WHERE THE CRUSADES LIVE ON

Nine hundred years later, Anton La Guardia

finds an issue on which Arabs and Israelis unite

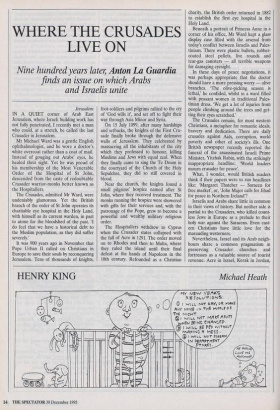

Jerusalem IN A QUIET corner of Arab East Jerusalem, where Israeli building work has not fully penetrated, I recently met a man who could, at a stretch, be called the last Crusader in Jerusalem.

Mr Michael Ward was a gentle English ophthalmologist, and he wore a doctor's white overcoat rather than a coat of mail. Instead of gouging out Arabs' eyes, he healed their sight. Yet he was proud of his membership of the Most Venerable Order of the Hospital of St John, descended from the caste of redoubtable Crusader warrior-monks better known as the Hospitallers.

The Crusades, admitted Mr Ward, were undeniably glamorous. Yet the British branch of the order of St John operates its charitable eye hospital in the Holy Land, with himself as its current warden, in part to atone for the bloodshed of the past. 'I do feel that we have a historical debt to the Muslim population, as they did suffer severely.'

It was 900 years ago in November that Pope Urban II called on Christians in Europe to save their souls by reconquering Jerusalem. Tens of thousands of knights, foot-soldiers and pilgrims rallied to the cry of 'God wills it', and set off to fight their way through Asia Minor and Syria.

On 15 July 1099, after many hardships and setbacks, the knights of the First Cru- sade finally broke through the defensive walls of Jerusalem. They celebrated by massacring all the inhabitants of the city which they professed to honour, killing Muslims and Jews with equal zeal. When they finally came to sing the Te Deum in the courtyard of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, they did so still covered in blood.

Near the church, the knights found a small pilgrims' hospice named after St John, where they received treatment. The monks running the hospice were showered with gifts for their services and, with the patronage of the Pope, grew to become a powerful and wealthy military religious order.

The Hospitallers withdrew to Cyprus when the Crusader states collapsed with the fall of Acre in 1291. The order moved on to Rhodes and then to Malta, where they ruled the island until their final defeat at the hands of Napoleon in the 18th century. Refounded as a Christian charity, the British order returned in 1882 to establish the first eye hospital in the Holy Land.

Beneath a portrait of Princess Anne in a corner of his office, Mr Ward kept a glass display case filled with the arsenal from today's conflict between Israelis and Pales- tinians. There were plastic bullets, rubber- coated steel pellets, live rounds and tear-gas canisters — all terrible weapons for damaging eyesight.

In these days of peace negotiations, it was perhaps appropriate . that the doctor should have a more pressing worry — olive branches. 'The olive-picking season is lethal,' he confided, whilst in a ward filled with peasant women in traditional Pales- tinian dress. 'We get a lot of injuries from people climbing around the trees and get- ting their eyes scratched.'

The Crusades remain, for most western Christians, a metaphor for romantic ideals, bravery and dedication. There are daily crusades against Aids, corruption, world poverty and other of society's ills. One British newspaper recently reported the funeral of the assassinated Israeli Prime Minister, Yitzhak Rabin, with the strikingly inappropriate headline: 'World leaders mourn crusader for peace'.

What, I wonder, would British readers think if their papers were to run headlines like: 'Margaret Thatcher — Saracen for free market', or, 'John Major calls for Jihad for peace in Northern Ireland'?

Israelis and Arabs share little in common in their views of history. But neither side is partial to the Crusaders, who killed count- less Jews in Europe as a prelude to their holy war against the Saracens. Even east- ern Christians have little love for the marauding westerners.

Nevertheless, Israel and its Arab neigh- bours share a common pragmatism in preserving Crusader churches and fortresses as a valuable source of tourist revenue. Acre in Israel, Kerak in Jordan, Crac des Chevaliers in Syria, these are all visited by hordes of westerners seeking to rediscover the stories of Richard Lion- heart and Saladin, who reconquered Jerusalem for the Muslims. When peace breaks out in the Middle East, rest assured that Crusader tours of the region will soon be on offer.

Sir Steven Runciman, the British scholar of the Crusades, concludes his classic his- tory of the period with the glum assess- ment that the Christian enterprise was a `vast fiasco', marked by ignorance, greed and jealousy. The real surprise was not that the Crusader states were vanquished, but that they lasted for two centuries.

There was so much courage and so little honour, so much devotion and so little understanding [he wrote]. . . . High ideals were besmirched by cruelty and greed ... the Holy War itself was nothing more than a long act of intolerance in the name of God, which is the Sin against the Holy Ghost.

The Crusaders left a legacy of enmity between Islam and western Christianity, between the Arab world and the West. Christian intolerance begat Muslim intol- erance. The Arab world defeated the Cru- saders, but feels dominated by their western descendants. Muslim radicals now call for the Islamic mirror-image of a Cru- sade —Jihad, or holy war, against the West.

The Arab historian Amin Maalouf wrote in his account of the Crusades:

It seems clear that the Arab East still sees the West as a natural enemy. Against that enemy, any hostile action — be it political, military or based on oil — is considered no more than legitimate vengeance.

A lesser known impact of the Crusades was the widening schism between the east- ern and western Churches. In 1095, Pope Urban had called on Christians in Europe to save their co-religionists in the East. But in the end the Crusades fatally weakened the Byzantine Empire. The western knights sacked Constantinople in 1204, and by the 15th century Byzantium had fallen under Muslim rule.

The Greek Orthodox Church never for- gave the West. In Jerusalem, the tombs of the first Crusader kings were mysteriously removed from the Church of the Holy Sepulchre when the Greeks restored the building after a fire in 1808. Two wooden benches now mark the places where Bald- win I and Godfrey of Bouillon once lay.

The Arabs refer to the Crusaders as the Tranf (the Franks), and the word has become a synonym for all perceived west- ern enemies of Islam: the French, accord- ing to Algerian militants, and the United States, according to radicals in Gulf coun- tries.

And, for almost everybody in the Arab world, Israel is the new Crusader kingdom that will, with time, be removed from Mus- lim lands. The parallel is made easily: a small, determined group of foreigners establish a state by force of arms, because the Arabs cannot unite to confront the threat. So, Arabs ask, when will there be a new Saladin who will sweep away the region's petty rulers and unite the Arabs to reconquer Jerusalem?

More than one leader would like to claim the mantle. President Hafez al- Assad of Syria is lovingly restoring Sal- adin's tomb in Damascus. Meanwhile Saddam Hussein's fawning underlings have produced booklets showing the Iraqi President and Saladin, who were both born in the town of Tikrit, shaking hands.?

Arab rhetoric about the West's continu- ing Crusade serves to obscure more than to inspire. It is a symptom of the Arab's failure to create stable institutions, or leaders who rule by consent rather than coercion. For most Arabs, personal free- dom is a luxury, and even a decent stan- dard of living seems unattainable. The longing for Saladin shows that change comes only from leaders, not from the people.

After a day spent visiting the mighty but desolate Crusader fortress of Crac des Chevaliers, north of Damascus, I spoke to Mr Suheil Zakkar, a historian at the Uni- versity of Damascus. 'Will there be a sec- ond Saladin? I don't think so,' he said.

I asked him why the Crusades still arouse such hatred, while the destructive Mongol invasions have been forgotten by Arabs. 'Where are the Mongols today? They don't exist,' he replied. 'But the West is still around.'

Anton La Guardia is the Middle East corre- spondent of the Daily Telegraph.

Previous page

Previous page