The remembrance of them is grievous unto us too

John Fowles

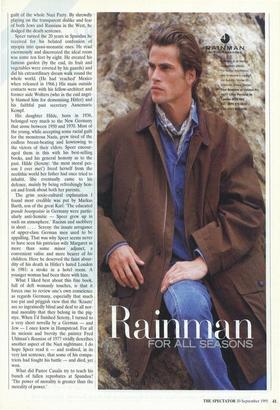

ALBERT SPEER by Gitta Sereny Macmillan, £25, pp. 757 The gadfly perches on the edge of her armchair, quizzing the ox she has cornered. He sits with a faintly hurt look: still as if he can't quite think why this happened to him. The truly excellent photograph — in fact by Don Honeyman, the perceptive gadfly's husband — epitomises the fastidious excel- lence of this formidable and very European book. It gives a shrewdly balanced account not only of Speer and his paradoxes but of much else in Nazi Germany. It is long, thorough and fair, finally dispassionate. The reader is left like Gitta Sereny herself in that defining shot: wondering. Even when, like myself, you suspect the Ameri- can and Russian judges at Nuremburg were right in thinking Speer should have the rope, you still recall the book's subtitle (and its deepest theme): 'His Battle with the Truth.'

Sereny is very good on his long remorse and repentance in Spandau, first provoked by the deeply humane French Calvinist pastor (who hated all 'isms) Georges Casalis. How can anyone, in our waspishly unsettled world, seriously think Speer should have been swept under the bed in

1948? Among other things, we shouldn't have had this soul-searching (both his and ours) biography. Not forgetting — which is not remembering just to seek a sharper edge to revenge — is very profoundly what humanity is about.

Why did this handsome, charming, well- to-do young architect, with his phenomenal memory, his savoir-vivre, his managerial skills, even that unusual thing, a sense of humour (which allowed him to see that most of the rest of the Party — outside the Army — were philistines) give his soul to Hitler? I doubt if the old myth of the froth- ing, carpet-biting maniac, a lie Speer him- self partly helped to propagate in the scramble for plausible scapegoats after the defeat (he later confessed it was false) will survive its much more probable portrait. Hitler's tremendous charisma and over- whelming faith in his own beliefs spread like fish poison along his stream of follow- ers and lieutenants. Sereny thinks Hitler's problem was precisely that he had so many acolytes, yet no real friends. He was totally incapable of personal love.

Speer had the same sad incapacity, and both recognised it in each other. That was the attraction, a shared knowledge of their psychological and spiritual impotence. There is certainly no record at all of any overt homosexual element. Of course, not all Hitler's henchmen were mere steers fo the slaughter-house, as Speer was eventual- ly to half-realise; yet he never completely overcame Hitler's magnetism. That was to be his battle.

One strange episode came near the end. Hitler was deep in the Berlin bunker, Speer had safely escaped to Hamburg. He knew the war was lost; for months he had been disobeying the crazed dictator's demands that the Third Reich be destroyed as pun- ishment for its 'treason' — not loving him as he wanted. But Speer knew a skeleton of Germany must at all costs survive. His plunge back into the Gotterdammerung must have been the single bravest act of his life. How much he revealed to Hitler of what he had been doing, such as saving the Berlin bridges, is not certain, but he must (given the seething mistrust of everyone in that bunker) have known the huge risk he was taking.

The great shadow across Speer's career fell earlier. On 6 October, 1943, there was an important gathering of the top echelons of the party, the Gauleiters and others, at Posen. Late that afternoon Himmler, recently named Interior Minister, issued his Satanic syllogism. Some Jews were pigs; therefore all Jews are pigs; therefore every last man, woman and child of them must be exterminated. (By then there had been rumours for at least a year, through Swedish and other diplomatic channels, of this genocide; both the Vatican and the British were notably deaf to them.) Was Speer there? He claims that he had been so that morning, but had then had to drive to Berchtesgaden to see Hitler, so missed the Himmler speech.

Whether true or not, to pretend that he (then Minister of Arms Production) wouldn't very soon have been told of it by others is not credible. He pretended through the 1948 trial that the gas- chambers had come as a great shock to him: though 'innocent' through ignorance, he would now nobly assume the obvious guilt of the whole Nazi Party. By shrewdly playing on the transparent dislike and fear of both Jews and Russians in the West, he dodged the death sentence.

Speer turned the 20 years in Spandau he received for his belated confession of myopia into quasi-monastic ones. He read enormously and discovered the ideal room was some ten feet by eight. He created his famous garden (by the end, its fruit and vegetables were coveted by his guards) and did his extraordinary dream walk round the whole world. (He had 'reached' Mexico when released in 1966.) His main outside contacts were with his fellow-architect and former aide Wolters (who in the end angri- ly blamed him for demonising Hitler) and his faithful past secretary Annemarie Kempf.

His daughter Hilde, born in 1936, belonged very much to the New Germany that arose between 1950 and 1970. Most of the young, while accepting some racial guilt for the monstrous Nazis, grew tired of the endless breast-beating and kowtowing to the victors of their elders. Speer encour- aged them in this with his best-selling books, and his general honesty as to the past. Hilde (Sereny: 'the most moral per- son I ever met') freed herself from the neolithic world her father had once tried to inhabit. She eventually came to his defence, mainly by being refreshingly hon- est and frank about both her parents.

The grim socio-cultural explanation I found most credible was put by Markus Barth, son of the great Karl: The educated grande bourgeoisie in Germany were partic- ularly anti-Semitic — Speer grew up in such an atmosphere.' Racism and snobbery in short . . . . Sereny: the innate arrogance of upper-class German men used to be appalling. That was why Speer seems never to have seen his patrician wife Margaret as more than some minor adjunct, a convenient valise and mere bearer of his children. Here he deserved the faint absur- dity of his death in Hitler's hated London in 1981: a stroke in a hotel room. A younger woman had been there with him.

What I liked best about this fine book, full of deft womanly touches, is that it forces one to review one's own conscience as regards Germany, especially that much too pat and priggish view that the 'Krauts' are so ingrainedly blind and deaf to all nor- mal morality that they belong in the pig- stye. When I'd finished Sereny, I turned to a very short novella by a German — and Jew — I once knew in Hampstead. For all its meiosis and brevity the painter Fred Uhlman's Reunion of 1977 vividly describes another aspect of the Nazi nightmare. I do hope Speer read it — and realised, in its very last sentence, that some of his compa- triots had fought his battle — and died, yet won.

What did Pastor Casalis try to teach his bunch of fallen reprobates at Spandau? `The power of morality is greater than the morality of power.'

Previous page

Previous page