FINE ARTS SPECIAL

Whose i art is it anyway?

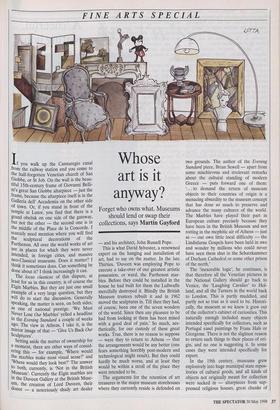

Forget who owns what. Museums should lend or swap their collections, says Martin Gayford If you walk up the Cannaregio canal from the railway station end you come to the half-forgotten Venetian church of San G. 'ebbe, or St Job. On the wall is the beau- tiful 15th-century frame of Giovanni Belli- nes great San Giobbe altarpiece — just the frame, because the altarpiece itself is in the Galleria dell' Accademia on the other side of town. Or, if you stand in front of the temple at Luxor, you find that there is a grand obelisk on one side of the gateway, but not the other — the second one is in the middle of the Place de la Concorde. I scarcely need mention where you will find the sculptural decorations of the Parthenon. All over the world works of art are in places for which they were never intended, in foreign cities, and massive neo-Classical museums. Does it matter? I think it sometimes does. Can something be done about it? I think increasingly it can. The locus classicus of this dispute, at least for us in this country, is of course the Elgin Marbles. But they are just one small example of a very large question, but they will do to start the discussion. Generally speaking, the matter is seen, on both sides; as one of national prestige. 'We Must Never Lose Our Marbles' yelled a headline in the Evening Standard a couple of weeks ago. The view in Athens, I take it, is the mirror image of that — 'Give Us Back Our Sculptures'.

Setting aside the matter of ownership for a Moment, there are other ways of consid- ering this — for example, 'Where would the marbles make most visual sense?' and Where would they look best?' The answer to both, currently, is 'Not in the British Museum'. Currently the Elgin marbles are in the Duveen Gallery at the British Muse- um, the creation of Lord Duveen, their donor — a notoriously shady art dealer — and his architect, John Russell Pope.

This is what David Sylvester, a renowned expert on the hanging and installation of art, had to say on the matter. In the late Thirties, `Duveen was employing Pope to execute a take-over of our greatest artistic possession, or ward, the Parthenon mar- bles. Before they could be installed in the house he had built for them the Luftwaffe mercifully destroyed it. Blindly the British Museum trustees rebuilt it and in 1962 moved the sculptures in. Till then they had, of course, been one of the seven wonders of the world. Since then any pleasure to be had from looking at them has been mixed with a good deal of pain.' So much, aes- thetically, for our custody of these great works. True, there is no reason to suppose — were they to return to Athens — that the arrangements would be any better (one fears something horribly post-modern and technological might result). But they could hardly be much worse, and at least they would be within a stroll of the place they were intended to be.

The arguments for the retention of art treasures in the major museum storehouses where they currently reside is defended on two grounds. The author of the Evening Standard piece, Brian Sewell — apart from some mischievous and irrelevant remarks about the cultural standing of modern Greece — puts forward one of them: `... to demand the return of museum objects to their countries of origin is a menacing absurdity to the museum concept that has done so much to preserve and advance the many cultures of the world. The Marbles have played their part in European culture precisely because they have been in the British Museum and not rotting in the mephitic air of Athens — just as — our own little local difficulty — the Lindisfarne Gospels have been held in awe and wonder by millions who could never have seen them shut in the Schatzkammer of Durham Cathedral or some other prison of the north.'

The 'inexorable logic', he continues, is that therefore all the Venetian pictures in the National Gallery should go back to Venice, the 'Laughing Cavalier' to Hol- land, and all the Turners in the world back to London. This is partly muddled, and partly not so true as it used to be. Histori- cally, the museum as we knew it grew out of the collector's cabinet of curiosities. This naturally enough included many objects intended specifically for collectors, such as Portugal easel paintings by Frans Hals or Giorgione. There is not the slightest reason to return such things to their places of ori- gin, and no one is suggesting it. In some cases they were intended specifically for export.

In the 19th century, museums grew explosively into huge municipal state repos- itories of cultural goods, and all kinds of objects not originally meant for collection were sucked in — altarpieces from sup- pressed religious houses, great chunks of Classical and Mediterranean masonry. Thus not only did the Parthenon marbles end up in London, but the vast Pergamum altar from the Aeolian coast of Turkey in Berlin, large sections of various Pyrennean churches in The Cloisters on the rocky inland tip of Manhattan Island.

This usually involved aesthetic loss. Almost invariably, these things were designed with a specific place in mind. For example, in the case of church paintings, very often the artist would take into account the lighting, the architecture, the setting within the building, and of course the fact that the picture was intended for a place of worship, not a gallery (which is why I think that Bellini would make more sense back in San Giobbe). But, until recently, that loss was usually offset by a gain: more people could see it.

That advantage is rapidly disappearing because of the advent of mass travel. In Lord Elgin's day it was extremely rare and quite dangerous — for a non Greek to visit Athens. Even 35 years ago it was unusual. Now North Europeans annually inundate the place by the million. Cheap jet flights have changed the world, and the way we live, so the museum — fundamen- tally a 19th-century idea — is changing too. Last year I wrote about the Guggenheim, the first imperial museum, which has built an outpost of its New York headquarters in the unglamorous Spanish town of Bilbao (where it is besieged by visitors from Britain among other places). Here we have the steadily proliferating Tate.

The works do not remain motionless as in old-fashioned museums. They constantly shuttle about — so that last autumn it was possible to see the Guggenheim's Mir& on Spanish soil, for the first time ever. It is clear that in the future such mobility will increase, not only within organisations such as the Tate and the Guggenheim, but between museums and countries. The National Gallery in London has had a steady succession of loans from other museums undergoing refurbishment — and highly worthwhile they have been. It is obvious that in the future there will be more and more such arrangements. That is the way museums will go. For certain institutions there would be great advan- tages in pooling collections, and long-term swaps.

In this context we can relax a little about the vexed and often insoluble matter of ownership. In fact Lord Elgin's title to the marbles was much better than some. Plenty of items in the world's great galleries are war loot, pure and simple. Veronese's `Marriage at Cana', one of the Louvre's greatest masterpieces, was pinched by Napoleon from the refectory of the monastery of San Giorgio Maggiore in Venice, and not returned after 1815 because there were worries about taking it back over the Alps (it's very big). Other items in the great museums were dug up under licence from corrupt and indifferent Ottoman officials, or smuggled from their places of origin. Impossible to disentangle all that muddle. In any case, morally, these things belong to the world — or more pre- cisely to anyone who cares about them.

Let's forget about who owns the Elgin Marbles, and lend them to the Greeks for five or ten or 20 years — after all they've been here for nearly two centuries. In return, the Greeks might lend us something nice. It would make a change. All these things should go back, at least for a while — the Pergamum altar to Pergamum, the Luxor obelisk to Luxor (it's absurd to leave it corroding in the middle of a roundabout in central Paris, where a replica would do just as well), the Veronese to San Giorgio. And while they've got the opportunity, per- haps the BM would like to repeat the Luft- waffe's work, and demolish the Duveen Gallery.

Borrowers and lenders be: Elgin Marbles Parthenon Frieze, now in the British Museum

Previous page

Previous page