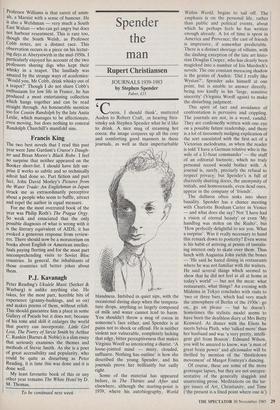

Spender the man

Rupert Christiansen

JOURNALS 1939-1983 by Stephen Spender

Faber, £15

Cocoa, I should think', muttered Auden to Robert Craft, an hearing Stra- vinsky ask Stephen Spender what he'd like to drink. A nice mug of steaming hot cocoa: the image conjures up all the cosy and comforting good manners in these journals, as well as their imperturbable blandness. Imb'bed in quiet sips, with the occasional daring slurp when the tempera- ture drops, anything so largely composed of milk and water cannot lead to harm. You shouldn't throw a mug of cocoa in someone's face either, and Spender is at pains not to shock or offend. He is neither violent nor vulnerable, completely lacking that edgy, bitter perceptiveness that makes Virginia Woolf so intoxicating a diarist. 'A loose-jointed mind — misty, clouded, suffusive. Nothing has outline' is how she described the young Spender, and his journals prove her brilliantly but sadly right.

Some of the material has appeared before, in The Thirties and After and elsewhere, although the starting-point is 1939, where his autobiography, World Within World, begins to tail off. The emphasis is on the personal life, rather than public and political events, about which he perhaps feels he has written enough already. A lot of time is spent in America and Provence; the cast of friends is impressive, if somewhat predictable. There is a distinct shortage of villains, with the dashing exception of the late art histo- rian Douglas Cooper, who has clearly been magicked into a number of Iris Murdoch's novels. The one constant menacing shadow is the genius of Auden: 'Did I really like Wystan?', Spender asks himself at one point, but is unable to answer directly, being too kindly in his 'large, sensitive sincerity' (Virginia Woolf again) to make the disturbing judgment.

This spirit of tact and avoidance of confrontation is pervasive and crippling. The journals are not, in a word, candid. They are confessedly written with one eye on a possible future readership, and there is a lot of tiresomely nudging explication of the sort associated with the first act of a Victorian melodrama, as when the reader is told 'I have a German relative who is the wife of a U-boat commander' — the stuff of an editorial footnote, which no truly personal record would bother with. A journal is, surely, precisely the refusal to respect privacy; but Spender's is full of discreetly shutting doors, the anonymity of initials, and homosexuals, even dead ones, appear in the company of 'friends'.

The dullness often sinks into sheer banality. Spender has a chance meeting with Charlotte Bonham Carter in Venice — and what does she say? Not 'I have had a vision of eternal beauty' or even 'My handbag was stolen on the Rialto', but 'How perfectly delightful to see you. What a surprise'. Was it really necessary to hand this remark down to posterity? Even worse is his habit of arriving at points of tantalis- ing interest only to skate over them. Thus lunch with Augustus John yields the bones — `Fle said he hated dining in restaurants where he was not familiar with the waiters. He said several things which seemed to show that he did not feel at all at home in today's world' — but not the meat: what restaurants, what things? An evening with Mishima in Tokyo concludes with visits to 'two or three bars, which had very much the atmosphere of Berlin of the 1930s': go on, go on please — but he doesn't. Sometimes the stylistic model seems to have been the deathless diary of Mrs Betty Kenward. At dinner with the Eliots he meets Sylvia Plath, who 'talked more' than her husband and was 'a very pretty, intelli- gent girl from Boston'. Edmund Wilson, you will be amazed to know, was 'a man of great brain power' and aficionados will be thrilled by mention of the 'thistledown movement' of Margot Fonteyn's dancing.

Of course, these are some of the more grotesque lapses, but they are not unrepre- sentative of the generally sluggish and unarresting prose. Meditations on the lar- ger issues of Art, Christianity, and Time ('the present is a fixed point where one is') fall flat enough, but more excruciating are the efforts at epigrams or metaphorical encapsulations. Virginia Woolf called the young Spender 'bright eyed, like a giant thrush' which is inspired, as anyone who looks at the excellent photographs here will instantly recognise. But is Germaine Greer illuminated by reference to 'the look of an overgrown schoolgirl who has won all the prizes and has never quite got round to tidying herself up'? Is the soul of America pierced when it is described as 'a country which is entirely different from every other by dint of being more the same'?

Spender accepts with grace that he is only 'a minor poet' and is fond of quoting the line 'All things tempt me from this craft of verse.' The journals are indeed domin- ated more by the picture of the 60-year-old smiling public man (a third of the book is taken up by the years 1974-83) than of someone possessed by his muse, or her desertion of him. In 1980, after a painful accident, he spent three months in hospit- al, where he had thoughts 'of a summing- up kind': Distracted, lazy, pleasure-seeking, frivolous, very ready to fall in with other people's wishes, desiring to please them, fearful of losing their good will. Years wasted, slipping by hour by hour, day by day in a routine of undertakings external to my own inner tasks — reviewing, editing, party-going, travell- ing, attending conferences, UNESCO, En- counter, teaching. Thriftlessness, extrava- gance, folly.

This is extravagantly self-deprecating, inasmuch as the 'routine of undertakings' must add up at many levels to a good and successful life, but on the evidence here Spender is right to incriminate himself for allowing a poetic talent to slide on to the periphery. I'm struggling at the end' he laments, 'to get out of the valley of hectoring youth, journalistic middle age, imposture, money-making, public rela- tions, bad writing, mental confusion.' The way out, as Spender sees it, is up the steep hill of art, but one doesn't find in these journals much sign of the compulsion to make the climb. Worldly honour wins hands down, and as Francis Bacon remarks to Spender on his award of a CBE, 'all this has nothing to do with being an artist'.

Previous page

Previous page