Exhibitions

Hockney Paints the Stage (Hayward till 29 September)

A talent for transforming

Peter Levi

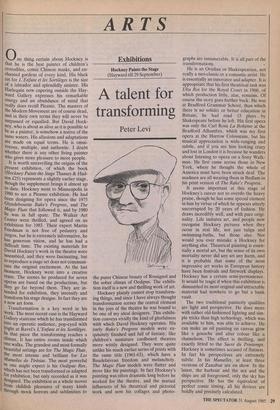

0 ne thing certain about Hockney is that he is the best painter of children's crocodiles, comic Chinese masks, and en- chanted gardens of every kind. His black cat for L'Enfant et les Sortileges is the size of a labrador and splendidly sinister. His Harlequin now capering outside the Hay- ward Gallery expresses his remarkable energy and an abundance of mind that really does recall Picasso. The masters of the Modern Movement are of course dead, and in their own terms they will never be surpassed or equalled. But David Hock- Hey, who is about as alive as it is possible to be as a painter, is somehow a native of the same waters. His allusions and adaptations are made on equal terms. He is omni- vorous, multiple, and authentic. I doubt whether there is any other living painter Who gives more pleasure to more people. It is worth unravelling the origins of the present exhibition, of which the book (Hockney Paints the Stage Thames & Hud- son ,£25) represents a slightly earlier stage, though the supplement brings it almost up to date. Hockney went to Minneapolis in 1980 to see a Picasso exhibition. He had been designing for opera since the 1975 Glyndebourne Rake's Progress, and The Magic Flute that followed it, and by 1980 he was in full spate. The Walker Art Center were thrilled, and agreed on an exhibition for 1983. Their expert Martin F. riedman is not free of pedantry and Jargon, but he is extremely informative, he has generous vision, and he has had a difficult time. The existing materials for David Hockney's work in the theatre were assembled, and they were fascinating, but to reproduce a stage set does not communi- cate the original excitement. At the last Moment, Hockney went into a creative craze. The scenes he produced for seven operas are based on the productions, but they go far beyond them. They are in- tended for exhibition, they intensify and transform his stage designs. In fact they are a new art form.

Transformation is a key word in his Work. The most recent case is the Hayward Gallery staircase which he has transformed into an operatic audience, pop-eyed with fright at Ravel's L'Enfant et les Sortileges. 111 that piece the transforming reaches a Climax. It has entire rooms inside which one walks. The grandest and most formally beautiful settings are for The Magic Flute, the most intense and brilliant for Les Mamelles de Tiresias. The most powerful as one might expect is his Oedipus Rex, which has not been transformed or adapted for exhibition, but only recorded as it was designed. The exhibition as a whole moves from childish pleasures of many kinds through mock horrors and sublimities to the purer Chinese beauty of Rossignol and the sober climax of Oedipus. The exhibi- tion itself is a new and thrilling work of art.

Hockney plainly cannot stop transform- ing things, and since I have always thought transformation scenes the central element in the joys of the theatre he was bound to be one of my ideal designers. This exhibi- tion conveys vividly the kind of gleefulness with which David Hockney operates. His early Rake's Progress models were ex- quisitely finished and full of fantasy, like children's miniature cardboard theatres more wittily designed. They were quite unlike his much earlier series of prints with the same title (1961-63), which have a Baudelairean freedom and melancholy. The Magic Flute models were flatter and more like his paintings. In fact Hockney's painting was often dramatic long before he worked for the theatre, and the mutual influences of his theatrical and pictorial work and now his collages and photo- graphs are innumerable. It is all part of the transformations. • He is an Ovidian or Shakespearian, not really a neo-classic or a romantic artist. He is essentially an innovator and adapter. It is appropriate that his first theatrical task was Ubu Roi for the Royal Court in 1966, of which production little, alas, remains. Of course the story goes further back. He was at Bradford Grammar School, than which there is no solider or better education in Britain; he had read 15 plays by Shakespeare before he left. His first opera was only the Carl Rosa La Boheme at the Bradford Alhambra, which was my first opera at the Harrow Colosseum, but his musical appreciation is wide-ranging and subtle, and if you see him looking crazy and lost in London it is because he wanders about listening to opera on a Sony Walk- man. He first came across those in New York, where he thought the whole of America must have been struck deaf. The madmen are all wearing them in Bedlam in his print version of The Rake's Progress.

It seems important at this stage of Hockney's career not to overdo the heavy praise, though he has some special element in him by virtue of which he appears utterly uncorrupted by 20 years of fashion. He draws incredibly well, and with pure origi- nality. Life imitates art, and people now recognise Hockney pictures when they occur in real life, not just tulips and swimming-baths, but those also. Nor would you ever mistake a Hockney for anything else. Theatrical painting is essen- tially a mortal art, but the sense of its own mortality never did any art any harm, and it is probable that some of the most impressive art works in European history have been festivals and firework displays. Hockney has a certain semi-permanence. It would be tragic if when this exhibition is dismantled its most original and intractable material had nowhere to go but a bank vault.

The two traditional painterly qualities are light and perspective. He does more with rather old-fashioned lighting and sim- ple tricks than high technology, which was available to him, was able to achieve. He can make an oil painting on canvas glow like a gouache and alter colour like a chameleon. The effect is thrilling, and exactly fitted to the Sacre du Printemps. Hockney is sometimes accused of flatness. In fact his perspectives are extremely subtle. In his Mamelles, at least three versions of Zanzibar are on show. In the latest, the harbour and the sea and the ships are all foreground, only the sky has perspective. He has the equivalent of perfect comic timing, all his devices are boldly and precisely calculated.

Previous page

Previous page