ARTS

Architecture

Sir Ninian Camper (RIBA Heinz Gallery, till 27 February)

The last Gothic Revivalist

Gavin Stamp

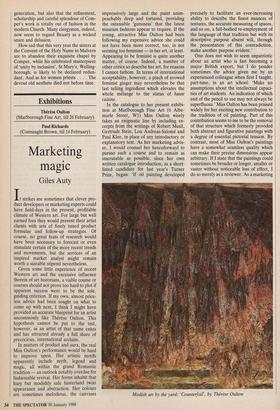

At the height of the Blitz, in Hatch- ett's in Piccadilly, two old men with some- thing in common met for the first and last time. One was C.F.A. Voysey, the Arts and Crafts architect, who had been born in 1857. The other, seven years younger, was the church designer, John Ninian Comper. John Betjeman, who had organised the evening, was delighted to have got these two survivors of the Victorian age together, but the dinner was not really a success. Voysey said hardly a word and, as the only other guest, Sir John Summerson, recalls, 'while young men on leave from the services danced and enjoyed them- selves, the man who held the floor for the whole time was Sir Ninian Comper. He talked and talked and talked, mostly about the proportions, position and stylistic char- acter of the English altar.' Betjeman had initially taken up Comper as a joke but came to admire the work of the charming but rather precious old bore. What is curious, however, is how this Gothic Revivalist was also admired by other young men, among them Kenneth Clark and John Piper, who would not have shared his overriding obsession with the setting, appearance and significance of the altar. One reason for this remarkable cult was that Comper's later work, with bur- nished gold baldacchinos in an austere and pale architectiiral setting, corresponded with contemporary taste. Another was that his earlier intense and highly decorative neo-Mediaevalism was interpreted as a manifestation of English Romanticism. One who did not share this enthusiasm for Comper was Nikolaus Pevsner. As part of their long-running feud, Pevsner responded to Betjeman's gushing praise of Comper's churches by asserting, in his entry in Buildings of England on St Cyp- rian's, Clarence Gate — that dream of Late Mediaeval refinement near Baker Street Station — that 'there is no reason for the excesses of praise lavished on Comper's work by those who confound aesthetic with religious emotions.' Although Betjeman managed to secure a knighthood for the old boy before he finally passed on in 1960, it was Pevsner's moralistic condemnation of historicism that carried the day. Comper is now almost forgotten, except by an older generation of church-crawlers.

Resurrection has come with a small but sumptuous exhibition at the RIBA's Heinz Gallery (21 Portman Square). A gorgeous display of copes and chasubles, banners and mitres, pyxes and morses and other examples of ecclesiastical embroidery and metalwork recalls Pugin's Mediaeval Court at the Great Exhibition. All this, together A dream of Late Mediaeval refinement: St Cyprian's, Clarence Gate with Anthony Symondson's masterly cata- logue essay, explains why Comper was once so respected as a designer within the Church of England.

This exhibition is timely, as Comper's gospel of 'unity by inclusion', that is, the fusion of Gothic and Classic, might well have much to teach post-Modern architects. On the other hand, the decline of the cult of Comper now allows a more balanced appreciation of his achievement compared with that of his contemporaries. Did he deserve all that praise? As a church furnisher he certainly did. He was a fecund master at converting scholarly research into mediaeval art and liturgy into beauti- ful and appropriate craftsmanship.

It is Comper's architecture that raises doubts. His early work continued the Late Mediaeval refinement and sophistication of his master, G. F. Bodley, but it is characterised by a certain preciousness. Although his churches were cleverly plan- ned for Anglo-Catholic ritual, interiors seem more important than exteriors and there is a lack of overall architectural control. They do not display the subtle reinterpretation and development of pre- cedent which distinguishes the churches of his near contemporary, Temple Moore — a great architect whose work deserves to be much better known. Furthermore, Corn- per's later work, of the 1920s and 1930s, seems thin and effete compared with that of Moore's famous pupil, Sir Giles Scott.

The trouble was partly that Comper lived too long, but he — like many of his contemporaries — was also corrupted by the Mediterranean. His early mediaeval vision, inspired by Nuremberg, was trans- formed by the light and colour of the south. And it was not only the classical column that seduced him. The exhibition coyly displays one of those photographs of naked Sicilian boys that he, like his con- temporary in Bodley's office, C.R. Ashbee, discreetly collected. Perhaps it is unfair to blame the Mediterranean: Com- per was so excited by Nijinsky that he used his face in a stained glass window, and the colouring of his needlework changed in response to Bakst's exotic designs for the Ballet Russe. The Edwardian world was more complex and interpenetrating than art history usually suggests.

Even more extraordinary is the story of the National War Memorial of Wales, that piece of Pearl & Dean architecture that stands in Cardiff. Nijinsky being by now unavailable (married and mad), Comper managed to review the crews of two battleships at the Union Jack Club in Waterloo in search of the Greek Ideal. It was found in Fred Barker, a young rating, who was photographed as a model for the naked figure which still stands in Cathays Park. A charming letter from Fred Barker, back at sea, to his unlikely patron is on display in the exhibition.

But this slightly ridiculous side to Com- per is fully transcended by the high serious- ness of his art: an art that was concerned above all with a seemly and authoritative setting for Catholic worship. What, there- fore, is so sad is that all Comper sought to achieve through design combined with painstaking historical research is utterly irrelevant to the modern Church of Eng- land. It is not only that Anglo-Catholics, in their sheep-like following of every Roman fashion, are oblivious to the English litur- gical tradition that so obsessed Comper's generation, but also that the refinement, scholarship and careful splendour of Corn- per's work is totally out of fashion in the modern Church. Many clergymen, indeed, now seem to regard Beauty as a wicked snare and delusion.

How sad that this very year the sisters at the Convent of the Holy Name in Malvern are to abandon their exquisite chapel by Comper, while his celebrated masterpiece of 'unity by inclusion', St Mary's, Welling- borough, is likely to be declared redun- dant. And as for women priests . . . . The devout old aesthete died not before time.

Previous page

Previous page