Photography

The Art of Photography 1839-1989 (Royal Academy, till 23 December)

A grand celebration

Francis Hodgson

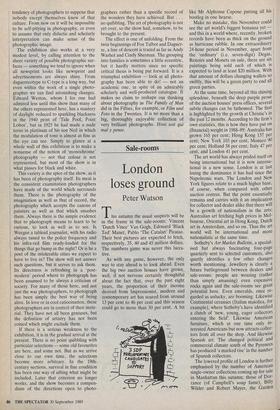

At the end of the Royal Academy's huge exhibition is a joke: Christian Bol- tanski's 'Enfants de Dijon' has dis- appeared. Its caption card is there, at the Man Ray's 'Le Violon d'Ingres', 1924 right height. But the installation itself is up in the dome of the final exhibition room, twinkling and trailing wires among a collec- tion of Burlington House busts, shattering their serene condescension. Photography has climbed in the space of a single exhibition from obscurity to cornice-level, and that was the idea.

This is a great exhibition, and not a moment too soon. Arranged in historical blocks, it shows photography kicking down the doors of the museum in its early stages, and later learning to belong there. The show simply steamrolls any notion that photography might be excluded from the status of art after all these years: by the time we get to the present, any such debate is as meaningless within the show as it has long been outside. Graham Smith's tender images of the pub life in his home town inherit all the artistry of Fox Talbot's scrupulous arrangements, not by some obscure tugging of the curatorial forelock but because photography can do both, easily. By the time we reach Graham Smith, photography can encompass the outsize panels of a Boyd Webb, intended to walk into museums through the acquisi- tions office, as well as the immediate gut-wrenching might of a Don McCullin, which has to kick down those doors in the way photography has always done. Photo- graphy is wide and powerful as a great stream; to set up a great historical show now is a brave thing to do, and the Academy have done it as well as might be expected, better by far than it was possible to fear.

Considering its 500-odd exhibits and its catalogue like a paving-stone, it is not an overbearing show. The selection includes great masterpieces but is not simply a collection of 'Greatest Hits'. Like a good anthology, it tries to show some things which have not been in all the anthologies before, as well as some which simply could not be excluded. So there are plenty of Nadar's extraordinary portraits, but also great stylish inventions by Martin Munkac- si, normally relegated almost to the foot- notes of books on fashion photography. There is one of Edward Weston's peppers, Kertesz's 'Satiric Dancer', a handsome selection of Atget and Sander and Rod- chenko and Julia Margaret Cameron, and many others. Always the light hand of the curators is there, offering a surprise here, a curious juxtaposition there.

If there is a single theme, it is the rather old-fashioned one that photography can include artistry even when its primary intention is not art but something else. No doubt that is so, but in 1989 one hardly needs a major institutional exhibition to prove it. However, the show does not really put forward an argument; it brings to the attention of London's public all the wealth of photographic culture which lies behind the latest advertisement or spread in the glossy magazines — a function which is useful if only because of the recent tendency of photographers to suppose that nobody except themselves knew of that culture. From now on it will be impossible to be self-pitying in photography, or even to assume that only didactic and scholarly interpretation can make sense of the photographic image.

The exhibition also works at a very modest level, by calling attention to the sheer variety of possible photographic sur- faces — something we tend to ignore when all newsprint looks like newsprint and advertisements are always shiny. From daguerreotype to C-type is a long way, but even within the work of a single photo- grapher we can find astonishing changes. Edward Weston, whom I for one had admired less until this show than many of the others represented here, has a mastery of daylight reduced to sparkling blackness in the 1940 print of `Tide Pool, Point Lobos', but in 1925 he had made a nude torso in platinum of his son Neil in which the modulation of tone is almost as fine as the eye can see. Simply to glance at a whole wall of this exhibition is to make a nonsense of the notion of 'monochrome' photography — not that colour is not represented, but most of the show is in what passes for black and white.

This variety is the spice of the show, as it has been of photography itself. Its meat is the consistent examination photographers have made of the world which surrounds them. There is the photography of the imagination as well as that of record, the photography which accepts the canons of painters as well as that which smashes them. Always there is the simple evidence that to photograph means to learn to be curious, to look as well as to see. Is Weegee a tabloid journalist, with his radio always tuned to the police frequency and his infra-red film ready-loaded for the things that go bump in the night? Or is he a poet of the intolerable cities we expect to have to live in? The show will not answer such questions, but it serves to ask them. Its directness is refreshing in a 'post- modern' period where to photograph has been assumed to be always a criticism of society. For many of those here, and not just the war photographers, to photograph has been simply the best way of being alive. In love or in cool ratiocination, these photographers are in control of their mate- rial. They have not all been geniuses, but the definition of artistry has not been coined which might exclude them.

If there is a serious weakness to the exhibition, it is in the gradual arrival at the present. There is no point quibbling with particular selections — some old favourites are here, and some not. But as we arrive close to our own time, the selections become more arbitrary. In the 19th- century sections, survival in fine condition has been one way of sifting what might be included. Later that criterion no longer works, and the show becomes a compen- dium of the directions open to photo- graphers rather than a specific record of the wonders they have achieved. But . . . no quibbling. The art of photography is not yet over., so the show had, somehow, to be brought to the present.

The effect is one of unfolding. From the twin beginnings of Fox Talbot and Daguer- re, a line of descent is traced as far as Andy Warhol and Cindy Sherman. The grouping into families is sometimes a little eccentric, but it hardly matters since no specific critical thesis is being put forward. It is a triumphal exhibition -- look at all photo- graphy has been able to do! — not an academic one, in spite of an admirably scholarly and wel1:produced catalogue. It makes no claim to reshape our thinking about photography as The Family of Man did in the Fifties, for example, or Film and Foto in the Twenties. It is no more than a big, thoroughly enjoyable collection of very brilliant photographs. Honi soft qui mal y pease.

Previous page

Previous page