Cummings and his press

Michael Wynn Jones

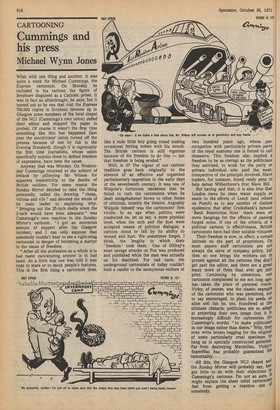

What with one thing and another, it was quite a week for Michael Cummings, the Express cartoonist. On Monday he included in his cartoon the figure of Brezhnev disguised as a Catholic priest. It was in fact an afterthought, he says, but it turned out to be one that cost the Express 700,000 copies in Scotland because up in Glasgow some members of the local chapel of the NUJ (Cummings's own union) defied their editor and stopped the paper in protest. Of course it wasn't the first time something like this has happened (last year the electricians' union turned off the presses because of one by Jak in the Evening Standard), though it is regrettably the first time journalists, whose union specifically enjoins them to defend freedom of expression, have been the cause.

Anyway that was Monday. On Wednesday Cummings returned to the subject of Ireland by pillorying Mr Wilson for apparent insensitivity to the deaths of British soldiers. For some reason the Sunday Mirror decided to take the thing personally, called the drawing "cheap, vicious and vile" and devoted the whole of its main leader to explaining why. "Bringing out the 25-inch shells when the 2-inch would have been adequate" was Cummings's own reaction to the Sunday Mirror's outburst. "I got an enormous amount of support after the Glasgow incident, and I can only suppose that somebody couldn't bear to see a right-wing cartoonist in danger of becoming a martyr in the cause of freedom.

After all the profession as a whole is in bad taste; caricaturing anyone is in bad taste. As a little boy one was told it was rude to stare or to mock people's features. This is the first thing a cartoonist does, like a rude little boy going round making occasional farting noises with his mouth. The British cartoon is still vigorous because of his freedom to do this — but that freedom is being eroded."

Well, is it? The vigour of our cartoon tradition goes back originally to the absence of an effective and organised parliamentary opposition in the early days of the seventeenth century. It was one of Walpole's fortuitous omissions that he failed to curb the cartoonists when he dealt sledgehammer blows to other forms of criticism, notably the theatre. Arguably Walpole himself was the cartoonists' first victim. In an age when politics were conducted on, let us say, a more physical level, when the mob and the duel were accepted means of political dialogue, a cartoon stood or fell by its ability to wound and hurt. We sometimes forget, I think, the lengths to which their ' freedom ' took them. One of Gillray's most savage attacks on Fox was produced and published while the man was actually on his deathbed. For bad taste, the underground cartoonists of today couldn't hold a candle to the anonymous etchers of two hundred years ago, whose preoccupation with particularly private parts of the royal anatomy one is forced to call obsessive. This freedom also implied a freedom to be as corrupt as the politicians they satirized, to work for the party or private individual who paid the most, irrespective of the principle involved. Slave traders, for instance, found ,ready pens to help defeat Wilberforce's first Slave Bill.

But having said that, it is also true that London owes its clean water supply as much to the efforts of Leech (and others on Punch) as to any number of cholera epidemics; that after Cruikshank's famous 'Bank Restriction Note' there were no more hangings for the offence of passing forged notes. If one of the criteria of a political cartoon is effectiveness, British cartoonists have had their notable victories

Their freedom is now, in effect, a certain latitude on the part of proprietors. On most papers staff cartoonists are not always the slave of company policy, but then no one brings the workers out in protest against all the cartoons that don't get past the editor, and there are a great many more of them than ever get into print. Cartooning by committee, one cartoonist complained to me not long ago, has taken the place of personal vision. Vicky, of course, was the classic example of the cartoonist who was permitted, not to say encouraged, to plant his seeds on alien soil but he, too, foundered at the ultimate obstacle; politicians are so adept at projecting their own image that it is increasingly difficult for cartoonists (ir' Cummings's words) "to make politicians in our image rather than theirs." Why, they even write letters begging for the original of some particularly cruel specimen t° hang up in specially constructed gallerieS. Far from destroying Macmillan, Vicky s SuperMac has probably guaranteed /115 immortality. All this, the Glasgow NUJ chapel and the Sunday Mirror will probably say, has got little to do with their objections tc), Cummings's cartoons. I'm not so sure: might explain the sheer relief cartoonists, feel from getting a reaction out 0' somebody.

Previous page

Previous page