Computer wedding

JOHN BULL

Elliott-Automation has been saved. That must rank as one of the most heartening pieces of economic news this year. The £41 million bid from English Electric, together with Industrial Reorganisation Corporation backing, provides a most acceptable solution to Elliott's problems.

Elliott-Auto has not run out of ideas—nor customers. It has run out of cash. To see this is to understand the essential logic of the English Electric merger and to comprehend the law-jaw' rather than 'war-war' in which the major electronics companies are indulging at the moment. Elliott-Auto's 1966 report, issued at the end of May, was a depressing document It showed that overdrafts had shot up from £6.65 million to £10.25 million and that the company proposed to deal with the situation by issuing Elf million or so of preference shares. This is an expensive way to raise a puny amount of fresh capital. But there was no alternative. The balance sheet would not support another debenture or loan stock issuee. And it is doubtful whether the market would have swallowed a rights issue in ordinary shares. That report hoisted a danger signal over the company and, thank goodness, it hat been answered. Elliott would have, probably survived a little longer by itself if it had not been for the can- cellation of the TSR 2, the P 1154 and the HS 681. Faced with the collapse of an im- portant part of one's order book, the usual reaction is to trim back staff and capacity accordingly. Not so Elliott-Auto: Sir Leon Bagrit decided that his design teams must be preserved intact until new work came along. It was an uncomfortably long time before the gaps were filled. Meanwhile, profits plum- metted. At the same time, Elliott, like its com- petitors, was having to finance its entry into microelectronics, an expensive business requir- ing millions of pounds of capital, but a development of the utmost importance. Micro- circuits are more than components, they are now the heart of an advanced product.

It was not, however, an easy merger to arrange. The snag was that Elliott's share price refused to fall to a realistic level. It was the glamour stock of the market in the late 1950s and early 1960s, and shareholders could not bring themselves to take a hefty loss on their holdings in a company which continued to do, technically, all the right things—selling com- puters to Russia, planning centres, putting equipment in American planes, providing traffic control for Madrid and Barcelona. If you raised the subject across a merchant bank lunch table, there was a polite shrug: 'nothing could be done until the share price climbed down.' And, indeed, it is reported that Sir Leon Bagrit has been engaged in quite a few rounds of abortive talks with possible partners.

Luckily there was the Industrial Reorgani- sation Corporation on the sidelines. This was just the situation for which it was created. If it could not help, then Sir Frank Kearton and

Mr Ronald Grierson would have to reckon that the IRC was, as many suggested, without a role. They rose to the occasion. The tree is pro- viding a £15 million eight-year loan, interest-free for the first two years and at 8 per cent there- after. The loan also grants !RC conversion rights into English Electric equity to enable the IRC to make a respectable return on its investment (in effect, to make up for the two years without interest). The IRC loan turned an unattractive marriage into an attractive one. The deal itself turns English Electric into a most formidable company, one which can rank with the biggest in the United States, Germany and Japan.

Sales will total nearly £400 million a year. The product range includes electric transmis- sion networks, control gear for, say, steel mills, immensely sophisticated instrumentation (the sine qua non of any automation exercise), turbo-generators, colour Tv cameras, head-up equipment for aircraft, computers of all sizes and so on; the list is endless and impressive. Its importance is that it indicates that Britain has a giant-sized electrical company, able to produce a package deal for anyone, anywhere.

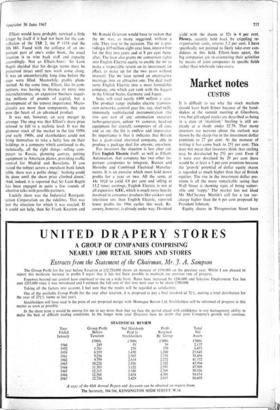

For investors the situation is less clear cut. First English Electric itself: as well as Elliott- Automation, that company has two other im- portant companies to integrate, Ruston and Hornsby and Combined Electrical Manufac- turers. It is an exercise which must hold down profits for a year or two. All the same, at 44s 103d to yield 4.9 per cent and selling at 13.2 times earnings, English Electric is not at all expensive. GEC, which is much more heavily involved in consumer products like cookers and television sets than English Electric, reported lower profits for 1966 earlier this week. Re- covery, however, is already under way. Dividend

yield with the shares at 52s is 4 per cent. Plessey, recently held back by crippling re- organisation costs, returns i5.2 per cent. I have specifically not pointed to likely take-over can- didates in this field. Elliott-Auto apart, the big companies are re-orientating their activities by means of joint companies in specific fields rather than wholesale take-overs.

Previous page

Previous page