ARTS

Exhibitions

Poporific

Giles Auty

Claes Oldenburg/Coosje van Bruggen: A Bottle of Notes and Some Voyages (Serpentine Gallery till 29 August) Tom Wesselmann (Mayor Rowan till 24 August)

Among those old enough to hold informed opinions on the matter, the populace of the Western world might be divided conveniently into those who did and those who did not find the Sixties culturally stimulating or, in the preferred jargon of the era, 'absolutely fab'. One of my own more lasting memories of the epoch is of my doorbell ringing in the early hours and an otherwise delightful Italian girl announcing from the doorstep, 'I've come to crash at your pad,' in best broken English. Her father, if I remember right, was director of Florence's most famous museum, but the banality and general slackness of the pop/beat culture together with its modes of address —

permeated everywhere. A friend of mine advanced the convincing notion that if the novels of Jack Kerouac were translated into standard English they could be shown to have virtually no content. The age was characterised by shallow, evanescent sty- lishness and threw up such putative artistic heroes as Warhol, Lichtenstein, Olden- burg and Wesselmann. The latter two are with us this summer in Britain, giving those whose memories do not extend back a quarter of a century a chance to see what all the fuss was about.

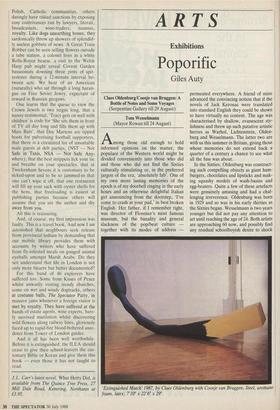

In the Sixties, Oldenburg was construct- ing such compelling objects as giant ham- burgers, chocolates and lipsticks and mak- ing squashy models of wash-basins and egg-beaters. Quite a few of these artefacts were genuinely amusing and had a chal- lenging irreverence. Oldenburg was born in 1929 and so was in his early thirties as the Sixties began. Wesselmann is two years younger but did not pay any attention to art until reaching the age of 24. Both artists are approaching 60 now, and possibly find any residual schoolboyish desire to shock `Extinguished Match' 1987, by Claes Oldenburg with Coosje van Bruggen. Steel, urethane foam, latex; 7'10" x 22'6" x 29". becoming something of a strain.

The Pop Art movement has obvious historical links with Dada. No doubt ideas of shocking the bourgeoisie and mocking established notions of high culture nurture delicious feelings of rebelliousness in young artists. Yet such attitudes are no more than a pose because the supposed adversaries have been unreal and chimeric- al for decades now. As the eminent histo- rian E.H. Gombrich pointed out at the time: 'Today the problem is rather that the shock has worn off and that almost any- thing experimental seems acceptable to the press and the public. If anybody needs a champion today it is the artist who shuns rebellious gestures. . . .' Precisely. Once the notion of shock is removed, a lot of Pop Art tends to look pretty tame and tawdry. The defiant gesture has to get bigger and, if possible, sillier to titillate the jaded appetite. Oldenburg continues to enlarge the scale of his banal objects and works on these co-operatively now with a charming collaboratrice Coosje van Brug- gen.

In Oldenburg's favour he has often displayed a kind of whimsical poetry; yet the art of making gestures remains danger- ously arbitrary. If artistic choice falls on a giant toothbrush, hamburger or handsaw — all Oldenburg projects — then why not a mammoth razor-blade, lamb kebab, or brace and bit? There is little doubt that somebody, somewhere, would wish to buy or commission such objects as his particu- lar investment in radical chic. Aside from a giant pencil, electrical plug, apple core, spent match and other Oldenburg famil- iars, the present Serpentine show contains many small-scale models or drawings for projects, most of them unrealised. Perhaps it is diverting to muse on replacing Nel- son's column with a giant gear-lever or rear-view mirror, yet to make somewhat self-conscious memoranda about such con- ceits, and then exhibit them, smacks of something a touch too self-important to make me laugh.

Wesselmann's paintings and collages at Mayor Rowan Gallery (31A Bruton Place, W1) — with a major overspill at Mayor Gallery (22A Cork Street, W1) — are generally more obvious and less poetic than Oldenburg's artefacts. If he had been born at a different time, one doubts Whether Wesselmann would have become a painter at all; indeed, in his youth he dreamed of owning a sports store. There is a commercial slickness to many of his collaged images of bland consumer pro- ducts: tinned foods, ice creams, cans of beer and so forth. Soon woman joins the list of consumables to be unwrapped, used and presumably discarded. Wesselmann is an artist given to long series and labels his works accordingly. By 1967 his 'Great American Nude' sequence had reached number 92 and also some kind of zenith, or nadir, of Pop eroticism. Wesselmann's ability to compose paintings had matured somewhat by this time, but not the fetish- ism of his priapic obsessions. In the past few years, Wesselmann has turned to the medium of painted metal cut-outs, but the subject remains the languors of pre- or post-coital women. The treatment he em- ploys is a curious combination of Matisse and Walt Disney.

Consuming passion or consumer dur- able? Wesselmann's images of woman enshrine the American male's apparent yearning for depersonalised couplings.

Previous page

Previous page