THE END OF THE AFFAIR

Oliver Walston looks back at his mother's relationship with Graham Greene

In newly published biographies of Graham Greene, Catherine Walston, his god-daugh- ter, is depicted as the woman who fulfilled the writer's bizarre sexual fantasies during their 13 year adulterous affair. In this article, her son responds to what he describes as `cheapened and much distorted' accounts of his mother's 42-year marriage to Harry Wal- ston, one of England's richest men.

EVERY LITTLE boy thinks his mother is the most beautiful woman in the world and I was no exception. The difference is that even today when, as a middle-aged man, I look at the photographs of her which have been recently published I have no reason to change my mind. And this is in spite of the fact that for the last decade of her life she was a very sick lady indeed. The effort and excitement of burning her candle not just at both ends but also in the middle must have taken a terrible toll.

The strange thing is that even in her final days, when my mother's mind wan- dered and her body could scarcely move, the men in her life remained constant and devoted. Chief among these was, of course, my father. They had been married 42 years earlier and — in spite of the sort of pressures which would have smashed most marriages — they shared a family, a home and a bedroom.

Another man also seemed still to care about her. Graham Greene lived 800 miles away in a small apartment overlooking the port of Antibes. At irregular intervals let- ters used to arrive addressed to my mother written in that strange spidery writing which was, like a fingerprint, unique to Greene. I had first met him as a small boy of seven when, in the spring of 1948, my mother told me that we were going to Italy to stay with Graham. Together with my younger brother and sister and Twinkle, our nanny, we flew off from Northolt to Naples. For three months we sat in the sunshine of Capri, playing in the walled garden of Greene's white-painted villa. In the mornings we were confined to the fur- thest corner of the garden and told to be quiet because 'Graham works in the morn- ing and he doesn't like any noise'. In the evenings we would stroll down to the piaz- za of Anacapri and eat a dish which, for a boy who lived in dreary, rationed post-war England, was unspeakably exotic. It was called a pizza. On rare occasions we would go on expeditions, sometimes by boat to the Blue Grotto and sometimes to the other side of the island to visit Gracie Fields and her husband, who had settled there.

Greene himself was a distant figure who appeared to tolerate children but never to enjoy us. He must have looked on us as a price he had to pay to have my mother's company. And this in itself was strange since my mother, for all her energy, excite- ment, generosity and unpredictability, was never a good mother in the accepted sense of the word. She liked her children in short sharp bursts between the exciting episodes in her life. Twinkle, in whom my mother used to confide at great length, did all the things which most mothers take for granted: bedtime reading, sewing on Cash's name tapes, listening to our fears and triumphs. My mother would appear, preceded by a bow wave of Guerlain's Mitsouko perfume, and enthral us with an account of where she had been or was about to go. Throughout our stay on Capri it never occurred to me that Greene was anything more than a good friend of my mother's. The complexities of human relationships, still more the concept of adultery, meant nothing to me.

As Easter approached we left Capri and drove to Rome where — as usual with my mother — we stayed at the best hotel in town, the Hassler at the top of the Spanish Steps. Those were the days of currency restrictions and so we were unable to afford any meals in the hotel. Every morn- ing Greene would lead a procession of three adults and three children down the Spanish Steps to a coffee house where I would have a cup of hot chocolate topped with an unimaginable amount of whipped cream. On the way back we would stop to gaze into the windows of the Perugina chocolate shop and marvel at big chocolate Easter eggs which back home in England would have used up all our sweet rations for a year or more.

In the years which followed, Greene's affair with my mother settled down into something like comfy normality. I saw no signs of the tension between my parents to which Greene's letters refer. To me he was just one of a coterie of friends who came down to Thriplow most weekends to get away from London, sit in the sunshine, read the papers and drink a bit. Whatever passed between my mother and father did so behind closed doors and not a ripple nor an echo ever penetrated the nursery.

During this period my mother travelled the world with Greene, going to the Caribbean to visit Noel Coward, to Viet- nam where they smoked opium and, most frequently, to a small cottage on Achill Island off the west coast of Ireland. My father had by then come to terms with Greene and, although they never had a warm relationship, at least tolerated his presence at Thriplow. By then my father was making a gradual transition from farm- ing to politics, spending more time in Lon- don where he had a small house above Lock's the hatters in St James's Street. He too had his fair share of women friends with whom he used to wander round France, staying in simple hotels and eating at expensive restaurants.

After their travels my parents would return to Thriplow like homing pigeons after a mission. There they found content- ment and a quietness which must have con- trasted starkly, with the non-stop action of their lives away from home. The letters between them at this period show an eerily friendly relationship which seemed to have no secrets and created no jealousy. My mother would write long letters from Italy in which she would describe the weather on Capri, how many words Graham had writ- ten that day and whether or not he was passing through one of the fits of melan- cholia which punctuated his life like storms in the Bay of Biscay. Her descriptions were graphic but everyday, almost as if she was describing a day's outing to Brighton with an old friend. My father would reply with news of the farm and the family and would end by saying how much he was looking forward to collecting her from Heathrow the following week.

As I grew older I began to look on Greene as more than just a weekend visi- tor. One day at my prep school I was leaf- ing through Picture Post when my mother's face jumped out of the pages. There she was in her inevitable mink coat standing beside Graham at some theatrical event in Brighton with Noel Coward. I felt half- embarrassed and half-proud that my mum was famous — or at least had made it to Picture Post, which came to the same thing.

By then Greene had bought the flat next door to ours in St James's Street, and when we moved from there to Albany, he moved too. Very occasionally, when Greene was abroad and our apartment in Albany was too full, my mother would use Graham's flat as overflow accommodation and I was given a sleeping bag and told to doss down on the floor. Those were excit- ing nights. I would count the miniature whisky bottles on the mantelpiece, and, after drawing the curtains, would put Eartha Kitt on the record player and read Greene's copy of Fanny Hill, which my mother had told me was pornographic. And perhaps it was, but to a pubescent like

me Eartha Kitt had an infinitely more dis- turbing effect.

The last trip I made with Greene was in the summer of 1956. The previous winter, while skiing in Gstaad with my family, I had read in the continental edition of the Daily Mail that Grace Kelly was to be mar- ried to Prince Rainier of Monaco. For the past two years I had suffered from an acute adolescent crush on the blonde actress from Philadelphia, and went run- ning to my mother to break the dreadful news. Any normal mother would have smiled benignly and asked me if I had done my homework. My mother was not such a person. She immediately booked a call to England and, a few hours later, was speaking to Mrs Young, who at the time was a secretary shared by my father and Greene. Mrs Young was instructed to book rooms at the Hotel de Paris in Monte Carlo and to make the necessary plane reservations.

Six months later Greene, my mother and I flew to Paris where, after a lunch of mate aux amandes at the Restaurant Voltaire on the Quai Voltaire, we caught the train for Monte Carlo. We stood among the crowds which lined the proces- sion route and saw the open Rolls-Royce take the couple to and from the cathedral. My agony was heightened by the discovery that Grace Kelly had brought her pet poo-

dle from America to sleep at the foot of the marital bed. The dog was called Oliver. It was more than I could bear.

By then I was an acne-infested Etonian who should have been wise to the ways of the world. Maybe I should have noticed that Greene and my mother shared a room. Maybe I should have disapproved. Maybe I should have sniggered. I did none of these things. I was not only innocent but I had also grown used to Greene's presence over the past decade. He might not have been part of the furniture but he certainly was part of the landscape.

Yet even the landscape changes, and gradually Graham Greene faded from our lives. I would like to pretend that I noticed a great change in my mother. But at the time I was far too obsessed with my adoles- cent traumas to detect the shock. Looking back, it is plain that my mother's long and painful decline started at almost exactly the time that she and Greene parted in 1959.

To all outward appearances she must have seemed like the same bewitching, exciting, unpredictable, shocking and sexy woman she had always been. She still trav- elled widely, entertained lavishly and most important for her — was still able to turn every male head when she walked into a crowded room.

Her circle of friends had been changing imperceptibly throughout the 1950s and now became more and more centred on an assortment of Catholic priests who used Newton Hall (to where we had moved when the army finally vacated it) as a com- bination of rest home and restaurant. Most of these were poor, tired men whose lives were humdrum, celibate and spartan. Few of them were able to cope with a hostess whose perfume pervaded the house like secular incense and whose scarlet toenails and flashing eyes must have made Jezebel seem domesticated.

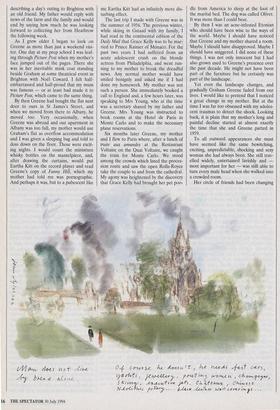

But it was not simply my mother's physi- cal presence that all men found so irre- sistible. Thanks to Greene and his friends, she had read widely and voraciously so that she was as happy talking about the novels of Thomas Mann as the theology of Thomas Aquinas. John Rothenstein, who was then the director of the Tate Gallery, had continued her education by introduc- ing her to the world of contemporary artists. As a result it was my mother rather than my father who used to visit Henry Moore with brown envelopes full of five- pound notes and return with a small bronze and a gouache. Eventually, armed with her own innate good taste and my father's chequebook, she managed to build up an extraordinarily good collection of modem British paintings. My mother was, in other words, anything but a bimbo. No wonder those tragic priests must have discovered a whole new dimension to temptation for which their spiritual training left them totally unpre- pared. But in her own way my mother was equally unprepared for life in general and middle age in particular. One day, coming home from the flat which she kept in Dublin as her very pri- vate refuge, she slipped and broke her hip. Within a few months she changed from being hyperactive to a near cripple who walked unsteadily with a stick. Alcohol, which had long been important in her life, now became an obsession. Eventually even the priests drifted away and she sank slow- ly but inevitably into a half-life of pain and depression. Very occasionally, when an old friend or a letter from Greene arrived, she would rouse herself, sit up in bed and for a few hours one could see faint signs of the sparkle which had illuminated so many lives. Throughout this final tragic period one man stood by her and slept by her. My father, in spite of everything, remained constant in his own way. During her last night I sat in the hospital room while my father stroked her hand and talked quietly about the old days. With tubes sticking through her papery grey skin, she drifted in and out of consciousness. From time to time she would open her eyes, smile an exhausted smile, and close them again. Towards dawn she died and my father sat silent. Only then was their marriage finally over.

Previous page

Previous page