, but "to put" them 4i down," and the event seems to have justified the warning. Mr. Ridsdale pleaded before the Judge of the new Court, and was condemned. He appealed to the Court above, but contrary ta -the usual practice, the judgment of the Court below is put in force pending the appeal.

This was bad enough, but worse followed. If the adminis- trators of the law had any sense of justice, they would surely have allowed no prosecutions of Ritualists until the Ridsdale -appeal had been heard. No case under the Act can be put in motion without the consent of the Bishop of the diocese. Some of the Bishops have refused their consent ; others, including the Bishop -of Rochester, Mr. Tooth's diocesan, have allowed prosecutions to -go on. I never saw Mr. Tooth, I never saw his church, but [am told that it is a case where incumbent, parishioners, churchwardens, and the patron of the living are all united, the threenggrieved parishioners being men of straw, put up by the Church Associa- tion. I believe there is hardly any endowment, and I am told that Mr. Tooth spends a great deal more on the parish than he 'receives from it. Let us suppose, then, that your advice is fol- lowed, that the church is closed on Mr. Tooth, and the living sequestrated. Mr. Tooth, with his congregation and church- wardens, will retire to another building, which the law cannot touch. The Bishop may withdraw his license, but the service -will continue, and Mr. Tooth meanwhile will be invited to officiate by clergy who agree with him in other dioceses. At the end of three years the living lapses under the Act, and the patron pre- sents a man like-minded with Mr. Tooth, who will restore the condemned ritual and receive back the old congregation.

This is a sketch of what may happen, and probably will happen, in many parishes, under the operation of the PubliC Worship Regulation Act. As far as I can understand—and I have taken some pains to learn—the Ritualists have pretty well made up their minds that no justice or fair-play is to be expected from a judicial tribunal which was created ostentatiously for the express purpose of " putting " them "down," and which has so far been 'administered with open partiality against them. They have accordingly determined to disregard it, and take the con: sequences ; and the English Church Union, consisting chiefly of laymen, including Members of both Houses of Parliament, will probably support this resolution.

This is the result which the Spectator predicted from the first, as likely to issue from the Public Worship Regulation Act. Those who presided over the incubation and parturition of that Act will probably appreciate the mischief of their painful labours when it is too late to repair it. I believe that the Ritual move- ment might have been easily controlled, if treated with decent fairness, and with even a glimmering of statesmanship. But the Ritualists, after all, are Englishmen ; the vast majority of them belong to the laity, and to put them down by the perverted construction of a plain statute may turn out to be a task which is much easier said than done. I believe they would much prefer to see an Act of suppression passed openly and honestly against them, to the violent twisting of the law to their prejudice. It is a bad thing to make the law so thoroughly an instrument of party oppression, that any class of her Majesty's subjects should lose all confidence in its righteous administration.

Previous page

Previous page