Mr. JACOB'S Historical Inquiry into the Production and Con- sumption

of the Precious Metals is one of the most curious and Mr. JACOB'S Historical Inquiry into the Production and Con- sumption of the Precious Metals is one of the most curious and important works which has lately issued from the press. The influence of the precious metals on the industry of mankind is acknowledged to be great ; though perhaps the notions respecting the precise mode of its operation were obscure, and undoubtedly the history of its effects had never been traced with accuracy and ingenuity. Mr. HUSKISSON, who had maintained a friendship with Mr. JACOB for more than five-and-twenty years, first put the au- thor on the investigation : it is one of the minor obligations which the country owes to that enlightened statesman. " In subsequent and frequent conversations with Mr. Huskis- son," says the author, " he suggested the utility of taking a more comprehensive view of the subject, and of examining into the sources of those large accumulations of gold and silver which are represented to have existed in the early ages of the world—of their gradual decrease in quantity, and the causes of the disappearance of a large portion of them. These subjects, he thought, might be combined with the state of the prices of commodities, and con- nected with the renewed increase which has arisen from the disco- very of America and the mining operations." This paragraph will convey a general idea of the nature of the work. Perusal alone will satisfy the reader of the patient and extensive research which has been employed, of the many curious particulars elicited, and the important conclusions which are drawn, by the ingenuity of the author, from the facts which his industry has collected. Mr. JACOB'S first volume is occupied with ascertaining, as nearly as existing documents will permit, the amount of treasure collected by difirent individuals at various periods in ancient times, and in thence inferring the total quantity of the precious metals which existed in those times. He then inquires into the sources of this wealth, and with great pains and labour passes in review the accounts which remain of all the mines of antiquity, of their nature and product. This review is carried on to the disco- very of the Western world. Besides calculating the amount of the precious metals, both from the reports of treasure and the sources of increase from mines, an important element of inquiry is the consumption of these metals in the form of coined money from abrasion. This part of the inquiry is in part hypothetical : it is, however, conducted on pretty sure grounds, and the results are very striking. It will be thought almost incredible that, supposing, as there is reason to suppose, if the currency of the Roman empire, at the death of AuGusrus, amounted to three hundred and fifty-eight millions sterling, by wear alone it would have been reduced in the ninth century, when the mines of Hun. gary and Germany began to be worked, to thirty-three millions. The portion of the whole of Mr. JACOB'S investigations, however, which appears to us most deserving of attention, is that which relates to the effect upon Europe of the influx of the precious metals after the discovery of America. The rise of prices consequent upon this discovery, during the first and second cen- turies after it, was enormous, and excited universal discontent and alarm. Ignorant of the truth, reasoners and writers attri- buted it to every cause but the right one,—to forestallers, regraters, to extensive graziers, and above all things to sheep-walks. The popular cry in EDWARD the Sixth's time was against sheep. Sheep was the answer to every complaint against the dearness of provi- sions and the increase of prices. The phenomena must have certainly astonished them: in one century the price of every article was increased fourfold, and the progress of high prices was still more accelerated in the century after. The hardship,wss not, however, in the increase of price, since, if commodities continued to bear the same relative value, it mattered not what price was given for an article, as long as an individual's production equalled his consumption: but the hardship was felt in cases where a man paid high prices in money for his articles of consumption, while his income depended upon revenue fixed in nominal amount; as, for instance, a landlord whose lands were let out in long leases. Many cases of this sort existed, and justified complaint; so that the immediate effect of the importation of the riches of America into Europe produced distress. Other important consequences followed: one of them touched upon by Mr. JACOB. is of high im- portance in the consideration of the constitutional history of England,—it is the effect of this rise of prices upon the power and influence of the English and other sovereigns. We will select e passage on this subject as a specimen of the work. " The several monarchs who ruled in the different divisions of Europe were commonly the largest proprietors of the land, in their dominions, and chiefly subsisted on their produce, which was transferred to then% partly in kind, partly in various feudal services, and partly in money. The portion paid in money was chiefly in the form of fines at the renewal of leases, with small fixed annual rents, which were in many cases almOst nominal, or which became so when the value of money declined, , Ia England. a pepper-torn rent was common ;. but it originated, at a tune when* that spice was of mere than five. hundred times its present NAIL & it

exchanged for silver, and perhaps five thousand times that value when exchanged for corn or wool.

"'In time of war, our monarchs obtained money from their subjects under.various names and pretexts, but in peace chiefly depended on their lands; with some addition from the customs and from the coinage. The litter was made available by Henry the Seventh and Henry the Eighth to an extravagant extent, and by Edward the Sixth till the last year of his reign. In the reign of Mary, her demands were in some measure supplied from the treasures of her husband, Philip of Spain. Elizabeth, who placed confidence in enlightened ministers, was led to avoid the evil of debasing the coin, and in the latter years of her reign placed it on a proper fdoting, which has been continued ever since with slight variations. The rigid frugality she practised, her abstinence from wars, and the high tone of authority which she exhibited to her parliaments, preserved her from pressing on her subjects, who, from a feeling of loyal attachment, were ever ready to satisfy her demands. During these reigns, the income derived by the crown from the lands had been very little increased ; whilst all the expenses of living, whether laid out for foreign or domestic commodities, had been raised to at least four or five times as much as a hundred years earlier. It is, then, evident, that the wealth as well as the power of the crown must have diminished very considerably in the period we are reviewing.

" It does not, indeed, seem improbable that the continued increase of expenditure, whilst a great part of the royal income was stationary, was one of the causes which produced the civil wars in the reign of Charles the First, and at length cost the loss of his life to that unfortunate monarch.

Some other passages, which have struck us by the curiosity of the information they afford, we have selected for the sake of showing the character of the author's manner and style, and in the hope of attracting the attention of thinking minds to the conside- ration of the important topic on which Mr. JACOB has spent so much valuable labour.

THE WEALTH OF THE RICH MEN OF ROME.

4` The fortunes of private individuals may be judged of by a few select notices,to be found in contemporary authors. Crassus is said to have possessed in lands bis militia*, besides money, slaves, and household fur- niture, estimated at as much more. Seneca is related to have pos- sessed ter milliest. Pallas, the freedman of Claudius, an equal sum. Lentulus, the augur, quater . C. C. Claudius Isidorus, although he had lost a great part of his fortune in the civil wars, left by his will four thousand one hundred and sixteen slaves, three thousand six hun- dred yoke of oxen, two hundred and fifty-seven thousand head of other cattle, andin ready money HS. sexcenties§.

" The emperors were possessed of wealth in a proportion commensurate with their superior rank and power. Augustus obtained, by the testa- mentary dispositions of his friends, quotes- decies milliesil. Tiberius left at his death vigesies ae septies milliest which Caligula lavished away in a single year.

" The expenses of the government, and the debts and credits of the most eminent individuals, seem to have been on the same colossal scale. Vespasian, at his accession, estimated the money which the maintenance of the commonwealth required, at three hundred and twenty-two mil- lions nine hundred sixteen thousand six hundred and sixty pounds.

" The debts of Milo amounted to HS. septengenties". Julius Caesar, before he held any office, owed thirteen hundred talents : when, after his prmtorship, he set out for Spain, he is reported to have said, Bis millies et quingenties sibi deesse, ut nihil haberet,—that is, that he was two millions and eighteen thousand pounds worse than nothing. When he first en- tered Rome, at the beginning of the civil war, he took out of the trea- sury to the amount of one million and ninety-five thousand pounds ster- ling, and brought into it, at the end of that war, four millions eight hun- dred and forty-three thousand pounds. He is reported to have purchased the friendship of Curio, at the commencement of the civil contests, by a bribe of four hundred and eighty-four thousand three hundred and seventy pounds; and that of the consul L. Paulus, the colleague of Marcellus, by one of two and hundred seventy-nine thousand five hundred pounds.

"Anthony, on the ides of March, when Caesar was killed, owed three hundred and twenty thousand pounds, which he paid before the kalends of April, and squandered of the public money more than five millions six hundred thousand pounds."

ROMAN FANCY BREAD.•

" The price of bread in Rome, when Pliny lived, seems to have been nearly the same or a little lower than it usually is in our day in London. The Romans made bread of very different qualities and prices. Pliny enumerates four descriptions of them,—viz. Ostrearii, or loaves baked with oysters ; Artolagani, which correspond with our cakes, or rather rolls ; Speustici, from the quick mode of the preparation ; and Artopticii, or those baked in ovens, so called from the kind of furnace in which they were prepared. This last must have been of nearly the same quality as our middle sort of wheaten bread, and was sold, according to the calcu- lation of Arbuthnot, at the rate of three shillings and twopence the peck loaf."

DOMESTIC LIFE OF THE ROMANS.

" The Romans seem to have lived much in public, and to have had very imperfect notions of the enjoyments of domestic life. The object of those who enjoyed great wealth was to attain celebrity and power by means of the populace : the display of magnificence in their dwellings and furni- ture would not have been effective for their chief pursuit. Hence, whilst profuse in that expenditure which could be seen by the public, they were parsimonious in all their private, personal, and domestic arrangements. At an early period, their houses were of wood, and even in the time of Augustus covered with shingles. They had neither chimneys to convey away the smoke, nor glass windows to admit the light and exclude the i cold. An open place in the centre of the roof of the house admitted the rain that fell into a place called impluvium or compluvium, and the light was admitted by the same opening. Even in the villas, where the opulent Romans displayed their greatest domestic luxuries, the barns, stables, wine and oil storehouses, granaries, and fruit-rooms, with the sleeping-places for the agricultural slaves, formed a part of the building in which the pro- prietor resided, and on the top of which was his supping apartment, where he could enjoy the prospect of the surrounding country, without feeling the annoyances which must have affected his senses of smelling and hearing from his stores, and his slaves, and workino. cattle.

" The clothing of even the best families was fabricated in their own houses. The mistress of a family, with the female servants, were em- ployed in spinning and weaving, and conducted the operations in the * 1,614,5831.6x. 8d. sterling. § 484,3751. sterling. t 2,421,8751. sterling. 11 32,291,6661. sterling.

3,229,1661. sterling. ¶ 21,796,8751. sterling.

565,1041.-sterling.

chief apartment (in medio tedium), according to Livy, book i. cap. 57. This kind of industry was thought to be so necessary, that to inculcate it more securely, one part of every marriage procession consisted of females carrying a distaff, a spindle, and wool, to intimate to the bride what was to be her future duty. Augustus himself is said by Suetonius to have worn nothing for his domestic dress but what was manufactured by his wife, his sister, his daughter, and his nieces. The clothing was chiefly of wool ; for though linen was made, and a robe of it (testis lintea) was much valued, it was by no means commonly worn. The only furniture, exclusive of the dishes and vessels for drinking, was a kind of extended couch, which served the purpose both of sitting and sleeping on."

LIVING MONEY.

" Britain especially was so exhausted of the precious metals in the foin of money, that in trafficking, what the Saxon writers call living. money was usual and legal. `This consisted of slaves and cattle of all kinds which had avalue set upon them by law, at which they passed current in the pay- ment of debts and the purchase of commodities of all kinds, and supplied the deficiency of money properly so called." Thus, for example, when a person owed another a certain sum of money, which he had not a suffi- cient quantity of coin to pay, he supplied that deficieney by giving a cer- tain number of slaves, horses, cows, or sheep, at the rate set upon them by law; when they passed for money to make up the sum. All kinds of mulcts imposed by the state, or penances by the church, might have been paid either in dead or living money, as was most convenient; with this single exception, that the church, designing to discourage slavery, refused to accept slaves as money in the pay- ment of penances." In those parts of Britain where coins were very scarce, almost all debts were paid and purchases made with living money.. This was so much the case both in Scotland and Wales, that it is much doubted if any coins were struck in those. countries in the Saxon period.'

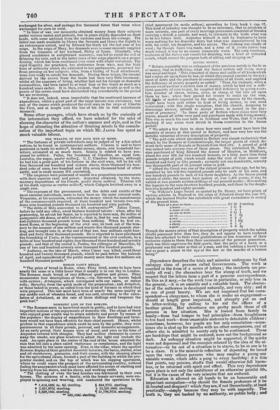

" We select a few facts to show how very small must have been the quantity of money at that period in Britain, and how very low was the- metallic valuation of every description of property. " The gold coin which circulated in Britain was almost exclusively that struck by the Romans at Constantinople, the larger pieces of which de- rived their name of Bezants or Byzants from that city. A pound of gold was coined into seventy-two of these pieces. The celebrated St. Dun- stan purchased of King Edward the manor of Hendon, in Middlesex, about the year 960, for two hundred bezants, or a little more than three pounds weight of gold, which would make the cost of that manor one hundred and forty or fifty pounds ; certainly not one hundredth, scarcely one thousandth part of its present value in gold. "Alfred the Great was one of the richest princes of the age, but he be. queathed by his will five hundred pounds only to each of his sons, and one hundred pounds to each of his three daughters. As the Saxon pound weight of silver, the money here spoken of, was 5,400 grains, it may be valued at two pounds sixteen shillings of our present money; thus making the legacies to the sons fourteen hundred pounds, and those to the daugh- ters two hundred and eighty pounds. "In Wilkins's Leges Saxon. as quoted by Dr. Henry, we have prices of various articles in England in the reign of Ethelred about the year 997, which the learned Doctor has calculated with great correctness in money

£2

16 3 sterling.

• 1 15 2 1

3 5 0

14 1 0

7 01 0

6 2 0

1 101

0 1 2 . 0 0 41

of the present time.

Price of a man or slave a home .

a mare or colt an ass or mule an ox a cow

a swine

a sheep a goat

Though the money prices of that description of property which the nobles chiefly possessed were thus low, they do not appear to have rendered them less attached to their rural gratifications or less tenacious of their exclusive rights to them than their successors of the present generation. Such was their eagerness for field sports, that the price of a hawk or a greyhound was the same as that of a man, and the robbing a hawk's nest was as great a crime in the eye of the law as the murder of a human being."

Previous page

Previous page