1 4 111 1M R

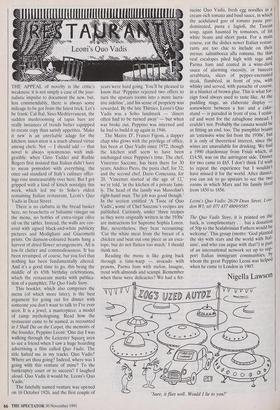

Leoni's Quo Vadis

THE APPEAL of novelty is the critic's weakness: it is not simply a case of the jour- nalistic impulse to document the new, hut, less commendably, there is always some mileage to be got from the latest trick. Let's be frank: Cal-Ital, Sino-Mediterranean, the sudden mushrooming of tapas bars are really instances of trends better equipped to create copy than satisfy appetites. 'Make it new' is an unreliable adage for the kitchen; innovation is a much abused virtue among chefs. Not — I should add — that novel is always synonymous with indi- gestible: when Gino Taddei and Ruthie Rogers first insisted that Italian didn't have to mean pomodori with everything, the once sad standard of Italy's culinary offer- ings rose immeasurably over here. But I got gripped with a kind of kitsch nostalgia this week, which led me to Soho's oldest remaining Italian restaurant, Leoni's Quo Vadis in Dean Street.

There is no ciabatta in the bread basket here, no bruschetta or balsamic vinegar on the menu, no bottles of extra-virgin olive oil on the tables. Instead, the walls are cov- ered with signed black-and-white publicity pictures and Modigliani and Giacometti prints. On damson-coloured beams hang a harvest of dried flower arrangements. All is low-lit clutter and commodiousness. It has been revamped, of course, but you feel that nothing has been fundamentally altered. And it's a good time to go, this being the middle of its 65th birthday celebrations, which the restaurant marks with publica- tion of a pamphlet, The Quo Vadis Story.

This booklet, which also comprises the menu (of which more later), is the best argument for going out for dinner with someone you don't want to talk to I've ever seen. It is a jewel, a masterpiece, a model of camp mythologising. Read how the restaurant came to be named. as recounted in I Shall Die on the Carpet, the memoirs of the founder, Peppino Leoni: 'One day I was walking through the Leicester Squari area to see a friend when I saw a huge hoarding advertising a film called Quo Vadis. The title haltdd me in my tracks. Quo Vadis? Where art thou going? Indeed, where was I going with this venture of mine? To the bankruptcy court or to success? I laughed aloud. Quo Vadis it would be. Leoni's Quo Vadis.'

The fatefully named venture was opened on 16 October 1926, and the first couple of years were hard going. You'll be pleased to know that Peppino rejected two offers to turn the upstairs rooms into a more lucra- tive sideline', and his sense of propriety was rewarded. By the late Thirties, Leoni's Quo Vadis was a Soho landmark — 'diners often had to be turned away' — but when war broke out, Peppino was interned and he had to build it up again in 1946.

The Maitre D', Franco Figoni, a dapper chap who glows with the privilege of office, has been at Quo Vadis since 1972, though the kitchen staff seem to have been unchanged since Peppino's time. The chef, Vincenzo Saccone, has been there for 30 years; Andreo Piero, the pasta chef, for 32; and the second chef, Dario .Comesana, for 20. 'Vincenzo started at the age of 12,' we're told, 'in the kitchen of a private fami- ly. The head of the family was Mussolini's right-hand man. The job was good though.' In the section entitled 'A Taste of Quo Vadis', some of Chef Saccone's recipes are published. Curiously, under 'three recipes as they were originally written in the 1930s' are instructions for Supreme Sophia Loren. But, nevertheless, they bear recounting: `Cut the white meat from the breast of a chicken and beat out one piece as an esca- lope, but do not flatten too much.' I should think not.

Reading the menu is like going back through a time-warp — avocado with prawns, Parma ham with melon, lasagne, trout with almonds and scampi. Remember when these were delicacies? We had a fet- tucine Quo Vadis, fresh egg noodles in a cream-rich tomato and basil sauce, in which the acidulated goo of tomato paste pre- dominated, pasta e fagioli, the Tuscan soup, again haunted by tomatoes, of fat white beans and short pasta. For a main course, eat the dishes newer Italian restau- rants are too chic to include on their menus: saltimbocca alla romana, the thin veal escalopes piled high with sage and Parma ham and coated in a wine-dark sauce of alarming viscosity, or bistecca arrabbiata, slices of pepper-encrusted steak, flambeed, in front of you, . with whisky and served, with panache of course, in a blanket of brown glue. This is what for- eign food always used to taste like. At the pudding stage, an elaborate display somewhere between a hat- and a cake- stand — is paraded in front of you. I resist- ed and went for the zabaglione instead. I couldn't not. Probably the cassata would be as fitting an end, too. The pamphlet boasts an 'extensive wine list from the 1930s', but it is only of theoretical interest, since the wines are unavailable for drinking. We had a 1990 chardonnay from Friuli which, at £14.50, was on the astringent side. Dinner for two came to £65. I don't think I'd wish to repeat the experience but I wouldn't have missed it for the world. After dinner, you can ask to go upstairs to see the two rooms in which Marx and his family lived from 1850 to 1856.

Leoni's Quo Vadis: 26/29 Dean Street, Lon- don W1; tel: 071 437 480919585

The Quo Vadis Story, it is printed on the back, is 'complimentary . . . but a donation of 50p to the Scalabrinian Fathers would be welcome'. This group (motto: 'God planted the sky with stars and the world with Ital- ians', and who can argue with that?)

is part of an international network set up to sup- port Italian immigrant communities, by whom the great Peppino Leoni was helped when he came to London in 1907.

Nigella Lawson

`Sure, it flies well. Would I lie to you?'

Previous page

Previous page