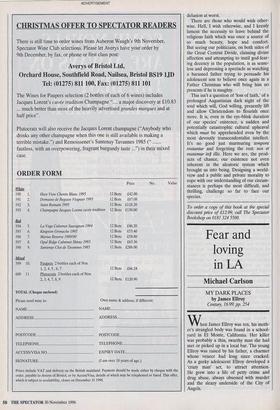

Fear and loving in LA

Michael Carlson

MY DARK PLACES by James Ellroy Cenuay, 16.99, pp. 254 hen James Ellroy was ten, his moth- er's strangled body was found in a school- yard in El Monte, California. Her killer was probably a thin, swarthy man she had met or picked up in a local bar. The young Ellroy was raised by his father, a charmer whose. veneer had long since cracked. As a geeky adolescent Ellroy developed a 'crazy man' act, to attract attention. He grew into a life of petty crime and drug abuse, always obsessed with murder and the sleazy underside of the City of Angels.

As a writer of crime fiction, Ellroy extended the crazy man act into a persona as the 'Demon Dog' of American litera- ture. His novels grew progressively larger in scope, told in a riveting, high-paced prose that reflected a speed-fuelled youth. The Black Dahlia, his breakthrough novel, was based on LA's most famous (until Nicole Simpson) unsolved homicide. It was dedicated to his mother: 'This valediction in blood,' he wrote.

My Dark Places begins with Ellroy's investigations into the death of his mother. He is accompanied by a retired LA County Homicide dick, Bill Stoner. Between the writer and the detective the investigation expands into lives as well as death: his father's, his mother's, and his own.

In conversation, Ellroy's speech mirrors the prose of his novels: fast-paced riffing, seemingly tangential connections, a bebop improv off a well-rehearsed theme. But when he read this book in public a new Ellroy voice emerged: emphatic, steady, factual, almost deadpan. As he listed the details of his mother's killing, he recit- ed the facts of his parents' lives as he knew them: My parents excelled at appearances. They were a great-looking cheap couple, along the lines of Robert Mitchum and Jane Russell in Macao. They stayed together for 15 years. It had to be sex.

He was 17 years her senior. He was tall and built like a light-weight. He was drop-dead handsome, possessed a massive wang. He was an ineffectual man who came off dangerous at first reading. She bought the physical package and the charm that went with it.

But as he and Stoner investigate further, they uncover more of the details of his par- ents' existence which their son had never known. The picture of his father needed lit- tle filling out, but his mother was a shadow, a figure whose existence was defined, for him, by her death. Tracing her life reveals a new person, Geneva Hilleker, a mother a ten-year-old never knew he had. Will people accuse the Demon Dog of going sensitive? 'They'd be mistaken to think that,' laughs Ellroy, but there is a sense of calm in his description of his mother's everyman quality, her lack of consciousness about her life, as if she were ashamed of herself on some deep level, and running and hiding from that shame.

This book is not some form of Psychotherapy. 'Closure is a preposterous concept,' Ellroy says. But it is a book in Which things speak for themselves: a mur- der is not solved, but the facts of four peo- ple's lives are revealed, and for one of them life will never be the same. Ellroy's Portrait of Fifties LA is casually brilliant. His autobiographical venture is moving, Chilling and funny. Ellroy wrote his valediction to his mother ten years ago. This is her benediction; she and her son have reached a measure of peace.

Previous page

Previous page