Exhibitions 2

Carlton House: The Past Glories of George IV's Palace (The Queen's Gallery, till 11 January 1992)

Princely prodigality

Ruth Guilding

The climate of opinion has changed since the days when George IV was gener- ally described as 'a dissolute and drunken fop'. The impact of this exhibition will alter it still further. For all his vices, King George was never less than regal and sometimes positively imperial in his demeanour; he reigned in critical days and handed on a great inheritance to his suc- cessor. Our present monarch sees no incongruity in hosting this exhibition at Buckingham Palace.

A handsome and scholarly catalogue accompanies the exhibition, compiled by the Queen's 'good men and true', who are the surveyors of her collections. Some pains have been taken to emphasise that this is essentially an exhibition about Carlton House, rather than about Prinny, so connoisseurs of the salacious biographi- cal anecdote will be disappointed — I have read the catalogue quite through and there are not any. But a thoughtful perusal of the exhibits on show reveals the subtle and complex character of their owner.

Of Carlton House itself nothing now remains, except eight Corinthian columns re-used in the flanking entrances of the National Gallery, and some other architec- tural salvage incorporated at Windsor. The palace's lavishly decorated interiors were immortalised for posterity, however, in a series of watercolour drawings from W.H. Pyne's The History of Royal Residences, published in 1819, and in the diaries and correspondence of the guests entertained there. In 1811, Lord Colches*er recorded that at a banquet for 3,000 guests in hon- our of George III's birthday the centre- piece of the banqueting table was a stream containing live goldfish, feeding into a cir- cular lake surrounded by perfume-burners and an architectural colonnade; while the dazzling effects of myriad candles, oil lamps and crystal chandeliers put Lady Elizabeth Fielding in mind of Nahomet's Paradise .. . the glitter of spangles and finery, of dress and furniture that burst upon you were quite eb/otiissaa. Sadly, the Queen's Gallery offers no resources with which to convey these effects — walls lined with scarlet hessian and subdued spot-light- ing do the furniture and pictures on display no favours, although the central show-case

whose modern carcase has been disguised in scarlet tenting, held aloft on golden spear-shafts, makes an attempt at theatre.

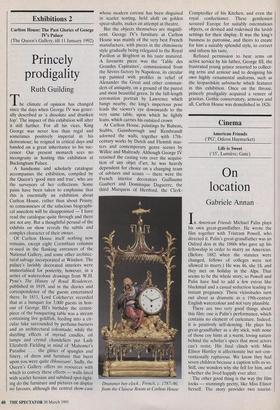

But the objects themselves are magnifi- cent. George IV's furniture at Carlton House was mainly of the very best French manufacture, with pieces in the chinoiserie style gradually being relegated to the Royal Pavilion at Brighton as his taste matured. A favourite piece was the 'Table des Grandes Capitaines', commissioned from the Sevres factory by Napoleon, its circular top painted with profiles in relief of Alexander the Great and other comman- ders of antiquity, on a ground of the purest and most beautiful green. In the full-length coronation portrait by Lawrence which hangs nearby, the king's imperious pose leads the viewer's eye downwards to the very same table, upon which he lightly leans, which carries his outsized crown At Carlton House, paintings by Ruhens, Stubbs, Gainsborough and Rembrandt adorned the walls, together with 17th- century works by Dutch and Flemish mas- ters and contemporary genre scenes by Wilkie and Mulready. Although George IV retained the casting vote over the acquisi- tion of any objet d'art, he was heavily dependent for choice on a changing team of advisers and scouts — there were the French interior decorators Guillaume Gaubert and Dominique Daguerre, the third Marquess of Hertford, the Clerk- Drummer boy clock , French, c. 1787-90, from the Chinese Room at Carlton House Comptroller of his Kitchen, and even the royal confectioner. These gentlemen scoured Europe for suitably ostentatious objects, or devised and redevised the lavish settings for their display. It was the king's business to patronise, and theirs to create for him a suitably splendid style, to correct and inform his taste.

Refused permission to bear arms on active service by his father, George III, the frustrated young prince resorted to collect- ing arms and armour and to designing his own highly ornamental uniforms, such as the leopardskin sabretache which features in this exhibition. Once on the throne, princely prodigality acquired a veneer of gravitas. Gothic conservatory, armoury and all, Carlton House was demolished in 1826.

Previous page

Previous page