THE SMALL INVESTOR

Money to Spare Ralph Harris Finance Companies ... J. W. Huntrods Building Societies ... F. M. Osborn Corporation Mortgages ... . ... Robert Eden The Unit Trusts ... ...P. N. Wise

Money to Spare

By RALPH HARRIS

/TODAY the outlook for the small investor is I better than at any time since the war. For too long the public were invited to 'save for

victory' and then to 'save against inflation' with- out any tangible token of that high regard in which Lord Mackintosh held all patriots who surrendered their cash to the National Savings

Movement. While interest rates hovered around 2+ or 3 per cent., the money saved was falling

in value by 4 or 5 per cent. each year. Consider- ing the combined effects of high taxation, con- tinuous inflation, welfare statism and the tempt- ing array of consumer goods, pessimists should marvel that last year private savings approached anything near the official estimate of £150 million. But now the clouds are lifting. If the imme- diate prospect for tax cuts is somewhat in suspense, Mr. Heathcoat Amory can hardly fail to reform the system in ways welcome to poten- tial savers. If Lord Hailsham is not quite ready to laud self-help above the Welfare State, a fresh motive for thrift has materialised in the form of attractive rates of interest. Above all, we are about to witness the first serious bid for honest money since 1945.

At once fresh problems are posed for investors, especially for those of modest means. Unlike his wealthier counterpart, he does not have a stock- broker and an accountant to help steer his money into the most advantageous channels. Yet there is no substitute for investment advice related to the particular circumstances of each individual.

What is the small investor after? Does he pre- fer steady income to the seductive possibilities of capital gains? In part that will depend on his tax status and his readiness to leave capital in- vested until it can be realised at a profit. Has he

a small nest-egg or inheritance, or does he want to accumulate capital out of income? Has he a definite objective in view, such as saving for school fees or against retirement?

On the answers to all these questions will hang the correct solution of each person's investment problem.

Take first the fellow with a few hundred pounds who deliberately wishes to embark upon the ex- citing path of speculation. If he fancies his luck he could do worse than buy Premium Savings Bonds and trust to Ernie to advance his for- tunes. Alternatively, he may prefer something less dependent on pure chance. If he wants to learn of the mysteries of high finance (and is prepared to pay for his instruction) he may try picking a winner from the equity market.

Although the Stock Exchange is still not adapted to the needs of wage and salary earners

(and Sir John Braithivaite is again reminded that these strange beings dispose of 80 per cent. of net personal incomes in Britain), a request to the Secretary in Throgmorton Street will produce a list of brokers ready to advise the small investor. Without seeking advice, the speculator could off

his own bat plump for steel shares which are dirt cheap for anyone prepared to overlook the risk of another Labour Government hell-bent on renationalisation. At least he will be in good com- pany, since nine-tenths of steel holdings are for less than £500 and two-fifths for no more than £100.

Equities, however, involve risk. During periods of rising prices shares generally move up—hence the 'hedge' against inflation—but some will lag behind. Here is where the unit trust comes into its own. This has been defined as the form of equity investment which enables the investor to open his morning paper without risk of heart attack. It is a method by which the individual delegates his choice of stocks and shares to pro- fessional investment managers, acquiring for every £1 or 10s. unit a packaged portfolio spread over a range of industries and different ranking securities. Although a well-chosen unit beats the market upwards (one unit appreciated threefold between 1947 and 1957) and falls less far on the downturn, all leading units have dropped in value over the past six months. Because of such residual uncertainties, small investors will often steer clear of equities until they have accumulated enough capital to 'play with.'

A way of seeking the fruits of capital appre- ciation without risk is by means of an insurance policy of the 'with profits' variety. Aided by tax concessions (where appropriate) life endowment offers a good bonus when premiums have been completed, with guaranteed life cover in event of prior death. Whether we have turned the tide of inflation, it would seem generally advisable for methodical savers with family responsibilities to get quotations from the leading life offices before probing alternative outlets for savings. And, of course, the younger you start the better the terms. Last year over £150 million of net saving accumulated in the form of individual en- dowment insurance (and almost as much again in group pension schemes) with the eighty life offices.

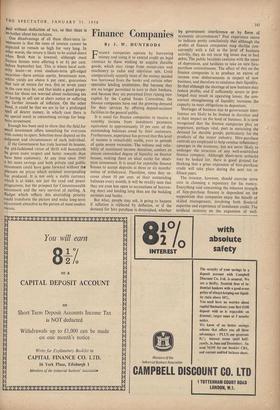

But growing numbers are covered by occupa- tional pension schemes. For them an insurance policy has the disadvantage that in the event of needing to raise the wind a policy has for many years a surrender value well below the total of premiums paid up. A decision about how to invest may, therefore, turn on the time factor. For those not anxious to lock capital up in forms that may only be realised at a loss, the choice comes down to banks, building societies or hire-purchase com- panies. Money on deposit with a bank brings in 5 per cent. and may be withdrawn at a week's notice. Strangely enough this is actually better than the yield on building society deposits and shares for those not liable to tax. Although many building societies exceed the recommended rate of 3} per cent., this is paid net and the tax is not recover-able by sub-standard-rate taxpayers. The great merit of hire-purchase finance houses or 'bankers' is that deposits attract 8 or 81 per cent. and are usually withdrawable on three months' notice. Furthermore, this interest can be Paid without deduction of tax, so that there is no bother about tax reclaims.

One disadvantage of all these short-term in- vestments is that the rates of interest cannot be expected to remain so high for very long. In other words, the return is likely to be scaled down when Bank rate is lowered, although most finance houses were offering 6 or 6f per cent. before September last. This is where local auth- ority loans—or even medium-term gilt-edged securities—have certain merits. Investment now, Whilst yields are above 6 per cent., guarantees that rate of return for two, five or seven years as the case may be, and that looks a good propo- sition for those not worried about reclaiming tax or having to sell out at short notice or suffering the further inroads of inflation. On the other hand, it could be that we are in for a prolonged spell of dearer money, in which case there is no special merit in committing savings for long- term investment.

Enough has been said to show that the field for small investment offers something for everyone with money to spare. Selection must depend on the judgment and circumstances of each individual.

If the Government has truly learned its lessons, the old-fashioned virtue of thrift will henceforth be given more respect and better rewards than have been customary. At any time since 1945 a bit more savings and both private and public investment could have gone forward without the pressure on prices which national overspending has produced. It is not only a stable currency Which is at stake, nor just the road and power programme, but the prospect for Commonwealth investment and the very survival of sterling. A Budget which reflects this overriding priority could transform the picture and make long-term investment attractive to the person of most modest means.

Previous page

Previous page