Urban degeneration

Ross Clark

IT's summer, and urban England reverberates once more to the traditional sound of baseball bat on polypropylene riot shield. The great inner-city riot is back with a vengeance, rekindling memories of Toxteth, Lord Scarman and a punk-rock group called the Specials who, much to the annoyance of local residents, built their reputation on a pop video depicting a burnt-out Coventry.

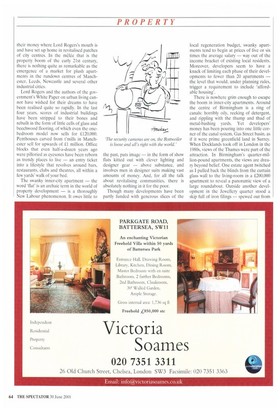

Bradford, Oldham and now Burnley: given the copycat nature of riots, those who live in the centres of other industrial cities would do well to pray for rain — the one thing which, once the CS gas canisters and appeals for calm from local churchmen have run their course, tends to send the British rioter running for cover, But there is one group of people who must be feeling more anxious than any other: the new urban classes who have put their money where Lord Rogers's mouth is and have set up home in revitalised patches of city centres. In the mêlée that is the property boom of the early 21st century, there is nothing quite as remarkable as the emergence of a market for plush apartments in the rundown centres of Manchester, Leeds, Newcastle and several other industrial cities.

Lord Rogers and the authors of the government's White Paper on urban living cannot have wished for their dreams to have been realised quite so rapidly. In the last four years, scores of industrial buildings have been stripped to their bones and rebuilt in the form of little cells of glass and beechwood flooring, of which even the onebedroom model now sells for £120,000. Penthouses carved from Cali% in Manchester sell for upwards of £1 million. Office blocks that even half-a-dozen years ago were pilloried as eyesores have been reborn as trendy places to live — an entry ticket into a lifestyle that revolves around bars, restaurants, clubs and theatres, all within a few yards' walk of your bed.

The swanky inner-city apartment — the word 'flat' is an archaic term in the world of property development — is a thoroughly New Labour phenomenon. It owes little to the past, puts image — in the form of show flats killed out with clever lighting and designer gear — above substance, and involves men in designer suits making vast amounts of money. And, for all the talk about revitalising communities, there is absolutely nothing in it for the poor.

Though many developments have been partly funded with generous slices of the local regeneration budget, swanky apartments tend to begin at prices of five or six times the average salary — way out of the income bracket of existing local residents. Moreover, developers seem to have a knack of limiting each phase of their developments to fewer than 20 apartments — the level that would, under planning rules, trigger a requirement to include 'affordable housing'.

There is nowhere grim enough to escape the boom in inner-city apartments. Around the centre of Birmingham is a ring of canals: horribly oily, reeking of detergent, and rippling with the thump and thud of metal-bashing yards. Yet developers' money has been pouring into one little corner of the canal system. Gas Street basin, as if it were prime greenfield land in Surrey. When Docklands took off in London in the 1980s, views of the Thames were part of the attraction. In Birmingham's quarter-million-pound apartments, the views are dreary beyond belief. One estate agent twitched as I pulled back the blinds from the curtain glass wall to the living-room in a £200,000 apartment to reveal a panoramic view of a large roundabout. Outside another development in the Jewellery quarter stood a

skip full of iron filings spewed out from

the factory next door. And yet both developments were selling fast — even if not all are being snapped up by the young and trendy buyers that the developers hope for. One confided to me that he had conceived his scheme with thirty-something clubbers in mind, and had been taken aback by the numbers of retired people asking whether the building had a stairlift.

The market for swanky apartments in provincial city centres has yet to claim victims. Prices have accelerated in line with London levels — in spite of the housing market in the cities around them being subdued. The inflation in prices has allowed developers to bring in ever-more fashionable designers. There is a body of buyers who refuse to be seen in anything but the latest apartment: the old flat is discarded like a pair of slightly scuffed shoes, sold on at a healthy profit after no more than a year or two's occupation. Investors — in many developments more than half the properties sell to buyers looking for a quick profit rather than for somewhere to live --have been making a killing buying apartments off-plan, before the block is actually built, and selling them on the moment they are completed.

Yet there is something not entirely sensible about the rush to buy flats in rundown areas. Should recession strike, this is one market that could collapse big time. Unlike in London where the prices of modern apartments in Docklands are held aloft by the property inflation that has afflicted the entire metropolitan area since the mid-1990s, in many provincial cities the apartment market is an edifice built in some very shaky surroundings. For all the money being spent in isolated pockets, the state of the inner-cities is poorer now than it was during the era of Lord Scarman. Not two miles away from Manchester's first £1 million apartment are areas where terraced houses sell for under £10,000, and where prices are still falling. Speculators are active in parts of Salford, though not because they think it is on the up: rather because they are hoping that by boarding up their properties they will bring down the area sufficiently to provoke the local authority to compulsory-purchase their houses. Although local authorities are supposed to pay only market value for properties compulsorily purchased, if you buy in bulk, you might be able to make a tidy profit.

In the Danes House area of Burnley, the location of this week's rioting, two-up twodowns were selling for £25,000 each in the late 1980s. Now, typically, they sell for £10,000, and the houses are three quarters empty. In 1999 one investor bought 29 of the houses for a total of £79,000. Made of solid stone, they cost less than the materials from which they were built.

The new urbanites can still afford to ignore the property underclasses at their feet. But a summer of rioting will not do much to help. 'Negative Equity II, coming to a street near you soon', said one of Labour's election posters. It is just possible that with so much resting on mortgaged apartments in Labour's heartlands of the northern inner-cities, they might just come to regret those words.

Previous page

Previous page