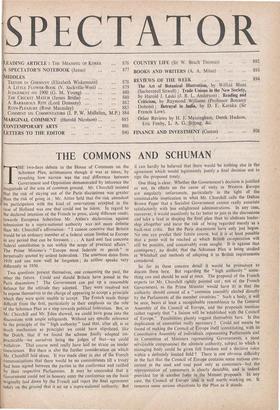

THE COMMONS AND SCHUMAN

HE two-days debate in the House of Commons on the Schuman Plan, acrimonious though it was at times, by revealing how narrow was the real difference between Government and Opposition demonstrated by inference the

magnitude of the area of common ground. Mr. Churchill insisted that the risk of staying out of the Paris discussions was greater than the risk of going in ; Mr. Attlee held that the risk attendant on participation with the kind , of reservations accepted in the case of Holland was one that could not be taken. In regard to the declared intention of the French to press, along different roads, towards European federation Mr. Attlee's declaration against submission to a supra-national authority was not more definite than Mr. Churchill's affirmation : " I cannot conceive that Britain would be an ordinary member of a federal union limited to Europe in any period that can be foreseen. . . . A hard and fast concrete federal constitution is not within the scope of practical affairs." The Prime Minister's " Europe must federate or perish " is Perpetually quoted by ardent federalists. The assertion dates from 1939 and can now well be forgotten ; its author speaks very differently in 1950.

Two questions present themselves, one concerning the past, the other the future. Could and should Britain have joined in the Paris discussions ? The Government can put up a reasonable defence for the attitude they adopted. They were resolved not to expose themselves to the charge of appearing to accept a principle Which they were quite unable to accept. The French made things- difficult from the first, particularly in their emphasis on the role of the Schuman Plan as a step towards political federation. But, as Mr. Churchill and Mr. ,Eden showed, we could have gone into the discussions with ample safeguards. Without any specific reference to the principle of the " high authority " (and that, after all, is as much mechanism as principle) we could have stipulated, like the Dutch, that if we found the scheme finally adopted im- Practicable—we ourselves being the judges of that—we could withdraw. That course need really have laid no strain on tender consciences. But there is also the further consideration on which Mr. Churchill laid stress. It was made clear in one of the French communications that there would be no commitments till a treaty had been signed between the parties to the conference and ratified by their respective Parliaments. It may be contended that a Government could not in honesty enter the conference on the basis originally laid down by the French and reject the final agreement solely ou the ground that it set up a supra-national authority.' But

it can hardly be believed that there would be nothing else in tip agreement which would legitimately justify a final decision not to sign the proposed treaty.

One thing is clear. Whether the Government's decision is justified or not, its effects on the cause of unity in Western Europe are singularly unfortunate, particularly in the light of the unmistakable implication in what Mr. Churchill calls the Dalton Brown Paper that a Socialist Government cannot really associate satisfactorily with less enlightened administrations. In any case, moreover, it would manifestly be far better to join in the discussions and take a lead in shaping the final plan than to abdicate leader- ship altogether and incur the risk of being regarded merely as a back-seat critic. But the Paris discussions have only just begun. No one can predict their future course, but it is at least possible that a point will be reached at which British co-operation will still be possible, and conceivably even sought. It is against that contingency, no doubt, that the• Schuman Plan is being studied in Whitehall and methods of adapting it to British requirements considered.

So far as these concern detail it would be premature to discuss them here. But regarding the " high authority " some- thing can and should be said at once. The proposal of the French experts (as Mr. Churchill rightly pointed out ; not of the French Government, as the Prime Minister would have it) is that the authority should consist of a " common assembly elected directly by the Parliaments of the member countries." Such a body, it will be seen, bears at least a recognisable resemblance to the General Assembly of the Council of Europe, and the proposals mention rather vaguely that " a liaison will be -established with the Council of Europe." Possibilities plainly suggest themselves here. Is this duplication of assemblies really necessary ? Could not means be found of making the Council of Europe itself (constituting, with its Consultative Assembly of individuals representing Parliaments and its Committee of Ministers representing Governments, a most serviceable compromise) the ultimate authority, subject to which a managing body could be given full freedom and a decisive voice within 'a definitely limited field ? There is one obvious difficulty in the fact that the Council of Europe contains some nations con- cerned in the steel and coal pool only as consumers—but the representation .of consumers is clearly desirable, and is indeed provided for in another form in the Monnet proposals. In any case, the Council of Europe idea is well worth working on. It removes some serious objections to the Plan as it stands.

Previous page

Previous page