Pride of Ownership

By GORDON WILKINS HE motoring writer is often regarded as a pampered individual who rides free of cost in the world's best cars and has little conception of how the poor live. A life which is all steer and vittles, as one of our number has ,phrased it. The picture may be exaggerated, but 1 confess I am sometimes shaken by the equanimity with which learned colleagues speak of engines which had to be completely rebuilt after 25,000 miles, and tyres which were worn out in a fraction of that distance.

So it is with the feelings of a man who has achieved a new ntimacy with the problems which beset his readers that I admit to having bought my new cars with my own money during the last couple of years.

Time was when the purchase of a new car was an event to be discussed with rapturous anticipation for months, but the event seems to have shed some of its excitement. Certainly it is overshadowed in my mind by the knowledge that in buying a car one is contracting to carry a large share of the country's tax burden. One must expect to be lectured and bullied every time anyone has a tweak of conscience about road accidents, all requests for proper roads will he dismissed as wildly unreasonable, and one lines up in the traffic blocks knowing that some of bureaucracy's keenest planners are busy devising new schemes to discourage one from using the car at all.

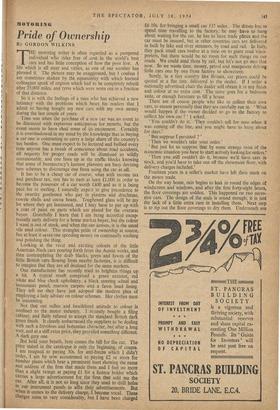

It has to be a cheap car of course; what with income tax and purchase tax, one has to earn at least £1,000 in order to become the possessor of a car worth £400 and as it is being paid for in sterling, I naturally expect to give precedence to the swarthy gentlemen who pay in piastres and drachmae, cowrie shells and cocoa beans. Toughened glass will be my lot where they get laminated, and I may have to put up with a coat of paint on parts which are plated for the overseas buyer. Gratefully I learn that I am being accorded excep- tionally early delivery for a home market buyer, but the colour I want is out of stock, and when the car arrives, it is the usual vile mud colour. This strangles pride of ownership at source, but at least it saves one spending money on continually washing and polishing the thing. Looking at the vivid and exciting colours of the little American Nash cars pouring forth from the Austin works, and then contemplating the drab blacks. greys and fawns of the little British cars flowing from nearby factories, it is difficult to imagine that they arc all destined for the same markets.

One manufacturer has recently tried to brighten things up a bit. A typical result comprised a green exterior, red white and blue check upholstery, a black steering wheel and instrument panel, maroon 'carpets and a fawn head lining. They tell me they have just adopted the modern plan of employing a lady adviser on colour schemes. Her clothes must be interesting.

Not that our sullen and bewildered attitude to colour is confined to the motor industry. I recently bought a filing cabinet, and flatly refused to accept the standard British dark green finish. It clearly embarrassed the suppliers to be dealing with such a frivolous and bohemian character, but after a long wait, and at a stiff extra price, they provided something different. A dark grey one. £0 10s. for bringing a small car 137 miles. The driver has to spend time travelling to the factory, he may have to hang about waiting for the car, he has to have trade plates and the car must be insured, but in other countries cars are delivered in bulk by lake and river steamers, by road and rail. In Italy, they pack small cars twelve at a time on to giant road trans- porters, but there would be no room for such things on our roads. We could send them by rail, but let's not go into that now. So we waste time, money, petrol and manpower driving little cars one by one from factory to showroom.

Surely, in a tiny country like Britain, car prices could be qUoted at a flat rate, delivered to the dealer. If 1 order a nationally advertised chair the dealer will obtain it in any finish and colour at no extra cost. The same goes for a bedroom suite, or enough furniture to fill a house.

There are of course people who like to collect their own cars, to ensure personally that they are carefully run in. ' What would happen if the owner decided to go to the factory to collect his own car '? ' 1 asked.

' You couldn't do it. They couldn't tell for sure when it was coming off the line, and you might have to hang about for days.' ' But suppose r persisted ? '

Then we wouldn't take your order.'

But just let us suppose that by some strange twist of the economic situation you have to start actively looking for orders.'

Then you still couldn't do it, because we'd have cars in stock, and you'd have to take one off the showroom floor, with delivery charges included.' Fourteen years in a seller's market have left their mark on the motor trade.

On the way home, rain begins to leak in round the edges of windscreen and windows, and after the first forty-eight hours, the floor coverings are sodden. This happened on two suces- sive cars. The design of the seals is sound enough; it is just the lack of a little extra care in installing them. Next step is to rip out the floor coverings to dry them. Underneath are the cigarette ends, presumably left by the happy workers on the production line. One car contained three.

Not long ago there was a sudden flash of flame in a famous Continental car factory. Two valuable racing cars were saved by a near miracle and the factory had a narrow escape from a major fire. A visiting British mechanic had descended into a petrol-soaked inspection pit smoking a cigarette.

Such incidents are talked about, and one story leads to another. There is one about an American who bought a British sports car and.was troubled by a persistent rattle in one of the doors. In desperation he pulled the door apart and found a mug of tea inside. Whether it is true or not no longer matters; I have heard it from so many Americans that the damage has been done. The point is that it could only have been a British car; other people don't have tea breaks.

The post-war achievements of the British motor industry have been magnificent, and the ever-rising output figures speak for themselves, but sometimes the suspicion arises that things may be made easier for the man on the production line at the expense of lasting satisfaction for the customer. And we still have something to learn about making cheap cars that are durable. Moulded rubber floor coverings are better than a pretty-looking carpet which is threadbare in three months, and plastic headlinings give greater satisfaction than a cheap cloth, which acts as a filter for London's filthy atmosphere and can make a six-months-old car look as if it had been used for carrying chimney sweeps to work.

Previous page

Previous page