The jaundiced genius

Raymond Carr

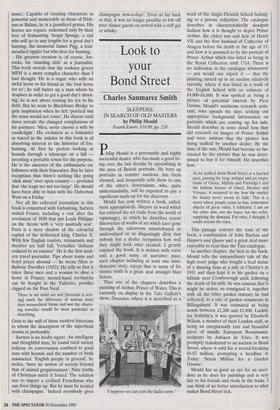

MR JORROCKS' THOUGHTS ON HUNTING AND OTHER MATTERS by Robert Smith Surtees The RS. Surtees Society, Rivrside House, Nunney, Nr, Frame, Somerset, BAll 4 NH, £18.60, pp. 289 Men write to keep at bay the black dog of melancholy and boredom; to make some cash on the side; for a parcel of fame; and, in the case of Surtees, to work off their enthusiasms and prejudices, some- times to pay off old scores.

Fame was not the spur of R. S. Surtees, a reserved, puritanical Durham squire; his ferocious protection of his anonymity rules that out. A second son, sent south by his father to study for the law, he was bored, hard up, and lonely in London. He took to journalism, writing sketches for the sport- ing press. A sample of his articles of the 1830s and 1840s edited by the Surtees scholar E. D. Cuming, is reprinted in this book. Once his elder brother had died, as the squire of Hamsterley, he was no longer strapped for cash; but he had got into the habit of writing and could not give up the drug, and turned from journalism to writ- ing his eight novels. Many of his articles were written on automatic pilot, and they show it. At their best, his comic dialogues are as good as anything in Dickens; at their worst they are terrible stuff. There are sam- ples of both the best and the worst in this collection.

He is the greatest and most savage of Victorian satirists. There is no trace of sen- timentality, no Dickensian romanticising of the good old days of the stage coach. The food of coaching inns is terrible, the wait- ers slovens, the prices outrageous — Sur- tees gives us the details of bills just as he wearies us with describing clothing down to the last waistcoat button. After the discom- forts of the stage coach, he regarded rail- ways as a blessing, bringing civilisation to rural society. A resolute progressive, one wonders what he would have thought of the M5. His detestation of smoking dis- plays a savagery and intolerance equalled only by today's health freaks. It is the 'vice of the day', dangerous to the smoker's

health and 'carried to such a height that scarcely any place is free from the contami- nation of its filth'. Better get drunk than smoke a cigar.

Surtees has been scandalously neglected by the panjandrums of Academic Eng. Lit. because he writes about foxhunting, the sport of unlettered barbarians. As this book reveals, his views on foxhunting were both peculiar and prejudiced. His heart was in the provinces; he disapproved of the `swells' of the smart packs, ignorant of houndwork, rowdy exhibitionists, to whom pace was everything. He never liked, and came to positively hate his more successful fellow hunting journalist, Nimrod (C. J. Apperley), snob and lover of 'swells', but a wonderful rider and a humane man. The animus of Surtees was based on envy. Sur- tees was not Apperley's equal as a horse- man, never enjoyed his popularity in hunting circles and was a failure as an MFH. His idol was Ralph Lambton, a provincial master, when Lambton's crash- ing fall confined him to bed for the rest of his life, Surtees took over his pack, but he soon gave it up as he could not stop hounds running after sheep.

Flaunting his personal dislikes in this book, there is a snide attack on a harmless fellow journalist; and his treatment of Nimrod is Unpardonable; so is his anti- Semitism, with his 'cigar-smoking Israelites', his Miss Jewisons"oily hook noses'. Capable of creating characters as powerful and memorable as those of Dick- ens or Balzac, he is a jaundiced genius. His heroes are rogues, redeemed only by their love of foxhunting. Soapy Sponge, a cad who will go to any lengths for a good day's hunting, the immortal James Pigg, a foul- mouthed tippler but who lives for hunting.

His greatest creation is, of course, Jor- rocks, his 'standing dish' as a journalist. This book reveals that the cockney grocer MFH is a more complex character than I had thought. He is a rogue who sells an awful horse to his friend as 'the best horse for ye'; he will butter up a man whom he despises in order to get a good day's shoot- ing; he is not above touting his tea to his field. But he went to Blackfriars Bridge to gain inspiration when he felt 'poetical but the muse would not come'. He dances until dawn reveals the changed complexions of his partners. 'Men, never choose a wife by candlelight'. His evolution as a foxhunter as traced in the articles in this book is of absorbing interest to the historian of fox- hunting. At first he prefers looking at hounds through a telescope on a hill inventing a portable tower for the purpose. He is the ancestor of the enthusiastic car followers with their binoculars. But he later recognises that there's nothing like going `slick away' over open country — provided that 'the leaps are not too large'. He should have been able to hunt with the Dulverton West on a Friday.

Not all the collected journalism in this book is concerned with foxhunting. Surtees visited France, including a visit after the revolution of 1830 that put Louis Philippe on the throne with a 'very unsteady seat'. Paris is a mere shadow of the colourful capital of the dethroned king, Charles X. With few English tourists, restaurants and theatres are half full, Versailles 'dullness reduced to an essence'. He is the first mod- ern travel journalist. Tips about trains and hotel prices abound — he wrote Hints to Railway Travellers (1852). He tells us that it takes three men and a woman to shoe a horse in France; second-hand toothpicks can be bought in the Tuileries, poodles clipped on the Pont Neuf.

These in my mind are wot [Jorrocks is writ- ing] mark the difference of nations more than monarchical forms and wot the observ- ing traveller would be most particular in describing.

Grist to the mill of those modern historians to whom the description of the superficial counts as profundity.

Surtees is no booby squire. An intelligent and thoughtful man, he found rural society tedious, its conversation confined to good runs with hounds and the number of birds massacred. 'English people in general', he writes, 'have no notion of society beyond that of animal gregariousness'. Nine tenths of Christmas mirth is forced. The solution was to import a civilised Frenchman who can liven things up. But he must be treated with champagne. 'Indeed everybody gives champagne now-a-days'. Even as far back as that, it was no longer possible to fob off your dinner guests on arrival with a stiff gin or whisky.

Previous page

Previous page